Font size

Font size

Combating Corruption

Brigadier General, Head of the Directorate of Management & Strategy for Home Affairs, Ministry of Public Order & Citizen Protection.

Corruption is a deeply anti-social behaviour that undermines the democratic institutions, jeopardizes the economic development and the rule of law.

The importance of combating corruption is demonstrated by the fact that a multitude of leading international organizations deal with it, such as the European Union, the Council of Europe, United Nations, the G8, the OECD Financial Action Task Force and INTERPOL.

The phenomenon of corruption refers to large or small countries, to both rich and poor. However, we have to recognize that the results are more catastrophic for the economies of those countries that are underdeveloped or under development.

The real problem of fighting corruption seems to lie, to an extent, in the individuals¢ culture, the administration structure and the application of the relevant laws which refer to prevention, investigation, prosecution and adjudication of corruption cases.

Combating corruption requires:

1. Decision to combat

2. Determination

3. Doctrine of “zero tolerance”

4. Prosecution culture of corruption phenomena, regardless of the typology ("small corruption" [petty corruption] or corruption connected to organized crime)

5. To overcome the culture of concealment

6. Strong legislative framework

7. Harmonization of the legislation of the Countries with the European Union acquis.

8. Strengthening of police and judicial cooperation on the operational level.

9. Information exchange (according to the national legislation) in the field of the combat against corruption through confidence building and networking.

10. Establishment of regular meetings of the Heads of Anti-Corruption Services.

11. Enhancement of the legislative framework and the exchange of information regarding best practices

The main pillars for the fight against corruption, as defined, and by international and Legal Frame, are:

1. Prevention

2. The criminalization of corruption in both public and private sectors.

3. International cooperation

4. The identification and seizure of illegally obtained money and assets

5. The implementation mechanisms, which have to be flexible

6. Transparency

The Internal Affairs of the Hellenic Police, both in terms of prevention, but mainly of repression, as an Enforcement Body of the State to combat traditional and modern forms of corruption (like extreme police behavior, violence, racism), acting according to European Standards, have aligned their strategy under the doctrine of “zero tolerance”, especially in the current socio-economic circumstances.

The Internal Affairs of the Hellenic Police aim for the improvement of services¢ quality for citizens, and also at developing confidence, collaboration and mutuality between police services and citizens, mainly in view of protecting the integrity of the Police and of the Public Sector.

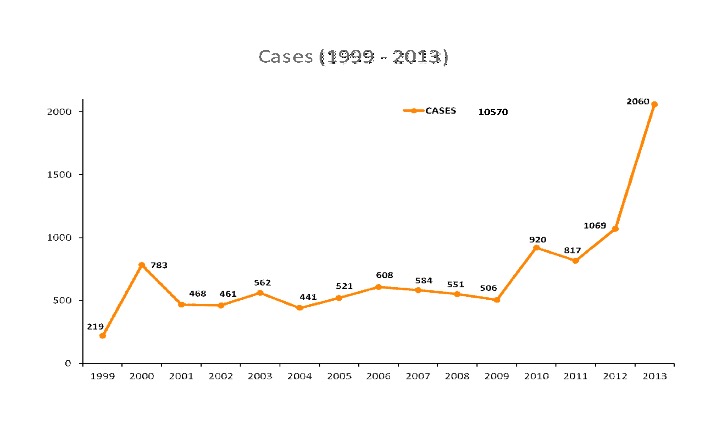

STATISTICS OF CASES HANDLED BY THE INTERNAL AFFAIRS OF HELLENIC POLICE

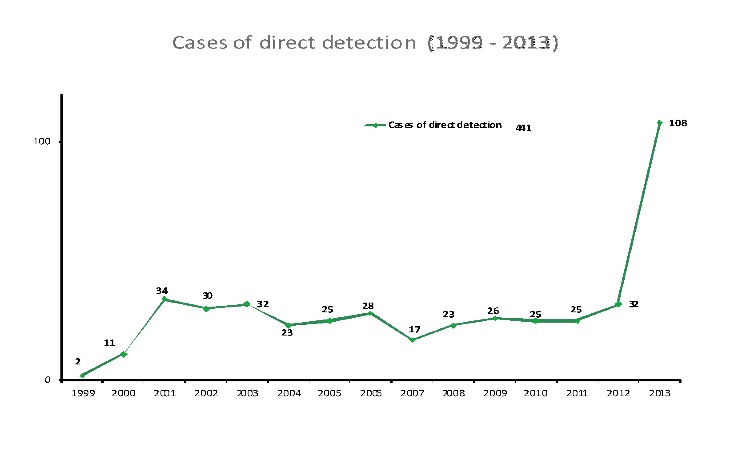

Cases of direct detection (2013)

