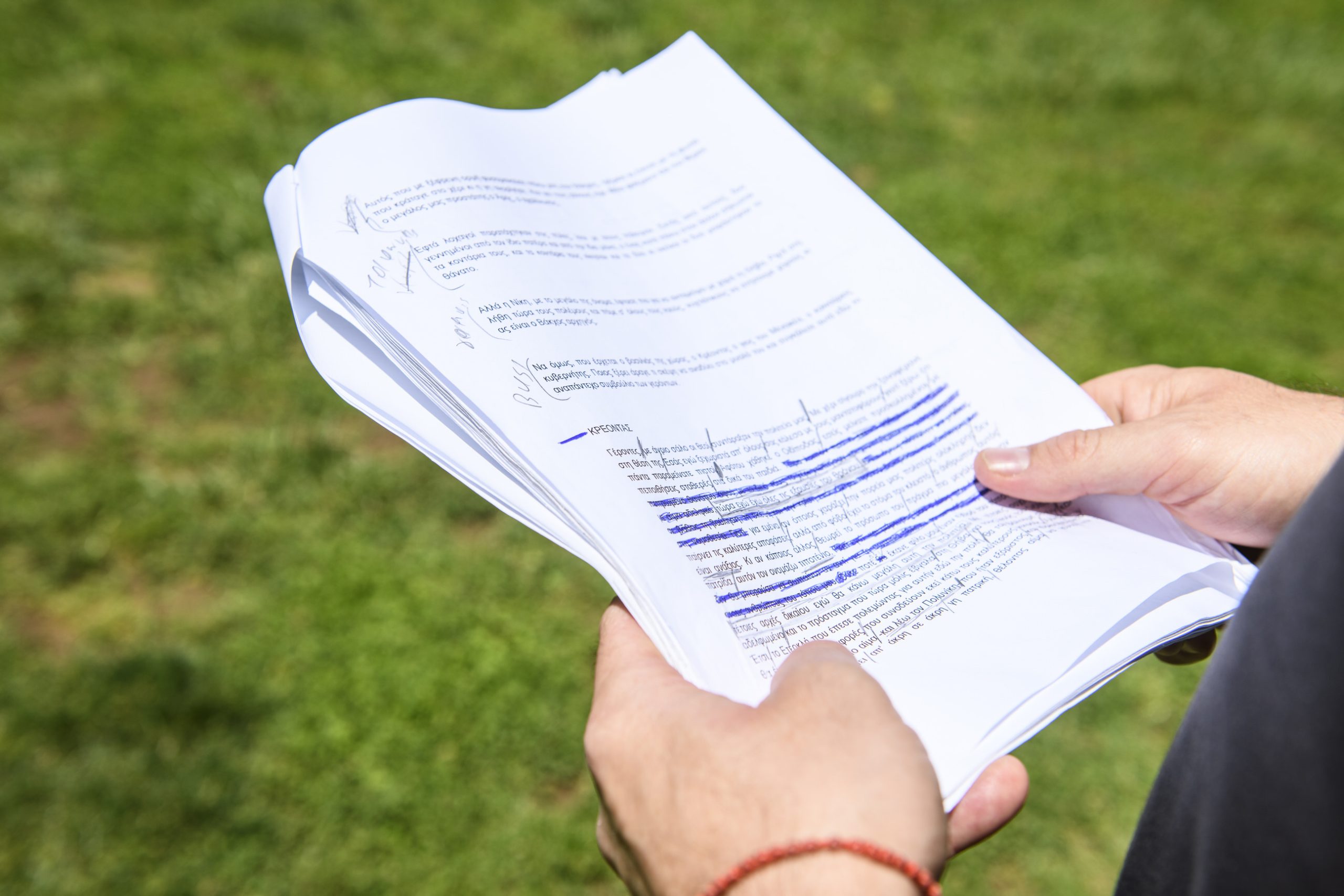

Image: Elina Giounanli

The theatre workshop

Since 2016, the Korydallos Penitentiary Detention Facility I has been operating a theatre workshop for prisoners with the approval of the General Secretariat for Anticrime Policy. The facility, very close to the center of Athens, is the largest detention center in Greece. It accommodates between 1,600 and 2,000 adult male prisoners and is mainly a detention facility for defendants. However, there is also a significant proportion of convicts who remain there either for educational reasons, i.e. to attend university schools, or because it has been deemed more appropriate on legal and institutional grounds. The establishment consists of six wings. The placement of prisoners in the respective wing takes into account the place of origin of each prisoner, his mental health and his safety.

