Thoughts about photographic truth and artistic creation

"The illusion of a literal description of a piece of time and space." This is the definition of photography by the noted American photographer Garry Winogrand. The photograph (merely) describes and can neither narrate nor interpret. What it describes is nothing more than a minimal amount of space and time. However, to this description there are added, the information related to what is portrayed which is already carried in the mind of the viewer of the photograph, as well as those which may be derived from an accompanying text. And then automatically all this external and - above all - non-visual information is attributed to the photo itself, giving it a quasi-evidentiary character, i.e. the character of a record of fact. In a nutshell, everyone is expecting a photo to "tell" things that they have in their mind while a photo cannot "say" anything but only insinuate things that concern the photographer and reference things that concern the viewer.

The two most popular and widespread types of photography (commemorative /memento photography and journalistic photography) are fed by the presence of faces /persons and events that have preceded the photograph. Therefore, the truth of these photographs is perceived either a given or provable. In these cases, a photograph usually acts as an emotional complement of words or of previous information. The digital photographic technology with the deformation capability it offers has come to set free the photographic image from the burden of a half-truth and of partly complete evidencing.

The free field of expression and creation that belongs exclusively to photography (and not to factual information it encompasses) could be characterized as its artistic dimension. Such photograph cannot (it too) but accurately describe a piece of space and time, but it is called upon to take advantage of the information and knowledge the photographer has and transfer them to the viewer, not though as a direct and straight reference, but rather as an indirect footnote to them. Photographic discourse, like any artistic discourse, cannot be proof of fact, but rather poetic and metaphorical. The emotional response caused by a particular face (commemorative / memento photography) and the surprise caused by a particular event (journalistic photography) must attain to become reference points in order to generate emotional responses through the very photographic event and not from what it only partially can portray. Thus, the depiction of a woman and a child does not prove a familial or emotional relationship, but it may reference to it. And a twitching of a face from a possible laughing outbreak may make a reference to a scream or heartbreaking crying. The photographer neither can nor should avoid the exact description, since this is the reason for the existence of a photograph, but the photographer's choice of time and space will be based on what he has excluded on his own initiative from the photograph, that is, the existence of the four sides of the photo, in other words the "frame", which ultimately gives meaning to the little information enclosed in it. The more impressive, striking, specific and recognizable the information is, the harder it is for the photographer to be able to elicit an emotional response and generate interest by referring and not by showing.

As a result, it is extremely rare for a photo to be related to committing a crime and to generate interest merely by reference to it. First of all, because the acts (preparatory or executory) of a crime require the ability not of simple description, but of narrative (even fiction), that is something which is the property and in the facilities of cinematography and literature, or the ability of transformation and, possibly, of idealization, which is a realm of painting art. Secondly, the consciousness that the photographic description constitutes a silent and conventional acceptance of the "truth" it depicts, it ends up to either making us fully believe the truth of the depicted (which can only be done by invoking extra-photographic information) or not to believe the truthfulness of the description and to lose the photographer’s "truth", that is to say his creative presence.

The discourse about photography seems (and it is reasonable) to be constantly craving for photographic examples. Again, these examples are in danger of oversimplifying the complexity of the problems and the highly complex role that photography plays in the culture of our century as a memory or as documentation, but also in parallel as a source of emotion and a point of reference.