Cases of direct detection | 108 | Police | 63 |

Public sector | 28 | ||

Both (participation) | 0 | ||

Other | 17 |

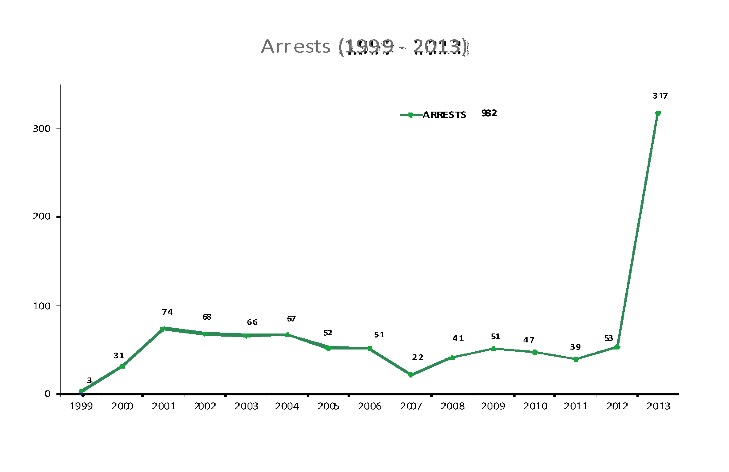

Arrests (2013)

Arrests | 317 | Police officers | 57 |

Special guards | 8 | ||

Employees of P. S. | 41 | ||

Individuals | 211 |

Comparative results (2012 -2013)

· Total cases increased by 86%

· Cases involving police officers increased by 70%

· Cases involving employees of public sector increased by 75%

· Cases of direct detection increased by 248%

· Arrests increased by 522%

· Prosecutions increased by 172%

The relevance of perceptions of corruption to crime prevention in Greece #

Effi Lambropoulou*

1. Introduction

The article refers to the general findings of a research project which examined the relevance of perceptions of corruption to crime prevention in Greece.[1]It also includes the findings of official reports published by various control bodies against corruption in Greece during the last decades, and the results of the European Values Surveys of 1999/2000 and 2008 in order to associate the existing views with facts and hard data.

2. The research

The project began on January 1st 2006 and ended on July 31st 2009 and it consisted of three phases. During the first phase, in order to assess existing conceptualizations of corruption, we studied official documents and during the second phase, we discussed in private and interviewed anonymously various decision-makers: politicians, representatives of public administration, justice, media, police, economy and NGOs. During the third phase we analysed theoretically our findings. The content analysis of texts and interviews was carried out with the software Atlas-ti 5.0.

Specifically, the research team[2] generated, during the first project period (2006), documents from all target groups under examination (see above). It examined, among others, Parliamentary proceedings (2001-2005), reports of the Parliamentary Committee on Institutional Issues and Transparency (2000-2005), electoral programmes of political parties, articles from three daily newspapers of high circulation (2003-2005), legislation and court decisions (1987-2005), NGOs Reports (2000-2005), findings of investigations of General Public Prosecutors (2001, 2002), of party committees (2001) etc.

The project design required selecting at least two case studies, one of which should refer to party financing. Those chosen (two) could generate more data for each target group and caused no serious problems to data collection.

§ Case A – Description. The party financing case study refers to alleged ¡hidden¢ accounts of the right wing party and its President at the beginning of the 1990s.

§ Case B – Description. The second refers to claims of illegal naturalization of foreign nationals - mainly from the former Soviet republics - occurred after the 2000 general elections, under the pretext that they were repatriated Greek Pontians that qualified for such documents.

In the second project period, the research team interviewed representatives of the target groups (22 interviews with 25 persons) in order to assess existing conceptualizations of corruption in Greece and to compare these findings with the results of the previous period.

The content analysis of the documents in the first phase, as well as the interviews in the second, was focused on a) definitions of corruption, b) perceptions of the causes of corruption, c) significance and extension of the problem, d) identification of the victims of corruption, and of the ¡corrupt¢ attributed actors/offenders, and finally e) the perceptions of general anti-corruption legislation (EU and Greek).