The initial design and operation of the workshop aimed simply at staging a theatrical play. The last two years, the activities of the workshop have expanded to other areas of theatre education, such as guided improvisation, basic acting principles, dramatic editing, etc. The participants are prisoners who have shown interest and have been appointed by the competent prosecutor of the institution. Therefore, permits are granted to prisoners who apply in writing for participation in the drama workshop program, and are deemed by the sociologists and prosecutors of the establishment as fit to join the group. The criteria for acceptance of applications do not relate to the criminal profile of the applicant in question, but to his attitude and behavior during his stay in the establishment.

Due to the great popularity and recognition that the workshop has gained over the years within the prison population, in 2023 it was decided to expand its activities. Today, the program takes place two to three times a week for three hours and is annual (October-June). Its aim is to bring together a larger group of participants who are introduced to various theatrical practices and processes, from dramaturgy to improvisation. In the last trimester of the workshop, participants focus on intensive preparation work for the final staging.

The expansion and continuation of the program keeps diversifying the profile of the participants. During its first years, the workshop happened to involve mostly educated prisoners, that is, prisoners who had completed secondary education and in some cases were continuing their studies at university schools. In addition, the members of the team at the time were limited in number. Nowadays, most of the workshop members come into contact with theatre for the first time through the workshop. The vast majority of the group members in 2023-2024, more than 70%, had not completed secondary education. It is noteworthy that various ways have been found to ensure that even a lack of primary education does not act as a deterrent or barrier to their participation in the group. The group is quite heterogeneous both in terms of the criminal profiles of its members and because of age and racial differences. On an annual basis, the group involves an average of 35 to 40 prisoners, of which 25 to 30 end up participating in the final staging.

By common admission of all the participants, the existence of the workshop is an escape from their grim daily life at the detention center, as they engage in something that is new to them. However, the key question is whether and how their participation in the theatre workshop can also be considered a powerful correctional process that experientially enhances their social skills, activating, awakening and cultivating their way of thinking.

As the director and animator of the workshop since 2023, I can attest that over the course of these months (October-June) I observed people shifting tremendously. My conclusion stemmed from the changes I noted in their engagement, their willingness and their behavior within the group. Their initial suspicion and a slightly dismissive attitude towards the whole project developed into systematic intellectual and emotional engagement and commitment to the group. This, of course, does not stand as a full answer to the above question, but it does point to the potential of the workshop to nurture patterns of behavior that may be gradually adopted by the participants. It is worth looking at how these patterns can influence and determine their development, assuming this is not already happening to some extent.

It should be noted that, particularly in theatre, artistic creation is an experiential process in which one must be present body and soul, and combine a wide range of information while also translating it into personal creative actions and decisions. As I gradually got to know the participants in the group, the most shocking thing for me was the realization that it was pointless to search in their personal narratives for some positive experiences in their lives, as one might misleadingly call them. In most cases, the dominant experience was delinquency and a marginalized life into which they had been led either as a last resort or because their upbringing and their perceptions had nothing else to offer. This was followed by the unrelenting experience of punishment and incarceration. Personally, I could not see how people with that kind of experience would serve their sentence and leave the detention facility without returning to their previous life. If they avoid recidivism – which is the whole point – my guess is that this will happen because of fear, not because of any success in the correctional process.

Driven by the above personal observation, I have set as the main goal of the theatre workshop the gradual creation of a positive experience for the participants, an experience they will work hard for but that will lead them to fulfilment, not frustration. Thus, together with the team members, we established the rules of cooperation and conduct of the workshop. Each rule corresponded to a proposal by one of the participants. In addition, we collectively set the artistic goals of the year. I personally emphasized in particular that within the group I would like them to think of themselves first and foremost as actors and co-creators, not as prisoners.

This commitment between us was the springboard for all the actions that were implemented and led us to the successful staging of Sophocles’ Antigone in June 2024. The play was presented for three consecutive days to different audiences. The first staging was attended by a different population of prisoners of the establishment, the second by guests of the management of the establishment and of the artists who contributed to the staging, and the last one by relatives and friends of the prisoners who played the leading roles.

The tragedy and the prisoners’ preference for Creon

The choice of Antigone was of key importance with regard to the development of the whole process, as it created a broad field of thought and discussion that was also directly related to current issues in the life of the group members. Sophocles’ Antigone is one of the most emblematic works of Ancient Greek literature, dealing with issues such as the conflict between moral values and state law, faith in the family and individual freedom.

