I. Introductory remarks

Defying precisely cybercrime is not an easy task. Firstly, a distinction between cybercrime and computer-related crimes should be provided. Cybercrime in a narrow sense is described as any illegal activity in which electronic operations (computers or networks) are a tool, a target or a place of criminal activity. On the other hand computer-related crimes (cybercrime in a broader sense) includes an illegal activity committed by means of, or in relation to, a computer system or network. The board definition encounters difficulties as it is questioned, whether, for example, it includes the case where the offender used a laptop to hit the head of the victim resulting in his death[1].

The Council of Europe Convention on Cybercrime[2] distinguishes between four different types of offences: a. offences against the confidentiality, integrity and availability of computer data and systems b. computer-related offences c. content-related offences and d. offences related to infringements of copyright and related rights.

The right of proof has the meaning that even questionable means of evidence cannot be excluded and there should be no restrictions regarding the evidence material[3]. In that direction, elecrtronic evidence -although its acceptance is sometimes controversial- is the most efficient way of identifying the digital prints of cybercrime.

II. Types of cybercrime

The first type of cybercrime includes illegal access such as ‘hacking’ which is an unlawful access to a computer system. Hacking into a computer system and modifying information on the website can be prosecuted as illegal access and data interference.[4] This includes also the term «hacktivism» which combines the words hack and activism and describes hacking activities performed to promote an ideology[5]. Offenders use this access to commit further crimes, such as illegal data acquisition (data espionage), data manipulation or denial-of-service (Dos) attacks. These attacks are launched to take down a website by flooding it with fake traffic[6].

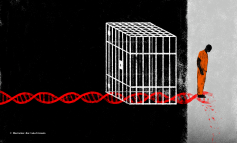

Computer-related offences include computer-related fraud[7], computer-related forgery[8], phishing, identity theft and misuse. The most common fraud offence include online auction fraud. Offenders committing crimes over auction platforms can exploit the absence of face-to-face contact between sellers and buyers. A common method includes offering non-existing goods for sale and requesting buyers to pay prior to delivery. Computer-related forgery refers to the manipulation of digital documents. The falsification of e-mails is an essential element of ‘phishing’ which seeks to make victims disclose personal/secret information. The term ‘identity theft’ is described as the criminal act of fraudulently obtaining and using another person’s identity. That offence contains the use of malicious software or phishing attacks in order the offender to obtain identity-related information, which enables the perpetrator to commit further crimes, i.e. credit-card fraud[9].

The category of content-related offences covers illegal content including child pornography[10], xenophobic material or insults related to religious symbols, racism, hate speech or glorification of violence. The appropriate development of legal instruments to deal with this category is influenced by national approaches which take into account fundamental cultural and legal principles. For example the dissemination of xenophobic material is illegal in many European countries but can be protected by the principle of freedom of speech in the USA. Furthermore, there is lately a rise in the number of websites promoting racist content and hate speech. It should be noted here again that not all countries criminalize these offences, as in many countries, such content may be protected by principles of freedom of speech. Illegal gambling and online games fall also under this category of cybercrime. Online casinos are available which can be used in money-laundering and activities financing illegal acts. Furthermore, the demand for anonymous payments has led to the development of virtual payment systems and virtual currencies, such as bitcoin and another cryptocurrencies[11]. It is considered that four primary areas of criminal activity lend themselves to cryptocurrency: tax evasion, money laundering, contraband transactions, and extortion[12].

The broader definition of cybercrime includes also copyright and trademark related offences. Companies distributing their products directly over the Internet face problems involving copyright violations, as their products may be downloaded and distributed. Specifically, digitization has led to new copyright violations as it is very easy to duplicate digital sources without loss of quality and as a result to make copies from any copy. Although protection technologies are advanced, offenders succeed in falsifying the hardware used as access control or have broken the encryption using software tools. Criminalization of copyright violations does not focus only on file-sharing systems but further on the production, sale and possession of illegal devices or tools that enable the users to carry out copyright violations[13].

Trademark violations include the use of trademarks in criminal activities with the aim of misleading users, as the good reputation of a company is linked with its trademarks. Offenders use brand names and trademark fraudulently in a number of activities including phishing, where millions of e-mails are sent out to Internet users resembling e-mails from well-known companies including trademarks. Also domain name related offences are here included. For example cybersquatting which is the illegal process of registering a domain name identical or similar to a trademark of a product or a company. Another example is ‘domain hijacking’ or the registration of domain names that have accidentally lapsed[14].