As noted previously, in the third phase, we studied national analyses in order to compare them with our findings during the two periods and foreign analyses in order to integrate the two periods¢ findings into a theoretical context.

3. Findings

3.1. Perceptions of corruption according to public discourse (1st Phase)

In the official debate a moral and more or less emotional understanding of the issue prevailed, which is usually either case- or person oriented. The main ¡carriers¢ of the discourse on corruption and its derivatives (¡opacity¢, ¡synchronizing of interests¢, ¡maladministration¢, misgovernment etc.) are Politicians and the Media.

The first consider themselves the main group responsible for corruption control and promotion of transparency in society, while the second promote themselves as guardians of public ethics. Although politicians refer several times to ¡merging of interests¢, ¡corruption¢ etc., when a specific case emerges their debates turn to be mostly party-political. Corruption is referred to mainly as a social illness and occasionally as a social phenomenon of modern societies.

Public administration receives the strongest criticism, as being the basic impediment to transparency and therefore the development of the country; unlike the private economy which is presented as the main ¡victim¢ of corruption.However, Unions¢ representatives of public administration do not participate in the debate, unless their view is not promoted by the media. High ranking civil servants and those who staff control mechanisms associate corruption with maladministration, bureaucracy and non-enforcement of simplification of procedures. They mainly emphasize their efforts for better control of the situation, as does, for example, the Police¢s Division of Internal Affairs.

According to the analysed justice¢s documents, namely, courts¢ decisions, prosecutors¢ findings, articles in legal periodicals etc., all remain adherent to legalese, and ¡corruption¢ did not exist in their vocabulary during the research period (2006-09). The same applies for the Police Division of Internal Affairs.

Media comments on corruption are grounded, in general, and still vague notions about the ¡weak Greek state and the weak public administration¢, resulting in illegal practices. Although they refer to socio-structural and democratic variables, they are unable to give a more sophisticated analysis, thus reproducing mundane theories and trivial comments, around law enforcement and control mechanisms.

For NGOs the issue is ¡a fight¢ and ¡a battle¢ against illegal practices and corruption: ¡the snake¢s egg¢, etc. The term corruption is regarded as given and overused. Their line of argument coincides sometimes with that of the media. They advocate a generalized and synchronized effort of all governments and the involvement of civil society to confront corruption.

Economy¢s documents distinguish between ¡bad¢ state/public sector and ¡good¢ private sector. They regard ¡political-party interests, social class interests and complicated legislation¢ as the main causes of corruption.

The overall conclusion of the first period of research was that according to the texts analysed, the target groups¢ perceptions of corruption in Greece are not considerably different from the corresponding reports of international organisations (TI, OECD, World Bank, etc). This shows the big influence they have.

The policy which is promoted is the strengthening of control mechanisms and severe legislation to prevent the ¡evil¢ and the outbreak of the ¡disease¢.

3.2. Perceptions of corruption according to non-public discourse(2nd Phase)

The interviewees, in general, regard corruption as a global phenomenon, which has always existed in the whole social stratification with different accentuations and forms.

The vast majority of them consider petty corruption in Greece to be prevalent, but when requested to define the specific areas, they referred to public administration and then they specified certain services where much money flows, namely taxation, urban planning, forest protection, garbage and trash policy.

All interviewees from every group strongly denied that their own group has a serious problem, as well as that the whole public sector is corrupt: ¡there are honest and dishonest people everywhere¢.

The transparency of the operation of political parties is regarded as the most serious issue, followed by the role of private economic interests and the media (¡grand corruption¢).

Judges differentiated corruption for legal and illegal activities, and criticised the term ¡corruption¢ as general and inadequate to describe a crime. Even though it is useful for the communication, it is still broad, offering the opportunity for moralising.

The General Inspector of Public Administration underlined that three main factors produce corruption in public administration: its reliance on governments and party politics, money transactions between citizens and public services, and overregulation, complex legislation, as well as ambiguities in legislation (¡grey zone¢) offering high discretionary power to public administration. No real reform will be effective if the involvement of politics in public administration continues.

This view corresponds to some degree with the results of GPO carried out on behalf of public servants¢ Unions (ADEDY) in September 2005, according to which 31.4% of the questioned sample consider that corruption is an issue related to party-loyalties, 30.8% to political leadership, 20.5% to financial and entrepreneurial factors, and 13.6% to civil servants themselves (3.7% gave no answer; total sample 1,200 person over 18 y.o.).[3]

Police ascribed corruption in the corps as ¡occasional¢ and attributed it to the low interest of the leadership (political and natural) in the everyday problems of police officers, but above all its ¡failure to inspire and represent them¢.

