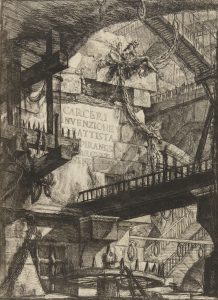

Giovani Battista Piranesi (1720-1778) was born near Venice and died in Rome where he spent a considerable part of his life. He was an architect and a printmaker. Practically speaking his professional activity as an architect was limited. The unique project he completed was the church of Santa Maria del Priorato in Rome (1764-1766). Yet as an engraver, in the tradition of Rembrandt, Dürer, Goya, Roualt and Picasso, he was among those to whom this art owes its title of nobility. He became famous for his engravings of subjects of archaeological interest entitled Views of Rome. Just as the sequence known as the Carceri d’invenzione [or “Imaginary Prisons”] was highly acclaimed. In the definitive version, the Carceri formed a series of 16 engravings that were printed in 1761.

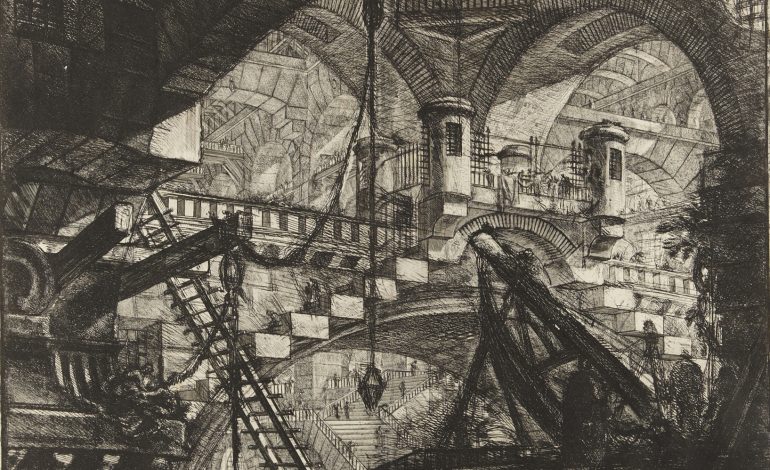

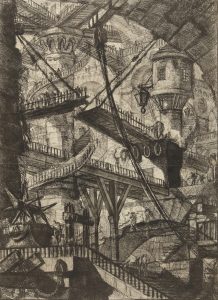

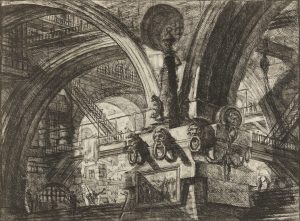

They are fictitious spaces that recall the inner parts of medieval towers where everything has assumed gargantuan proportions. Giant columns, tackling and pulleys with chains suspended threateningly, engines of torture, toothed wheels like those familiar from the iconography associated with Saint Catherine. Series of vaults in succession and meandering stairs with countless vanishing points that extend the space infinitely in every direction. With the pronounced shadows and sharp lighting these places give you the impression that you’re in a labyrinth, trapped in a mechanism that overruns you. According to Marguerite Yourcenar it is “an artificial world that is nevertheless real in a sinister way, claustrophobic, megalomaniacal that brings to mind modern man who shuts himself away more each day.”[i]

These works by Piranesi with their intensely dramatic character recall opera stage sets. Moreover, it is known that the first “Prison” that Piranesi engraved “Carcere oscura,” which does not belong to this series, is occasionally referred to as “Prison of Dardanus” because it was later used as a maquette for the stage set of Dardanus by Jean Philippe Rameau (1739). Of course, the comparison with cinema is automatic. Anyone who is a fan of black and white film will readily ascertain the affinities, as much with light as with the intricate arrangement of the space.

Viewing the “Prisons” one quickly discerns the striking fact that all those giant constructions serve no purpose, just as the chains never restrained an inmate (with the exception of Etchings II and X). Likewise, the wheels have remained motionless and the staircases lead nowhere.