III. Electronic evidence

Adopting legislative measures enabling the electronic evidence[15] facilitates the detection, investigation and prosecution of cybercrime. There are three types of evidence that might be needed in legal proceedings: a. Evidence from publicly available websites, such as blog postings and images uploaded to social networking websites. b. The substantive evidence that is the e-mail or documents in digital format that are not made publicly available and which are held on a server. c. Purported user identity and traffic data (meta data) that is used to help identify a person ‘s finding out the source of the communication, but not the content[16]. Electronic evidence (also referred to as digital evidence) may take form of text, video, photos or sounds[17]. Data may originate from carriers or access methods, such as mobile phones, webpages, on-board computers or GPS recorders, including data stored in a storage space outside the party’s own control. Electronic message (e-mail) is a typical example of electronic evidence, as it is evidence originating from an electronic device (computer or computer like-device) and includes metadata. Metadata means data about other data and it can be referred to as the digital fingerprint of electronic evidence. It may include evidentiary data, such as the date and time of creation or modification of a file or document, or the author and the date and time of sending the data.

Electronic evidence should be neither discriminated against nor privileged over other types of evidence and courts should adopt a technologically neutral approach, meaning a technology that enables authenticity, accuracy and integrity of data. The Criminal Code in Italy[18] contains a text in Art. 491 defining an electronic document as any computer tool that contains information with evidentiary value or any software indicated for the processing of this information. In Ireland, section 2 (1) of the Criminal Evidence Act 1992 provides that a document includes: (i) a map, plan, graph, drawing or photograph or (ii) a reproduction in permanent legible form, by a computer or other means (including enlarging), of information in non-legible form. It appears to be three types of equivalence between electronic and traditional evidence. The first refers to that of the electronic document to a paper document, the second type of equivalence is referred to that of the electronic signature with the handwritten signature and finally electronic mail is compared to postal mail. According to Art. 190 of the Criminal Procedural Code of Portugal the interception of electronic mail is compared to a telephone conversation[19].

Collection of electronic evidence in an unlawful way (e.g. obtained by infringing privacy or confidentiality principles or personal data protection) results in its inadmissibility. In some countries such as Germany[20], Ireland and England and Wales evidence obtained by a procedure that is shown to be illegally obtained in some way is not admitted[21]. In Belgian criminal procedure the use of illegally obtained evidence is forbidden[22]. In France, a judge cannot dismiss an item of evidence because it might have been obtained illegally or in an unfair manner, and such evidence must be submitted to cross-examination[23]. However, generally speaking, the circumstances in which interferences by public authorities are permissible should be exceptional, i.e. for reasons of state security, public safety, whistleblowing protection, or the prevention and suppression of criminal offences.

Treatment of electronic evidence should not be disadvantageous to parties to criminal proceedings, such as where the party is deprived of the possibility to challenge the authenticity of evidence or if the court requests a party to submit printouts of electronic evidence that misses important metadata[24]. Metadata provides the necessary context to evaluate the evidence in a similar way as a stamp provides context to evaluation of the paper letter and its content[25]. Electronic evidence include metadata and it can be used to trace and identify the source and destination of a communication, data on the device that generated electronic evidence, the date, time, duration and the type of evidence[26].

Printed electronic evidence can be easily manipulated as it excludes metadata or other hidden data. When the party submits a printout from the web browser screen, such a printout can hardly be recognized as reliable electronic evidence or the basis for the expert’s verification of authenticity. The printout is a copy of the screen display. It can be modified in a very simple manner because no special software or hardware requirements are required for this purpose. In that direction instant copies of computer screen (screenshots) are not to be considered trustworthy. If a copy (paper copy) of electronic evidence is filed, the court may order at the request of a party or on its own initiative, to provide the original of the electronic evidence by the relevant person. An example of evidence that may have significant importance for resolving the point in issue, provided it is presented in original format, is geo location data[27]. Example for the admissibility of such electronic evidence in legal proceedings can be found in the eIDAS Regulation[28], which regulates also trust services. These services provide technological mechanisms that ensure the reliability of evidence. For example certificates to electronic signatures, sometimes referred to as the digital ID of a person, may provide both authenticity[29] and integrity of the data. Where the identity of the signatory with an electronic signature is doubtful, a court may request the service provider related to the electronic signature to make a statement in relation to the matters upon which it is competent to provide evidence. Timestamping (certification of time) may be equally important for evidencing the integrity of an electronic data. Timestamp is a mechanism that allows to prove the integrity of data. It demonstrates that data existed in a specific moment and have not been modified. The timestamp provides a value to the electronic evidence, as it includes relevant metadata about the moment of its creation.