- Photo 1

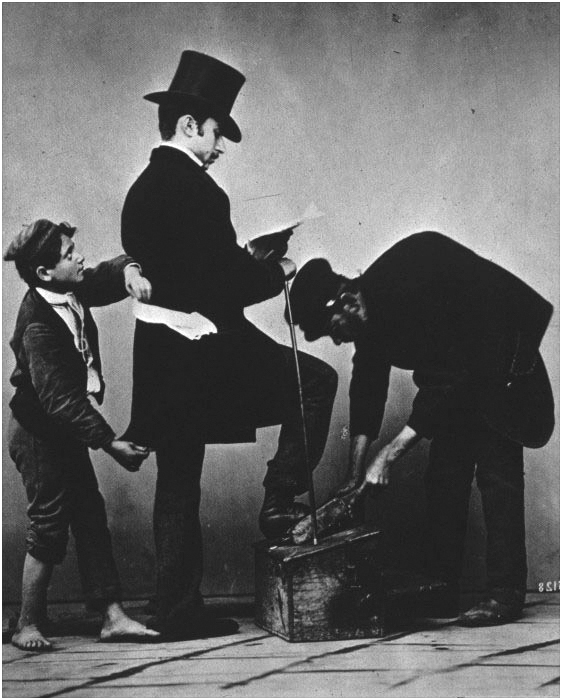

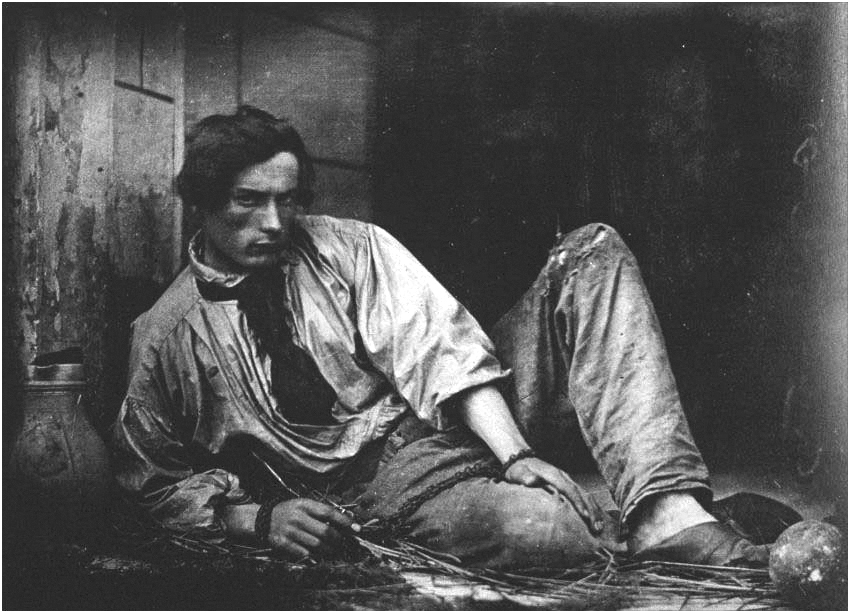

- Photo 2

However, let's try to apposition some photos to make more perceivable the preceding questions and comments. In one of the first photographs of the century before last (taken through a large wooden machine and a glass photo plate), an unknown to us photographer depicts the picking by a young thief of the wallet of a gentleman who is having his shoes polished (Photo 1). The knowledge that we have convinces us that the scene is staged, so our interest is not related to the event or to photograph but (possibly) to the history of the Photography in general. In another photo of the same era, also by an unknown photographer (Photo 2), a handsome and calm young man is pictured with an iron ball on his leg /ankle. Here a caption informs us that this is an actual prisoner. In this case, we are more willing to believe the claim, but again we realize that the truth of the information comes from the caption, since it could be as fictitious as the previous one. Again, we remain indifferent both to the photo (which did not transcend the fact) as well as to the very fact (which did not convince us of its importance).

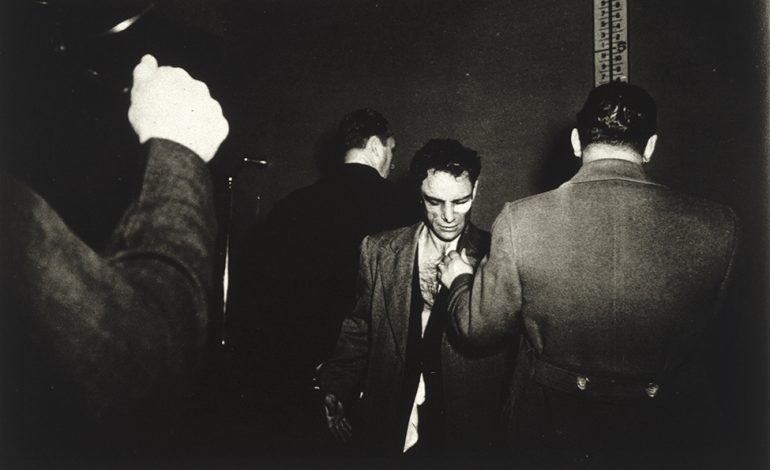

- Photo 3

If at that time (19th century) the curiosity of the public about the new "toy" ensured the success of the photographer, in the late 20th century, the cunning photographers of conceptual art had to conjure up something seemingly more complex. The cinema seat depicted by the American Fine Art Photographer (!) Joel Sternfeld (born in 1944) is of no interest (photographic or otherwise) and the photographer knows this very well, so with the wordy accompanying caption, he informs us that this is the seat where Lee Harvey Oswald sat when he was arrested by Dallas police for the murder of President Kennedy. The caption also tells us the date and time of the arrest, as well as the titles of the double-bill films screened on that day at that movie theater. He attempts thus to pump up interest (because an artistic or other emotional response is unattainable, nor is he even pursuing it) by remolding into an artistic find/innovation what perhaps in the 19th century constituted (even maybe a simple) surprise and curiosity. Furthermore, in order to achieve the reshaping of the simplistic find into an instrument of artistic avant-garde and not to be treated as a mere naive journalistic effect, he repeats the same novelty with other consciously indifferent photographs with correspondingly extensive captions. Two points deserve to be emphasized, firstly, that the photographs should not seek autonomy and any special value in this regard because the novelty will be undone and secondly that no one is allowed to attempt something like this after him because it will cease to be a novelty. This is also the well-known déjà vu (always in French and preferably with an English accent) used internationally by gallerists.