- Etching X: Prisoners on a Projecting Platform

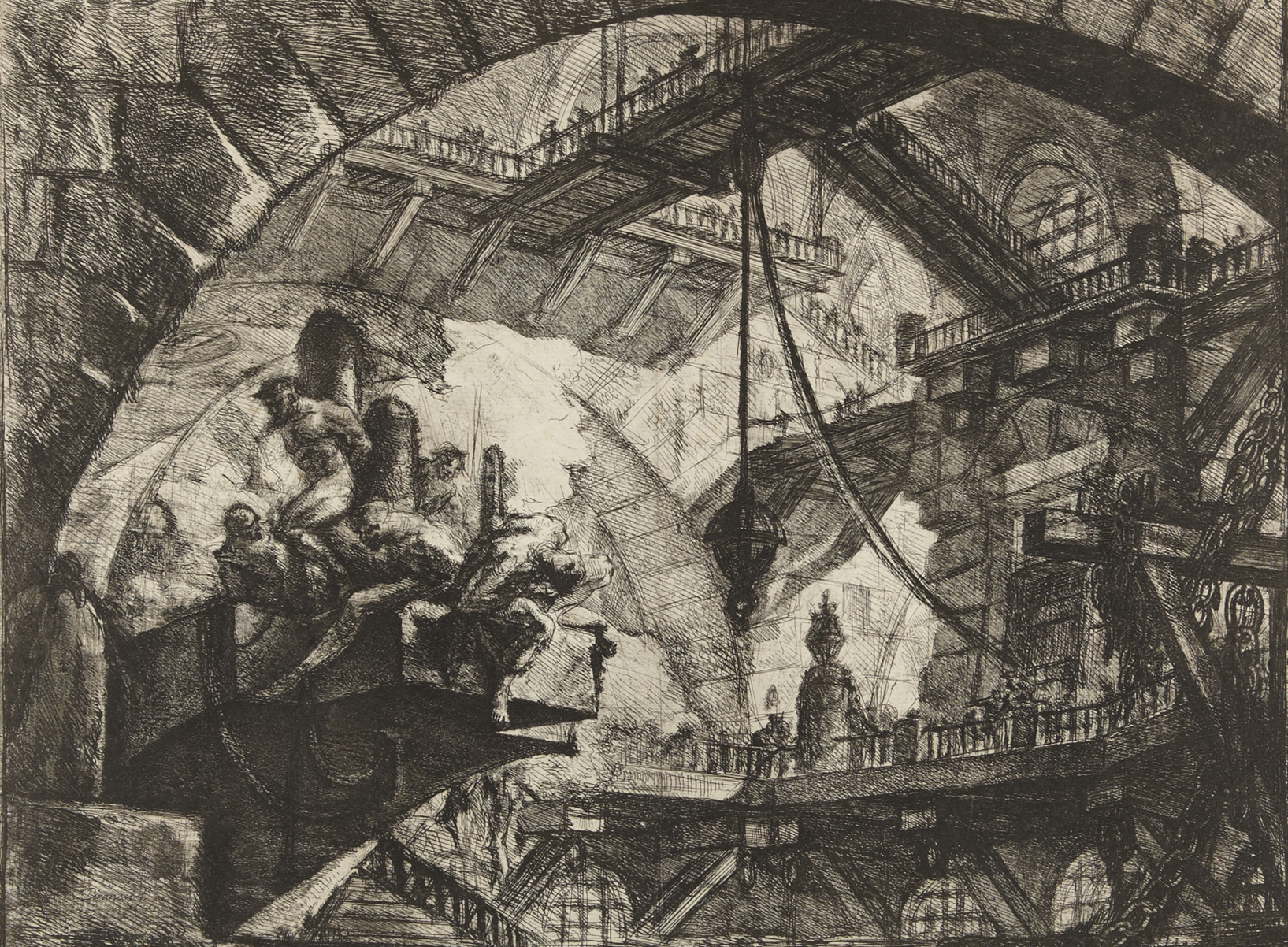

- Etching II: The Man on the Rack (detail)