Blockchain is an example of technology that is specifically used for securing the evidence. It is an emerging technology, which has potential to provide increased trust and security in electronic evidence[30]. Blockchain technology means a mathematically secured, chronological, and decentralized consensus ledger or database that refers to the list of records (blocks) which are linked and secured using cryptography, whether maintained via Internet interaction, peer-to-peer network, or otherwise. By design, a blockchain is inherently resistant to modification of the data. Once recorded, the data in any given block cannot be altered retroactively without the alteration of all subsequent blocks, which requires collusion of the network majority. This makes blockchain suitable for the evidencing purposes.[31] Since cryptocurrencies are based on the blockchain technology offences regarding them could be traced by using it for evidencing reasons[32].

Digital evidence plays an important role in various phases of cybercrime investigations[33]. It is in general possible to divide between two phases: the investigation phase (identification of relevant evidence, collection and preservation of evidence, analysis of computer technology and digital evidence) and the presentation and use of evidence in court proceedings. The first phase is linked to computer forensics, which describes the systematic analysis of IT equipment with the purpose of searching for digital evidence[34]. Computer forensics include investigations such as analyzing the hardware and software used by a suspect, recovering deleted files, decrypting files or identifying Internet users by analyzing traffic data[35]. The second phase relates to the presentation of digital evidence in court[36] and it is closely linked to specific procedures that are required because digital information can only be made visible when printed out or displayed with the use of computer technology[37].

Depending to the ICT and the Internet services used by a suspect, a wide variety of digital traces are left. If a suspect uses search engines[38] to find online child pornography, then IP-addresses and in additional identity-related information (such as Google ID) are recorded. Digital cameras used to produce child pornography images in some cases include geoinformation in the file that enables investigators to identify the location where the picture was taken if such images are seized on a server. Suspects who download illegal content from file-sharing networks can in some cases be traced by the unique ID that is generated in the installation of the file-sharing software. And the falsification of an electronic document might generate metadata that enable the original author of the document to prove the manipulation[39].

The need to deal with digital evidence raises challenges in terms of the layer of abstraction and the fact that digital evidence cannot be presented without tools like printers or screens, has implications for the design of courtrooms. Screens need to be installed to ensure that the judges, prosecutor, defence lawyers the accused and of course the jury are able to follow the preservation of evidence. Installing and maintaining such equipment generates significant cost for judicial systems[40].

Security Union: Facilitating access to electronic evidence

Today much of the useful information needed for criminal investigations and prosecutions is stored in the cloud, on a server in another country and/or held by service providers that are located in other countries[41]. The current EU legal framework consists of Union cooperation instruments in criminal matters, such as the Directive 2014/41/EU regarding the European Investigation Order in criminal matters[42], the Convention on Mutual Assistance in Criminal Matters between the Member States of the European Union[43], Council Decision 2002/187/JHA setting up Eurojust[44], Regulation (EU) 2016/794 on Europol[45], Council Framework Decision 2002/465/JHA on joint investigation teams[46], as well as bilateral agreements between the Union and non-EU countries, such as the Agreement on Mutual Legal Assistance (‘MLA’) between the EU and the US[47].

The European Commission has proposed legislation to facilitate and accelerate law enforcement and judicial authorities’ access to electronic evidence to better fight crime and terrorism[48]. This will give authorities the right tools to investigate and prosecute crimes in the digital age. The proposed new rules would provide a faster tool for obtaining electronic evidence. The European Investigation Order (EIO) and the Mutual Legal Assistance (MLA) will continue to exist, but there would be a fast track alternative for the specific case of electronic evidence: the European Production Order. The new EU rules will allow the judicial authority to go directly to the legal representative of the service provider in another EU country[49]. Also the evidence will no longer travel back through many hands, but go directly from the legal representative to the authority requesting the data. The proposed new rules also include a European Preservation Order which may be issued to avoid deletion of electronic evidence. By introducing European Production Orders and European Preservation Orders, the proposal makes it easier to secure and gather electronic evidence for criminal proceedings stored or held by service providers in another jurisdiction.