The plot is set in Thebes, after the tragic battle between the two brothers, Eteocles and Polynices, who kill each other in a struggle for power, having previously caused a civil war. King Creon, the new leader of Thebes, decides to honor Eteocles as a hero, but to leave Polyneices unburied, as he is considered a traitor. This decision violates religious traditions, which require that the dead be returned to the earth, but at the same time acts as a deterrent to anyone who might attempt to cause civil strife in the future. Antigone, the sister of the two dead, decides to defy Creon’s decree and bury Polyneices, which leads her into conflict with Creon. While she insists that her act is just and divinely appropriate, Creon arrests her and sentences her to death for breaking the law. Antigone is locked up alive in a cave by Creon. There, she decides to commit suicide instead of waiting to die of starvation. Then Creon’s son and Antigone’s lover, Aemon, commits suicide as well, and his mother Eurydice, Creon’s wife, follows suit, sending the king into utter grief.

Antigone is a work of profound moral and philosophical value that reflects on what is just and which is the proper place of the individual in relation to laws and authority. In the play, the written law clashes with the unwritten law, and their representatives are both defeated, while the Chorus, i.e. civil society, tacitly accepts the arbitrariness of political leadership. Although civil society comments, mourns and sometimes despairs, they still accept and choose to remain silent, taking a stand only at the very last instance, when it is too late, and the conflict has already proved fatal and destructive.

At hearing the story of the play and reading the text, the members of the group were initially surprised. They recognized that Antigone’s punishment was disproportionate to her act. Nevertheless, there was a strong tendency to embellish Creon’s attitude and decisions. Personally, I expected that their stance would be in favor of Antigone, as she is the character who selflessly clashes with law and authority. I thought that such a person would be a heroic symbol for the group of prisoners, and I was prepared to analyze as a counterpart Creon’s reasoning in order to have a fruitful dialogue.

Yet their beliefs were almost entirely contrary to what I expected. The first thing about Creon upon which the group unanimously agreed was that “he could not help it, he had given his word, and to take it back would be a sign of weakness”. When I asked them if they thought Antigone was to blame for anything, they said no, just that what happened to her was a necessary evil, as Creon should not and could not back down. A bit as a provocation, I started calling Creon a “tyrant”. Most members of the group paid no attention to my phrasing, with the exception of one prisoner who pointed out to me again that Creon had no choice but to be merciless in order to maintain his power.

Spurred by this attitude, I asked them if in their own lives they themselves had been more Creon or Antigone. Unanimously. they all sided with Creon. As they explained to me, Creon is a leader and has a natural claim to power and authority, which is exactly what they themselves claimed. If he were to back down, he would have been left exposed and his position would have been jeopardized. Most of them argued that Creon was certainly scared when he learned that public opinion was not on his side, but to allow his fear to determine his decisions would be a sign of weakness and defeat. Some even pointed out that in their own lives there had been occasions when they should have backed down to avoid arrest, but for reasons of honor and because they had given their word there was no way they would not keep it.

Following all of the above, one of the most eloquent members of the group stated that “Creon is making a desperate attempt to maintain his power and honor, just as we did before our arrest”. Sticking to this discussion on the basis of personal identification, I asked them if in their lives, even when they behaved like Creon, they could intimately pity or sympathize with Antigone. “When you’re trying to maintain your power, you can’t do that, it's like saying I sell drugs but at the same time I feel sorry for those who take them. You just can’t. An outlaw has no feelings, just like Creon had no feelings. Antigone was a heroine, she fought for love and forgiveness, but we are not heroes”. Impelled by this, I asked them whether, if they could go back in time, they would change their lives by choosing Antigone’s attitude over Creon’s. Some replied with condescension, however the majority agreed that they would like to live in a world where they could be Antigone without this stance leading them to death.

The tragic conflict and the question of justice

“In a court of law who would you support?”, was my next question, and they all agreed that they would side with Antigone, because she is the weaker of the two parts. However, they felt that the one who would eventually win the case would be Creon, as he is the strong one. Bearing in mind that they identified themselves with Creon, I explained to them that this belief of theirs seemed to me paradoxical. They still insisted though that in a court of law they would not defend Creon, with whom nevertheless they identified, as, in their mind, they had much in common.

The members of the group defended themselves upon hearing my assertion about the self-contradictory nature of their position. They explained to me that they themselves behaved like Creon on an emotional level because they felt they had power in their hands. However, in reality they never had institutional power like Creon. In light of this, they argued that people who have power in their hands and try to maintain it develop similar characteristics, regardless of whether the power they have is state- or drug-related.