The similarities between the oeuvre of Piranesi and Kafka’s are manifest and run through the latter’s work in its entirety. More specifically, there is a description of the labyrinth in the short story “The Burrow.” Also in “Advocates,” a very succinct story, we come across the following paragraph: “So if you find nothing in the corridors open the doors, if you find nothing behind these doors there are more floors, and if you find nothing up there, don’t worry, just leap up another flight of stairs. As long as you don’t stop climbing, the stairs won’t end, under your climbing feet they will go on growing upwards.” The architect of this space seems familiar…

Just as here, in my opinion, we can find a possible explanation for all that idleness and desuetude into which sinks everything in Piranesi’s prisons in the following terse parable by Kafka from the same collection of short stories. Here Kafka tells us: “There are four legends concerning Prometheus: According to the first he was clamped to a rock in the Caucasus for betraying the secrets of the gods to men, and the gods sent eagles to feed on his liver, which was perpetually renewed. According to the second Prometheus, goaded by the pain of the tearing beaks, pressed himself deeper and deeper into the rock until he became one with it. According to the third his treachery was forgotten in the course of thousands of years, forgotten by the gods, the eagles, forgotten by himself. According to the fourth everyone grew weary of the meaningless affair. The gods grew weary, the eagles grew weary, the wound closed wearily.

There remained the inexplicable mass of rock. The legend tried to explain the inexplicable (…).” [ii] Thus, here we have a probable answer. As if the people who built these prisons, who made all these instruments of torture to extract some truth even with the use of violence, who concocted all these colossal constructions - they ultimately relinquished every kind of pursuit. As if all efforts to find some meaning are doomed to reach the same impasse and as such the mystery remains impenetrable.

Perhaps this is how to explain the huge heads in relief (Etching II) befitting a metaphysical painting the likes of a de Chirico and that appear to allude to the second version of the myth. Besides this stagnation so dense with symbolism, there is a second paradox. These places, although they preserve all the features of the Baroque, they remain almost uninhabited. The rare human figures, so diminutive in proportion to the vastness of the space, when they do appear they are rendered indifferently in a few hasty lines that merely hint at a presence. The dramatic action and theatrical gestures that we were accustomed to seeing in painting up until this point, have withdrawn from center stage in these etchings by Piranesi. I believe that in this is presaged a “modern” gaze/perception of painting. Painting that does not narrate stories but instead evokes states of being, painting which does not name things but intimates them.

- Etching II: The Man on the Rack

- Etching II: The Man on the Rack (detail)