Such Orders may also be issued for specific harmonized offences listed in the provision for which evidence will typically be available mostly only in electronic form. The offences are specific provisions of: (i) Council Framework Decision 2001/413/JHA combating fraud and counterfeiting of non-cash means of payment[50], (ii) Directive 2011/93/EU on combating the sexual abuse and sexual exploitation of children and child pornography and replacing Council Framework Decision 2004/68/JHA[51] and (iii) Directive 2013/40/EU on attacks against information systems and replacing Council Framework Decision 2005/222/JHA[52]. Orders may also be issued for offences listed in Directive 2017/541/EU on combatting terrorism and replacing Council Framework Decision 2002/475/JHA and amending Council Decision 2005/671/JHA[53].

NOTES

[1] See ITU publication “Understanding cybercrime: phenomena, challenges and legal response” prepared by Prof. Dr. Marco Gercke, p 12 f. available online at: www.itu.int/ITU-D/cyb/cybersecurity/legislation.html.

[2] Council of Europe Convention on Cybercrime (CETS No. 185) available at: http://conventions.coe.int.

[3] See Georgios Orfanidis, Die vorweggennomene Beweiswürdigung im Zivilprozess, in Festschrift für Hanns Prütting zum 70. Geburtstag, Carl Heymanss Verlag, 2018, 455, 456.

[4] Recently, on 28th September 2018 Facebook announced it was hacked and almost 50 million users have been affected. A hacker gained access to nearly 50 million Facebook user accounts by exploiting a weakness in the social network’s systems, see https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/28/technology/facebook-hack-data-breach.html.

[5] Modern hacktivism, has been defined mainly by the group known as 'Anonymous' see http://www.itpro.co.uk/hacking/30203/what-is-hacktivism.

[6] Ibid.

[7] According to Art. 8 of the Europe Convention on Cybercrime computer related fraud is described as: “when committed intentionally and without right, the causing of a loss of property to another person by: a. any input, alteration, deletion or suppression of computer data, b. any interference with the functioning of a computer system, with fraudulent or dishonest intent of procuring, without right, an economic benefit for oneself or for another person”.

[8] According to Art. 7 of the Europe Convention on Cybercrime computer related forgery is defined as follows: “when committed intentionally and without right, the input, alteration, deletion, or suppression of computer data, resulting in inauthentic data with the intent that it be considered or acted upon for legal purposes as if it were authentic, regardless whether or not the data is directly readable and intelligible”.

[9] See ITU publication (n 1) p 29 f.

[10] Offences related to child pornography include the following conduct: a. producing child pornography for the purpose of its distribution through a computer system, b. offering or making available child pornography through a computer system, c. distributing or transmitting child pornography through a computer system, d. procuring child pornography through a computer system for oneself or for another person, e. possessing child pornography in a computer system or on a computer-data storage medium, see Art. 9 of the Europe Convention on Cybercrime.

[11] See ITU publication (n 1) p 21 f.

[12] See Jason Bloomberg, ‘Using Bitcoin Or Other Cryptocurrency To Commit Crimes? Law Enforcement Is Onto You’, https://www.forbes.com/sites/jasonbloomberg/2017/12/28/using-bitcoin-or-other-cryptocurrency-to-commit-crimes-law-enforcement-is-onto-you/

[13] See ITU publication (n 1) p 28.

[14] See ITU publication (n 1) p 29.

[15] Electronic evidence is defined as data that is created, manipulated, stored or communicated by any device, computer or computer system or transmitted over a communication system, that is relevant to the process of adjudication, see Stephen Mason, ‘International Electronic Evidence’, (British Institute of International and Comparative Law, 2008), Introduction, p xxxv.

[16] See Council of Europe, ‘European Committee on legal co-operation (CDCJ), The use of electronic evidence in civil and administrative law proceedings and its effect on the rules of evidence and modes of proof, A comparative study and analysis’, report prepared by Stephen Mason, CDCJ (2015) 14 final, Strasbourg, 27 July 2016.

[17] In particular films, cassettes, tapes and such like (as well as copies) may be admitted by the courts as real evidence. In the case of Eparhos Lemesou v Giorgalla [2003] 2 CLR 298, the Appeal Court of Cyprus considered the admissibility of evidence recorded with mechanical means. The judge in that case referred to the English case of R v Maqsud Ali, R v Ashiq Hussain, [1966] 1 QB 688, where the police recorded a conversation between two persons who were the suspects for a murder and had willingly attended the offices to Bradford City Council to be interviewed. Their conversation in Punjabi dialect was recorded without their knowledge, later it was translated into Urdu and then into English. The Court of Criminal Appeal decided that it was correct to admit a tape recording as evidence because there is no difference between a photograph and a tape recording. For that case see thoroughly Olga Georgiades, ‘Cypurs’ in Mason (n 13), p 147, 149.