The journalists interviewed define the phenomenon as ¡an exchange which is not necessarily monetary and not always illegal¢ (in terms of law). In spite of corruption¢s existence in western societies, what differentiates it from its Greek version is the absence of ¡rules of the game¢.

NGOs¢ regard corruption as ¡social illness¢. According to them, in developed countries corruption emerges only in elites (grand corruption), whereby if it is discovered, it is usually punished, contrary to what occurs in Greece.

Representatives of employers (credit institutes and enterprises) consider the state in general and the Greek state in specific, as significant factors in corruption because it operates against free competition and efficiency.

The representative of the employees has the opposite view. Most Greek companies do not promote competition through innovation and quality, but rely on public procurements. Businessmen advance corruption (paraeconomy and illegal labour force) using every means for maximization of their profit, such as labour cost squeezing and privatizations. For him corruption is the commercialization of democratic values, the dominance of firms¢ profit over human capital.

Regarding the causes of corruption, the approaches mainly followed two lines: an individualistic-ethicist or economist approach, and a sociological approach with either political, or economic and legal accentuation. The historical dimension exists more or less in all views, while argument about the ¡non-enforcement¢ of legislation was hardly mentioned.

a) Corruption reflects low morals and the low quality of a person; corruption is the result of rational choice.

b) Corruption is a product and side effect of economic and political development -- social and financial structures¢, which took place in the post-war era.

According to the interviewees, during the 80¢s the problem in Greece was expanded and took modern forms, while during the 90¢s corrupt practices were established, improved and refined. Corruption is the product of the intensive conflict of interests during the last decades and the ¡widened¢ access to power (not only) in Greece. For some of them corruption is regarded to be a product and reflection of capitalism, while for others it is attributed to overregulation and low quality of legislation.

Concerning the seriousness of corruption, the interviewees do not think that corruption in Greece is higher or much higher than in other countries, but that mass media exaggerate it for reasons of impression and sensation. This causes diffusion among the citizens who in turn accept it as real and true, reproducing and overstating from their side. Yet, it is acknowledged that corruption in modern Greece must be eliminated, because it is incompatible with democratic values and economic growth (¡need for reforms¢).

For some MPs - Justice is unqualified and powerless for investigating ¡strong organised interests¢, so the political and economic system uses it as a means of purification for legitimating their decisions and preferences.

Many interviewees accept that corrupt practices (mainly petty corruption) may operate for the ¡redistribution of wealth¢. Yet it should not be considered real redistribution of resources in favour of the socially disadvantaged and poor population, but as a way through which the middle class exploits a ¡grey zone¢ of the public sector (not defined by the interviewees) with corrupt exchanges and mutual services (bribery, clientelism).

The reliability of CPIs is questioned by all; however, the measurement is not denied or rejected. Perceptions and attitudes are not considered sound tools for measuring corruption; instead statistics and specifically, research in court decisions, decisions of disciplinary councils and of judicial councils bring more valid and reliable data.

The EU¢s assistance in confronting corruption is appreciated, but all consider that EU¢s main interest lies in improving competition in the global economy and controlling the capital of corruption. Yet, in the discourse, the EU¢s role as a prototype for the country¢s improvement and citizens¢ education is declining due to its ¡rapid and big enlargement, which resulted in its worn-out, debunk and heavier bureaucracy¢.

Concerning anti-corruption policies the participants rejected repressive methods and severe punishment and placed emphasis on the strengthening of preventative measures with improvements in the education, information, sensitization, mobilization and awareness of the citizens in order moral standards to be strengthened. Moreover, they insisted on private media control through quality standards (i.e. intensive involvement of the ESR/National Council for Radio and Television for the strengthening of quality standards)− in particular the electronic media, without making concrete suggestions though. They underlined the need for the transparency in public contracts with media owners, for upgrading the role of Journalists¢ code of ethics, as well as of political life, the emancipation of politics from economic interests and the reform of electoral law (voting system); and this contrary to the analyzed documents during the first phase, where more legislation and tough control was implicit (Politics, Justice, Police, Media).

Anti-corruption legislation is regarded as sufficient, but as they underlined, the political determination for reforms and transparency is lacking.