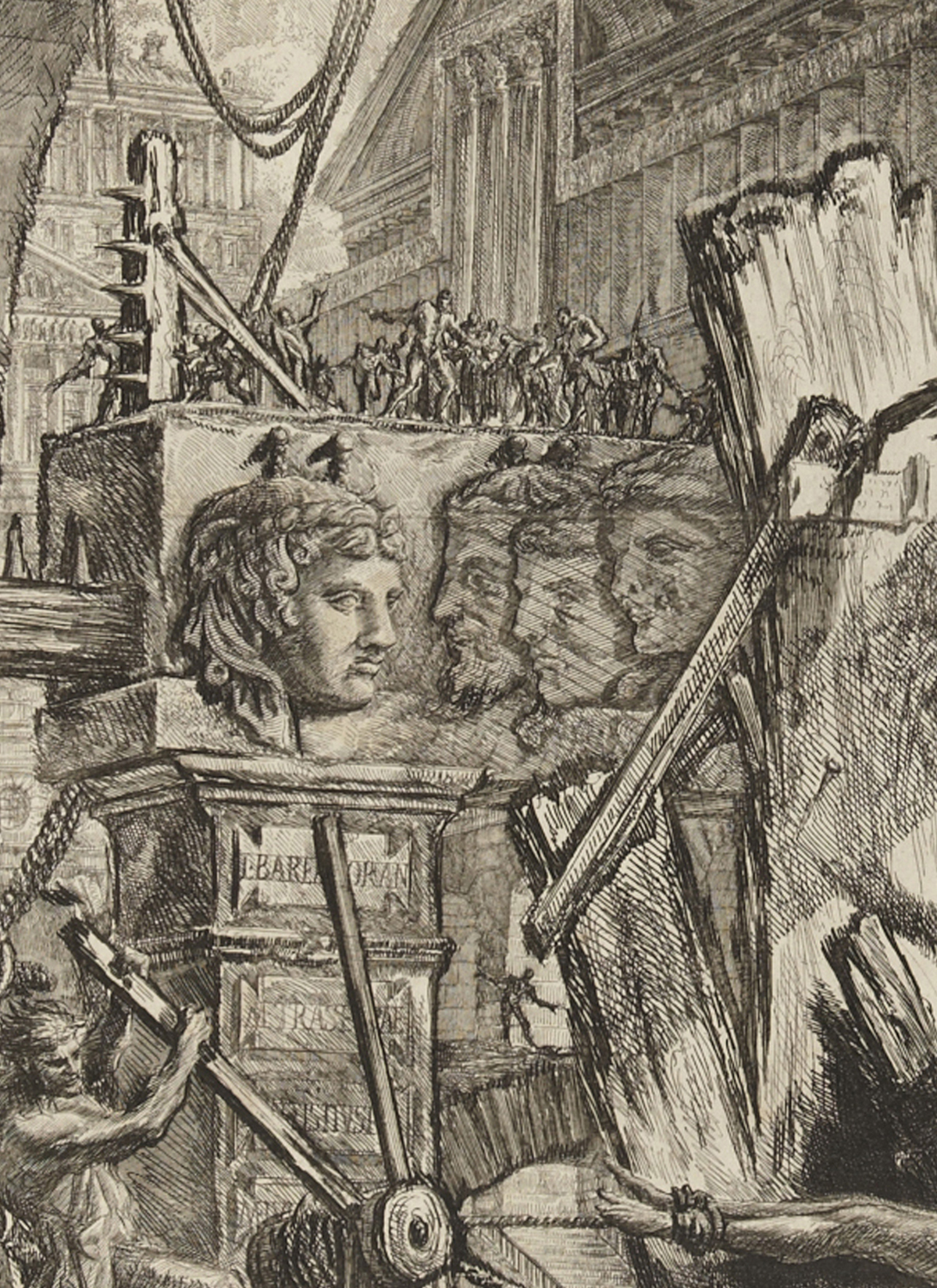

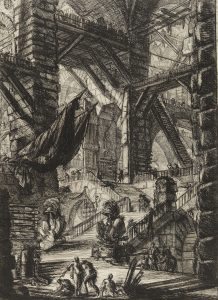

In Etching III on the lower right where we see darkened windows with a slight slope towards the bottom, we have the impression that we are plunging into a subterranean world, into chaos. Maybe this is the most forbidding point in the work. Even more than the massive arches, the round tower with walled-up windows and the omnipresent pulleys. Those windows in the bottom right-hand section promise an even murkier world, more fearsome than all the torture devices, precisely by means of suggestion.

The importance of the Imaginary Prisons becomes evident from the reception the future had reserved for them – given the extent to which these figments fertilized the imaginations of such a vast and varied spectrum of creators. Each one of their “reincarnations,” each time their influence can be detected in the work of subsequent artists, a different facet of their physiognomy comes to light.