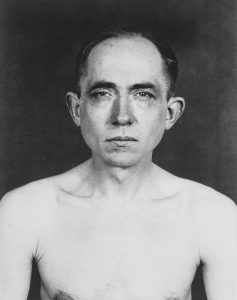

- Photo 4

- Photo 5

- Photo 6

- Photo 7

Negative examples may be more helpful to support opinions, but they deprive us of the joy and enjoyment of art. So let's transport ourselves to the interwar years, in a German small-town, where the notable photographer August Sander (1876-1964) began, as a personal photographic endeavor (that we would call today a project), to photograph his fellow citizens without wanting to use these photographs for any purpose, scientific or professional. At the bottom (or on the flipside) of each photo he made sure to simply note down the capacity of the person being photographed. The diverse capacities have no purpose (nor could they) interpret or supplement the photographs, since (according to what we said above) they could be either fictitious, random or imaginative. A half-naked man having no expression we are informed that (?) he is a political prisoner (Photo 4). Placing next to it the photograph of a Wehrmacht soldier (Photo 5) could make the information dimension of the previous photograph even more dramatic. Although the soldier's expression, as well as the particular rural background of photography, give rise to more questions than answers. The subsequent apposition (Photos 6 and 7) of a beggar and a woman, who, as we are informed, is the victim of an explosion, causes even more questions. Tackling all of these photographs together shows how much free they are from their minimalist captions and how equally freed they are from the truth of the information that accompanies them. Here the photographer created his own shadow-theater, his own world, his own truth.

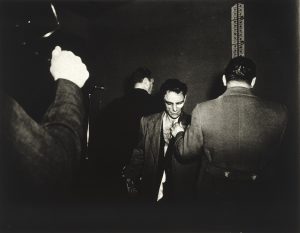

- Photo 8

- Photo 9

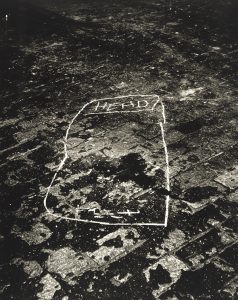

- Photo 10

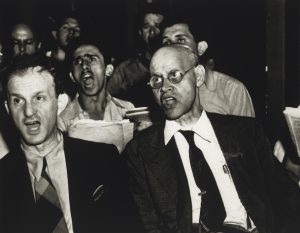

- Photo 11

If, despite all the previous, I had to come up with a photographer that is related to the world of crime (so I would be slightly consistent with the request for writing this article), I could not find a better example than the American (of Austrian origin) Arthur Fellig (1899-1968), best known by the pseudonym Weegee, which he himself had attributed to himself as a wondrous exclamation. In order to survive professionally, he had made acquaintances with police officers and firefighters, so that he was summoned immediately after a crime was committed. Here, the truth of what is depicted is almost self-evident. No captions needed. However, the truth ends up weaker than the description. And this constitutes the power of the photograph, or better yet the originality of the photographer who knows how to take advantage of the power of a photograph to ultimately transcend (in his really good pictures) the fact that he depicts. The stern frame and distorting and selective illumination with strong flash lighting, whose angle does not correspond to the angle of reception, give the feel of a theatrical stage scene (Photos 8 and 9). While the depiction of a body outline (Photo 10) makes the photograph much more powerful than the potential depiction of this corpse, since it emphasizes the dimension of the photograph as a trace, making the outline of a possible body stronger than the presence of a real (with a question mark always) cadaver.

It is worthwhile to emphasize the importance of Weegee's very good photo which portrays a crowd that screams (Photo 11). It is a photo that illustrates with incredible intelligence the transformative power of the photographic medium and makes indifferent (but not at all useless) the reality behind the picture. This photo is part of a larger photographic project by Weegee, who photographed choirs. These men, therefore, have no value as chorists (which they are), or as protesting citizens, or as a dangerous manipulated crowd, simply because the photograph must - without ignoring the fact which it describes - transcend it into an outline trace, so as to enlarge its significance and link it to the outline traces of other photographs of the same photographer. If the diligent reader goes into the trouble to appose the body outline, the prisoners in the cage and the screaming chorists (Photos 9-10-11), he will realize the photographer's dynamic presence and importance and overlook the subjects (truthfully and accurately outlined) that were depicted. Weegee died without being recognized as a good photographer, but rather as a photojournalist known during his time.

![Hang ’Em High (1968) [Κρεμάστε τους ψηλά] <br/>Αυστηρότητα και επιείκεια ως στοιχεία <br/>της θετικής γενικής πρόληψης](https://theartofcrime.gr/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/morozinis_cover_nov21-237x143.jpg)