From our research during the second phase it became again obvious that a promotion of views among different social systems operates (Media, Politics, NGOs, and Economy). We also encountered a free interpretation of ¡corruption¢ corresponding to the everyday views of moral/good and immoral/evil. From the discussion we testified that some interviewees exaggerate about several situations to the disadvantage of Greece, comparing them with other countries (i.e. politicians, NGOs), like media and NGOs in the first phase. They frequently described petty corruption as ¡wide-spread¢. However, when requested to provide more information and to provide more concrete evidence, they were obliged to restrict it more and more. This confirms what some interviewees (judges, and NGOs¢ representatives) emphasized about a general tendency of Greek citizens¢ to exaggerate a problem, thus creating a negative image of their country. It is also an outcome of private media¢s overdrawing for their own reasons.

All interviewees omitted from the discussion about corruption the role of justice as a counterbalance to state power and their authority to limit the possible abuses of political power protecting citizens and the public interest. Justice personnel from their side, instead of including independence among the targets which justice has to attain and protect, they content themselves with statements such as, ¡justice is independent¢, ¡untouched by political influences¢ and a ¡fortress of democracy¢.

4. National studies

The increasing number of specialists attempting an analysis of the problem in the national context use more or less political studies having as point of reference the development of democratic governance and the Greek state (e.g. Kontoyiorgis 2005; Thermos 2005),[4] while empirical research is missing.

Political patronage, clientelism and rent seeking are the main topics of the analysts¢ discourse since the 1980s, with some variations, and this concept still prevails. These are followed by the weak civil society and low social capital (Lyrintzis 1984; Sotiropoulos 2007).[5] Many of their standpoints have been expressed by the interviewees (Politics, NGOs, Media).

The rest of the studies refer to elements or activities which the term corruption can or should include, to the existing control systems (e.g. preventive and pre-conventional judicial control), they make suggestions about their legal and organisational improvement, tight laws, explore the role of the specific institutions, such as the Ombudsman and the General Inspector of public administration on fighting corruption etc., or attempt a description of the Greek society on the basis of corruption (Koutsoukis & Sklias 2005).[6]

The majority of both groups of studies consider the term as given, they use it with ease, while only few show some scepticism. Predominantly, they associate corruption with economic and political development. It is actually an (anti-)corruption literature.

5. Facts and numbers

During the last twenty years Greece has employed a robust anticorruption legislation concerning the public as well as the private sector. It has also ratified all the relevant conventions of the European Union (EU), the Council of Europe, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the United Nations (UN), integrating them gradually in the national legislation. In addition, successive laws have been issued for transparency in party financing, and against political corruption. On its own initiative Greece also established several institutions for the prevention and control of corruption in the public services. Examples include:the Police Division [i.e. Service] of Internal Affairs (DEY) in April 1999 with further authority to investigate charges of bribery and extortion of all civil servants; the General Inspector of Public Administration (GIPA) in December 2002; an extension of the Ombudsman¢s responsibilities in January 2003.

However, the more the country improves its normative and administrative instruments to prevent corruption and promote transparency, the lower its score at the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI). In particular, Greece¢s score on the CPI went down from 5.05 to 5.01 in the period from 1988-1996 and plummeted in following years down to 3.8 in 2009. During the economic crisis, the score fell further to 3.4 in 2011 (80th place out of 183 countries), with a slight increase in 2012 to 3.6 (94th place of 174 countries), and in 2013 up to 4.0 (80th place out of 177 countries), the latter being far less than the level of 1996 and in last place as an EU country (TI-CPI 1996-1998; 2003-2013).[7]

The often-used argument by the national experts about the low scores concerns the ¡non enforcement¢ and/or the ¡inefficient¢ implementation of measures and improvements. These scores are not based on empirical research and hard data (e.g., case records, disciplinary decisions), but rather on observed legislative problems.