[18] Codice penale, Regio Decreto, n 1398, 19 October 1930.

[19] See Fredesvinda Insa and Carmen Lázaro, ‘Admissibility of electronic evidence in court: A European project’ in Mason (n 13), p 4.

[20] German criminal courts do not recognize a general ‘fruit of the poisonous tree doctrine’ by which the exclusion of one item of illegally obtained evidence extends to all further items of evidence that have been discovered as a result of the first item. That means, that even if an item of evidence is gathered in violation of procedural law or in violation of constitutional rights, subsequent evidence, if obtained legally, may be introduced to the main trial, see Dr Alexander Duisberg and Dr Henriette Picot, ‘Germany’ in Mason (n 13), p 327, 349. In Greece, even unlawfully obtained evidence can be taken into account by a court. Criminal court have taken a more liberal view in this interpretation and have recently accepted videotapes and security cameras as evidence, Supreme Court 874/2004 published in [2004] Criminal Justice (PoinDik), 806, see also the decision of the same Court 954/2006 published in legal database Nomos, see Michael Rachavelias and Thanos Petsos, ‘Greece’, in Mason (n 14), p 351, 376.

[21] See Insa and Lázaro, (n 18) p 11.

[22] In Belgium, two specific computer crime investigation measures are available: data seizure and network searching. The investigating judge may decide to make a copy of a hard disk to put I on a hard disk (data seizure) or may order a search of the network if it is deemed necessary to reveal the truth (network searching), see Joachim Meese and Johan Vandendriessche, ‘Belgium’, in Mason (n 13), p 65, 101.

[23] Art. 427 Code of Criminal Procedure, see Judge David Benichou and Ariane Zimra, ‘France’ in Mason (n 13), p 303, 317.

[24] Metadata is data about data. I.e. in electronic documents metadata tends to be information which is hidden from the replication of the text as viewed on a screen. See Stephen Mason (ed), Electronic Evidence: Disclosure, Discovery & Admissibility, (LexisNexis Butterworths, London, 2007) para 2.09.

[25] The metadata in relation to a piece of paper may be: Expicti from perusing the paper itself, such as the title of the document, the date, the name of the writer, who received it and where the document is located. Implicit, which includes such characteristics as the types of type used, such as bold, underline or italic etc., see Mason, ibid.

[26] In Ireland, metadata was considered important for authenticating the provenance of electronically created documents/materials, (Koger Inc. & Koger (Dublin) Ltd v O’Donnell & Others [2010] IEHC 350), http://www.courts.ie/Judgments.nsf/0/1F8979ED6FCCF69C802577CB003B6360.

[27] Information concerning the location of the suspect’s phone might allow law-enforcement agencies to identify his location, See ITU publication (n 1) p 230.

[28] Regulation (EU) No 910/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 July 2014 on electronic identification and trust services for electronic transactions in the internal market and repealing Directive 1999/93/EC, (OJ L 257, 28.8.2014, p. 73)

[29] For example in Austria particularly in respect to electronic evidence, the judge tends to rely on an expert statement as to the authenticity of such evidence, if any doubts arise, see Wolfgang Freund, Erich Schweighofer and Lothar Farthofer, ‘Austria’ in Mason (n 13), p 43, 63.

[30] In China, the Hangzhou Internet Court confirmed on June 28, 2018 ruled, in a copyright infringement case, that blockchain-based evidence was legally acceptable. The collected data should have digital signatures, reliable timestamps and hash value verification or they can also be collected via a digital deposition platform. The usage of a third-party blockchain platform that is reliable without conflict of interests provided the legal ground for proving the intellectual infringement. Meaning that internet courts have to accept blockchain evidence as legal when used as a method for storage of authentication of digital evidence, see http://www.xinhuanet.com/2018-06/28/c_1123051280.htm.

[31] In USA, 2016 Vermont Statutes Title 12 - Court Procedure Chapter 81 - Conduct Of Trial Subchapter 1: § 1913 Blockchain enabling, provides: ‘1. A digital record electronically registered in a blockchain shall be self-authenticating pursuant to Vermont Rule of Evidence 902, if it is accompanied by a written declaration of a qualified person, made under oath, stating the qualification of the person to make the certification and: a) the date and time the record entered the blockchain, b) the date and time the record was received from the blockchain, c) that the record was maintained in the blockchain as a regular conducted activity and d) that the record was made by the regularly conducted activity as a regular practice’.

[32] A Blockchain-based platform will give regulators, auditors, and other stakeholders an effective and powerful set of tools to monitor complex transactions and immutably record the audit trail of suspicious transactions across the system, see Bloomberg (n 11).