- Etching III: The Round Tower

- Etching III: The Round Tower (detail)

It is worth mentioning the example of Théophile Gautier because he was aided by Piranesi in his efforts to give form to his hallucinatory experiences. As he himself relates in his essay Le Club des Hachichins [The Club of Hashish-Eaters]: “By this time, I had reached the head of the stairs, which I undertook to descend; they were half-lit, and through my dream they took on Cyclopean, gigantic proportions. Their two ends, bathed in shadow, seemed to plunge into heaven and hell, both of them abysses; raising my head, I indistinctly discerned, in a prodigious perspective, countless, superposed landings, ramps leading up as to the top of the tower of Lylacq; looking down, I felt the presence of abysses of steps, whorls of spirals, circumvolutions. This staircase must pierce the earth through and through, said I to myself as I continued my mechanical walking. I shall reach the bottom the day after Judgement Day.”[iii]

And a little further on: “To convey the impression of tenebrous architecture I would need the point of the needle with which Piranesi etched the black varnish of his marvelous copperplates.” Piranesi gives Gautier the means to fully express his experimentation with hashish while at the same time Gautier also offers us an approach to the work of Piranesi. In one of his poems Victor Hugo speaks of “Le cerveau noir de Piranèse” [The Dark Brain of Piranesi]. Marguerite Yourcenar in turn borrows this verse as a title for her essay on Piranesi. Likewise, there is a short story by Jorge Luis Borges “The Library of Babel” where he describes a universe that has much in common with the cosmos of the Imaginary Prisons. It begins as follows: “The universe (which others call the library) is composed of an indefinite number of hexagonal galleries. In the corner of each gallery is a ventilation shaft, bounded by a low railing. From any hexagon one can see the floors above and below – one after another, endlessly. The arrangement of the galleries is always the same […] One of the hexagon’s free sides opens onto a narrow sort of vestibule, which in turn opens onto another gallery, identical to the first – identical in fact to all. […] Through this space too passes a spiral staircase, which winds upward and downward into the remotest distance.”[iv]

Whether it’s the Prometheus myth, Kafka’s labyrinth, Gautier’s hashish-induced hallucinations, Hugo’s “cerveau noir de Piranèse,” or Metaphysical Prisons as Aldous Huxley called the etchings “whose seat is within the mind, whose walls are made of nightmare and incomprehension, whose chains are anxiety and their racks a sense of personal and even generic guilt,” [v] or scenes from the cinema starting with Metropolis by Fritz Lang, Strike by Eisenstein, The Third Man by Carol Reed [especially the chase scene in the sewers], Blade Runner and The Name of the Rose – they are all evidence and arguments for the inexhaustible dynamism of Piranesi’s Imaginary Prisons but also proof of the fundamental truth that a work of art lives on and is recreated in the gaze of viewers, readers and art lovers and unquestionably contains far more than its creator ever suspected.

[i] Marguerite Yourcenar, The Dark Brain of Piranesi and Other Essays, transl. Richard Howard with the author, New York, Farrar, Straus, 1984.

[ii] Franz Kafka, The Complete Stories, with a foreword by John Updike, Schoken Books, 1971, pp. 432, 451.

[iii]Charles Baudelaire, Les paradis artificiels précédé de Théophile Gautier, Le Club des Hachichins, Gallimard, Folio, 1961, “Tread-Mill” pp.62-64 [Artificial Paradises, The Club of Hashish-Eaters].

[iv] Jorge Luis Borges, “The Library of Babel” in Collected Fictions, Trans. Andrew Hurley, New York, Penguin, 1998, p.112.

[v] Aldous Huxley, Prisons. With the “Carceri” etchings by G.B. Piranesi, Trianon Press, London, 1945

- Etching I: Title Plate

- Etching IV: The Grand Piazza

- Etching V: The Lion Bas-Reliefs

- Etching VIII: The Staircase with Trophies

- Etching XIΙI: The Well

- Etching XIV: The Gothic Arch

- Etching XV: The Pier with a Lamp

- Etching XVI: The Pier with Chains

![Hang ’Em High (1968) [Κρεμάστε τους ψηλά] <br/>Αυστηρότητα και επιείκεια ως στοιχεία <br/>της θετικής γενικής πρόληψης](https://theartofcrime.gr/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/morozinis_cover_nov21-237x143.jpg)