Justice Statistics show that the number of ¡crimes against duties and service¢ has been for a long time very low; they represent 0.01-0.02 per cent of the total recorded offences after 1980 (NSSG 1980-2012: Table B1) and 0.09-0.12 per cent of the convicted after 1998 (NSSG 1980-2010: Table B4).[8]

Similar are the findings of the various control bodies against corruption. During the period 2004-2012 only a low rate of the 10,323 cases which have been submitted to the General Inspector of Public Administration, referred to corruption. In 2011 they represented 3% of the cases (in total 1,403) and in 2012, 2.1% of the cases (in total 1,499cases) (2012/11: 28, 39; 2013/12: 26-27).[9]

According to the Police Division of Internal Affairs¢ Reports (DEY 2012: 31-36), from 1999 until 2012 the Service dealt with 8,470 cases and brought a charge against 27.8 per cent [2,357] of them. Only a small part of prosecutions represent ¡corruption¢ for police personnel and civil servants too, i.e. bribery [max. 13.4 per cent] and breach of duty, in either the offender¢s or others¢ illegal advantage [2.1-27 per cent/ abs. 38](DEY 2004: 26, Fig. 2; 2010: 29-31, Tables 7, 8; 2012: 27-28, Tables 7, 8).[10]

Other institutions dealing with corruption are the Ombudsman and the Inspectors-Controllers Body for Public Administration [SEEDD]. Both have made few general references to ¡corruption¢ which were maladministration cases (Ombudsman 2010/2011: 91; SEEDD 1998-2005: 4, 8; 2009: 4, 9, 11-13; 2010: 23-4; 2011: 8-9; 2012: 10-11).[11]

Finally, the issuing of Law 4152 [ÉC] in May 2013 is the recent culmination of the Greek government[s] efforts against corruption (Ministry of Justice 2013).[12] The law introduced a National Coordinator on anti-corruption along with a supporting Committee and an Advisory Body. The National Coordinator is directly accountable to the Prime Minister and is Head of 12 competent control services and independent authorities involved.

After all, the view of ¡corrupt¢ public sector is not justifiable by the previous findings. What is more, in the European Values Surveys of 1999/2000 and 2008, over 90 cent of Greeks considered ¡corruption-bribery¢ in the group of highly disapproved behaviours (EVS-Greece 1999, v231; EVS-Greece 2008, v239),[13] over 83 per cent confirmed that citizens must always abide by the law, and over 87 percent criticized behaviours such as ¡cheating on taxes¢ and ¡not paying fare¢ (see also EKKE/NCSR 2003: 29, 57).[14]

Greece¢s very low score on the CPI index, despite its attempts to facilitate transparency, numerous control bodies, few convictions on corruption, high disapproval rate of citizens, and endless criticism from the media (e.g. Eleftherotypia 2007; Lambropoulou et al. 2007)[15] is not easy to explain on first sight. Some studies note that moral disapproval of corruption does not necessarily associate with willingness to make a complaint about it (Killias 1998),[16] or that the followed behaviour [everyday behaviour] does not necessarily coincide with the legitimising of corruption (Karstedt 2003: 389-390, 397-408).[17] This is true, but it is also true that CPI is judged increasingly in terms of economic development (see also Pelagidis 2014).[18] Corruption is treated primarily as a problem of political and economic liberalization and it is taken into consideration for the countries¢ mark in the index of economic freedom (Index of Legal and Political Environment). CPI indicators are constructed by factors not only related to the views of a group of interviewees, mostly businesspeople, about bribery and ¡corruption¢, but also and primarily by the situation of economic freedom and deregulation (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2014: 14-15; see also Sotiropoulos et al. 2011; WEF 2011: 188-189).[19] This explains what the economy¢s representatives said that ¡the best state is no state¢, implying a state better controlled by them, i.e. the free market. It also explains why the established control bodies have very little impact on the country¢s ranking.

6. Conclusions and open questions

From our interviewees and the national studies the main suggestions for confronting the problem may be placed within the dominant conceptualisation of corruption, e.g.controlling overregulation, law enforcement, value change, education etc.

In particular, the importance of education, which is often stressed as a way to transmit desired ethical values to juveniles and further to society, thus discouraging corruption, remains however ambiguous for two reasons. The first one concerns the definition of corruption and the relevant activities by the state and the educational system, along with the ethical system which is adopted. The second reason is related to the strong links between broader social developments and conditions with the educational system and the content of education. As far as competitive neoliberal arrangements in modern societies influence the form and content of education, it is questionable whether corruption (as officially defined and constructed) can be mitigated through the transmission of ¡proper¢ values via education, without social changes (public participation, fair and stable taxation system, professionalism, accountability, transparency etc.) (Kavran & Wyman 2002).[20]

Defining corruption is not an easy task. Every definition of the phenomenon is partial and incomplete, reflecting the legal and socio-cultural context within which the relevant legislation is taking place. It also reflects the agencies and interests that participate in characterising various phenomena as ¡corrupt¢. Thus, corruption is more a social construction than a concrete, universal phenomenon that needs a proper definition in technical terms (e.g. an operational definition). Moreover, it is rather an evolving construction of certain social groups and interests than an act of determining the ¡objective reality¢ of corruption, which leads necessarily to specific policy measures for confronting it. With this I do not support the idea that certain practices such as ¡bribery¢ or ¡political patron-client exchange¢ are a ¡social construct¢ made by dominant interests and rhetoric. Instead I note that the characterisation and labelling of some acts as ¡corrupt¢ serves certain political and economic goals.