[33] Digital evidence is becoming important even in traditional investigation, as in a murder trial in the US, in which records of search-engine requests stored on the suspect’s computer were used to prove that, prior to the murder, the suspect was using search engines to find information on undetectable poisons, see ITU publication (n 1) p 227.

[34] I.e. in most cases of electronic crimes in Greece, mostly in respect of child pornography the process followed by the police is first to trace the whereabouts of the accused by following the evidence left on the Internet, then to seize all electronic devices or storage media at the home or workplace of the accused before examining the hardware in special forensic laboratories by specialized personnel, see Rachavelias and Petsos, (n 19), p 351, 372.

[35] The Supreme Court of Italy (Cass sez V, 19.3.2002, n. 2816, Manganello, in CP 2004, 1339) allowed for example the seizure of an entire sealed server of a lawyer under investigation in order to verify the content. In another case the same court (Cass sez III, 3.2.2004, n. 1788) held that it was not useful to seize an entire system with regard to the parts that is considered neutral (such as the printer and monitor), see Cristina Pavarani and Luigi Martin, in Mason (n 13), p 433, 466.

[36] In Spain the disclosure of electronic files at trial may be undertaken at the request of the parties (once admitted by the judge) as well as by virtue of the powers granted within certain limits to the court (Art. 729.2 LECrim), see Julio Pérez Gil, ‘Spain’, in Mason (n 13), p 835, 862.

[37] See ITU publication (n 1), p 228 f.

[38] Suspicious search-engine requests might lead to the location of a missing victim. For a case where search-engine requests were used as evidence in a murder case see Jones, Murder Suspect’s Google Search Spotlighted in Trial, Informationweek.com, 11.11.2005, available at: www.informationweek.com/news/internet/search/showArticle.jhtml?articlelD=173602206.

[39] ITU publication (n 1) p 237.

[40] Ibid, p 229.

[41] Internet Service providers (ISPs) play an important role in many cybercrime investigations, since many users utilize their services to access the Internet or store websites. Furthermore the ISPs have the technical capability to detect and prevent crimes and to support law-enforcement agencies in their investigations, see ITU publication (n 1) p 241.

[42] Directive 2014/41/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 3 April 2014 regarding the European Investigation Order in criminal matters, OJ L 130, 1.5.2014, p.1.

[43] Council Act of 29 May 2000 establishing in accordance with Article 34 of the Treaty on European Union the Convention on Mutual Assistance in Criminal Matters between the Member States of the European Union.

[44] Council Decision 2002/187/JHA of 28 February 2002 setting up Eurojust with a view to reinforcing the fight against serious crime. In 2013, the Commission adopted a proposal for a Regulation to reform Eurojust (Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the European Union Agency for Criminal Justice Cooperation (Eurojust), COM/2013/0535 final).

[45] Regulation (EU) 2016/794 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 May 2016 on the European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Cooperation (Europol) and replacing and repealing Council Decisions 2009/371/JHA, 2009/934/JHA, 2009/935/JHA, 2009/936/JHA and 2009/968/JHA.

[46] Council Framework Decision 2002/465/JHA of 13 June 2002 on joint investigation teams.

[47] Council Decision 2009/820/CFSP of 23 October 2009 on the conclusion on behalf of the European Union of the Agreement on extradition between the European Union and the United States of America and the Agreement on mutual legal assistance between the European Union and the United States of America.

[48] Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on European Production and Preservation Orders for electronic evidence in criminal matters, COM(2018) 225 final.

[49] Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council laying down harmonised rules on the appointment of legal representatives for the purpose of gathering evidence in criminal proceedings, COM (2018) 226 final.

[50] Council Framework Decision 2001/413/JHA of 28 May 2001 combating fraud and counterfeiting of non-cash means of payment (OJ L 149, 2.6.2001, p. 1).

[51] Directive 2011/93/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 December 2011 on combating the sexual abuse and sexual exploitation of children and child pornography, and replacing Council Framework Decision 2004/68/JHA (OJ L 335, 17.12.2011, p. 1).

[52] Directive 2013/40/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 August 2013 on attacks against information systems and replacing Council Framework Decision 2005/222/JHA (OJ L 218, 14.8.2013, p. 8).

[53] Directive (EU) 2017/541 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 March 2017 on combating terrorism and replacing Council Framework Decision 2002/475/JHA and amending Council Decision 2005/671/JHA (OJ L 88, 31.3.2017, p. 6).