The relationship between culture and corruption is more complex than it appears; many scholars follow a line of thought which associates certain cultural traits in developing countries and in countries of the semi-periphery, including Greece, with corruption.

By using corruption as a reference point to analyse a society, we see different things than had we used, for example, social justice, changes in power or in market relations, a values crisis or globalisation. Consequently, a different diagnosis implies a different treatment.

The Greek social system with its subsystems has been researched by several native specialists, i.e. sociologists, political scientists, and media analysts, on the basis of differences and not on similarities with other developed countries in Western Europe, even though clientelist relationships exist to some degree and in various forms in all modern societies (Piattoni 2001).[21] Contemporary developments have rarely been taken into account. Most studies begin with the peculiarities under which the Modern Greek state was formed after liberation from the Ottoman occupation – a starting point that shapes the outcome of the examination.

Corruption is neither an issue of morals nor of embedded attitudes; successful anti-corruption strategies must involve much more besides. It is the result of serious social or organisational problems, for which there does not exist ¡a solution¢.

From all the above, several issues arise for a systematic analysis being also important for an effective policy design in the area. It remains to be proved whether social, political and economic reforms in the context of good governance, as the majority of our discussants noticed, can overturn the state of balance based on ¡corrupt practices¢ in Greece. How important are informal structures and social networks when implementing reforms? What are the roles played by international organisations and multinational companies, in fostering as well as combating corruption?

Such an approach cannot fit justifications of corruption grounded on national tradition, culture, geographic area, etc., since they seem oversimplified if not reproducing stereotypes and, finally, have no effect.

*PhD, Professor of Criminology at the Sociology Department of Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences, 136 Syngrou.Ave.; GR-11252 Athens.

The article is dedicated to the memory of Dr.Garyfallia Massouri, a dear colleague and friend who left us in January 2014.

[1] Panteion University participated in an EU research study, led by the University of Konstanz/Germany and Prof.Dr. Hans-Georg Soeffner, concerning the construction of corruption in certain European countries:Specific Targeted Research Project: Crime and Culture. The relevance of perceptions of corruption to crime prevention. A comparative cultural study in the EU-accession states Bulgaria and Romania, the EU-candidate states Turkey and Croatia and the EU-states Germany, Greece and United Kingdom. Priority 7- FP6 EUROPEAN COMMISSION-2004 -Citizens-5 (at: http://www.uni-konstanz.de/crimeandculture/crimeandculture.html).

[2]The research was carried out and the results are a common piece of work with my Greek colleagues who participated in the Project, of different composition, different length of time, and on various periods of the research: S. Ageli (MA), E. Bakali (MA, Ministry of Interior and Public Administration), N. Papamanolis (MA, Ministry of Interior and Public Administration), E. Bakirli (MA), Dr.Iosifides (Assistant Prof., Univ. of Aegean), Dr.GaryfalliaMassouri and P. Salihos (MA).

[3] The research is no longer available online.

[4]Kontoyiorgis, G. (2005). ¡Corruption and political system¢, in Koutsoukis&Sklias (eds.), Corruption and scandals, 131-143; Thermos, I. (2005). ¡Electoral systems and political corruption in after war Greece¢, in Koutsoukis&Sklias (eds.),Corruption and scandals, 623-631, see below.

[5]Lyrintzis, Ch. (1984). ¡Political parties in post-junta Greece: A case of bureaucratic clientelism?¢,West European Politics, 7: 99-118; Sotiropoulos, D. (2007). State and Reform in Modern Southern Europe: Greece-Spain-Italy Portugal, Athens: Potamos [in Greek].

[6]Koutsoukis, K. &Sklias, P. (eds.) (2005).Corruption and scandals in public administration and politics, Athens: I. Sideris [in Greek].

[7] TI – CPI/Corruption Perception Index (1996-98; 2003-13) (http://www.transparency.org).

[8]NSSG/National Statistical Service of Greece.Justice Statistics 1980-2012, Athens: National Printing Office (1980-1996), since 1997 only online (http://www.statistics.gr/portal/page/portal/ESYE) [in Greek].

[9] GIPA/General Inspector of Public Administration (July 2012; July 2013). Annual Report(s) 2011, 2012, Athens (http://www.gedd.gr/)[in Greek].

[10]DEY/Police Division of Internal Affairs (2004, 2010, 2012).Annual Reports (all reports at: http://www.astynomia.gr/index.php?option=ozo_content&perform=view&id=49&Itemid=40&lang) [in Greek].

[11] Ombudsman (March 2011). Annual Report 2010, Athens: National Printing Office (all reports at: http://www.synigoros.gr/?i=stp.el.annreports) [in Greek]; SEEDD/Inspectors-Controllers Body for Public Administration (1998-2005, 2006-09, 2010, 2011, 2012). Annual Reports, Ministry of Administrative Reform and E-government (ed.), Athens: National Printing Office (all reports at http://www.seedd.gr/)[in Greek].

[12]Ministry of Justice (2013).National Action Plan against Corruption, Athens (http://www.ministryofjustice.gr/site/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=20z-Lk2__sw%3d&tabid=253) [in Greek].

[13]EVS (2010).European Values Study 2008 – Greece, GESIS Data Archive, Cologne, ZA4776, Data file Version 2.0.0, DOI:10.4232/1.10148; EVS (2012). European Values Study 1999 – Greece, GESIS Data Archive, Cologne, ZA3801, Data file Version 3.0.1, DOI:10.4232/1.11536.

[14]EKKE/NCSR (National Centre for Social Research) (2003).Greece-Europe: Society, Politics, Values (http://www.ekke.gr/ess/ess_results.doc) [in Greek].

[15]Eleftherotypia (7 February 2007). ¡Greece: European champion in corruption and bag-snatching¢, by K. Moschonas, (Greek newspaper; the article is no longer available online); Lambropoulou, E., Ageli, S., Papamanolis, N. &Bakali, E. (2007). The construction of corruption in Greece. A normative or cultural issue?,Discussion Paper Series No 6, Konstanz (http://www.uni-konstanz.de/crimeandculture/papers.htm).

[16]Killias, M. (1998) ¡Korruption: Vive la Repression! – Oder was sonst? Zur Blindheit der Kriminalpolitik für Ursachen und Nuancen¢, in H.-D. Schwind, E. Kube & H.-H. Kühne (eds.),Festschrift für Hans Joachim Schneider zum 70. Geburtstag, Berlin, New York: de Gruyter, 239-254.

[17]Karstedt, S. (2003). ¡Macht, Ungleichheit und Korruption: Strukturelle und kulturelle Determinanten im internationalen Vergleich¢, in D. Oberwittler& S. Karstedt (eds.), Soziologie der Kriminalität,KZfSS Sonderheft 43, Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 384-412.

[18]Pelagidis, Th. (2014). ¡Policies against corruption¢, in M. Massourakis and Ch.V. Ghortsos (eds.),Competitiveness and Development, Athens: EET/Hellenic Bank Union, 575-588 [in Greek].

[19] Bertelsmann Stiftung (2014). Policy performance and governance capacities in the OECD and EU, Sustainable Governance Indicators 2014, Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung (http://www.sgi-network.org/docs/2014/basics/SGI2014_Overview.pdf); Sotiropoulos, D.A., Featherstone, K. &Colino, C. (2011). Sustainable Governance Indicators 2011, Greece Report, Bertelsmann Stiftung (http://www.sgi-network.org/pdf/SGI11_Greece.pdf); WEF – Schwab, K. (2011).The Global Competitiveness Report 2011-2012, Geneva, Switzerland: WEF (http://www.weforum.org/reports/global-competitiveness-report-2011-2012).

[20]Kavran, D. & Wyman, S.M. (2002). Ethics or corruption?Building a landscape for ethics training in South-Eastern Europe, New York: United Nations Public Administration Network (http://unpan1.un.org/intradoc/groups/public/documents/untc/unpan003965.pdf).

[21]Piattoni, S. (2001).Clientelism, interests, and democratic representation: The European experience in historical and comparative perspective, Cambridge/ UK et al.: Cambridge University Press.