Elaborating on the above conclusion, the oldest of the participants stated that “we as Creon have also wronged people and that’s why we are here, yet we didn’t do it because we wanted to hurt anyone but because we wanted to benefit ourselves, and that’s where we got blinded and fucked up. It’s not really Antigone’s fault or Creon’s fault. If anyone is to blame, it’ the Chorus, who sees but does not speak. I agreed with this statement, explaining that indeed the biggest problem in the development of the play may be the Chorus, civil society, which uncritically accepts the arbitrariness of political leadership and does not act or take a stand against the tide until it is too late. I asked them to think of a contemporary example that illustrates the attitude of the Chorus, or at least to formulate a socio-political conclusion based on their observation of the Chorus’ stance. The answers I received were rather vague, mostly reduced to phrases such as “humans are animals” and “indifference is the greatest evil”.

From the whole conversation it was obvious to me that although they identified with Creon’s choices, it was not clear to them which of the two characters was right in this conflict. The process of analyzing and interpreting a text within the group could not follow the normal process in theatre, as one might call it. Specifically, it is customary, in the context of the dramatic treatment of a text, to analyze something specific as something general, that is, to read a story with a view to its socio-political implications. In this case, the tendency was exactly the opposite. The majority of the group members were trying to use the play as a basis in order to understand and interpret their own personal choices.

As I kept trying to elicit some belief that might lead them to express their opinion about which of the two characters is morally and legally wrong, I asked them how they would describe the plot of the play to a thirteen-year-old. Their answers were divided. One of the participants, who is also a father, claimed that he would encourage his son to nurture Antigone’s magnanimity but behave like Creon, because that would enable the boy to man up against the grim reality that awaits him. Another prisoner would urge a child to maintain his morals, just as Antigone did, even if the consequences were painful. Driven by the aforementioned position, one person disagreed, saying that he would encourage his child to stand up for himself but not break the laws lest he face painful consequences.

The most eloquent view was stated by a young prisoner: “I would like my child to fully identify with Antigone, because she did not hesitate to stand up to a king who was wronging her. That makes her a heroine, and in our time we lack heroes. Everyone backs down because they are afraid. They fear the laws, the system, the powerful ones, and so we continue to live in a world that does not actually resist injustice. We must stand up for what we love and believe in, even if that comes at a cost. Heroes make history. There would be no play if it weren’t for Antigone”. This view clearly had a deep ideological, and in my view romantic, underpinning. I asked this participant whether in his view violence was allowed as a means to defend ideological beliefs. His answer was no, because, as he put it, with violence, justice is surely lost.

In general, although throughout the discussion all the members of the group showed a keen interest in the issue, I kept getting the impression that they expressed their views with less certainty than usual. I speculate that this was due to the ambiguity of the play: one has a deep feeling that there actually is a sound line of reasoning in both Antigone and Creon. Antigone acts on the basis of brotherly love, forgiveness and the justice of the gods, while Creon decides on the basis of order in the city, social organization, discipline and cohesion.

The members of the group pointed out that there is a substantial difference in the application of laws then (441 BC) and today. Back then, even the cruelest death penalty was considered perfectly logical, which fortunately is not the case today. On the basis of this finding, the members of the group agreed that if the sentence imposed on Antigone by Creon had not been the capital one, his action would have been entirely appropriate, as he was already acting with a view to maintaining social order, security and cohesion. In light of this latter assertion, I attempted to highlight Creon’s remorse at the end of the play, when he actually takes back his decision. For the members of the group, this was a minor event; they attributed it to Creon’s fear of losing his son and did not consider it to be directly relevant to the core of his conflict with Antigone. However, they strongly applauded the fact that even at the last minute he takes his son into consideration.

An interpretation of the prisoners’ attitude

Reflecting on our discussion and especially on the unexpected, in my mind, interpretations and remarks of the group members, I attempted to interpret their positions. First of all, I return to an issue briefly mentioned above. Although an educational and certainly a dramaturgical analysis of a play would require participants to generalize the issues of the particular play into broader social and political domains, this methodological process seemed to be completely foreign to this group. This of course can be justified by the educational level of the group. However, I too guided the discussion with the intention that each person would seek their own personal area of identification with the project, which is what happened. The difficulty lies in the extent to which the group itself could have been led to further and broader sociological conclusions impelled by their own responses.

Subsequently, I speculate that the embellishment and acceptance of Creon’s attitude may also arise from a deeper need to understand and accept the circumstances which the group members find themselves in. Being in a state of confinement, they certainly feel to some extent that they are suffering the consequences of their actions. Therefore, their understanding of Creon’s cruelty towards Antigone, who in Creon’s opinion is in the wrong because she breaks the law, might reflect the prisoners’ need to understand the present conditions of their lives by justifying the decisions of the people who imposed them. It is possible that my interpretation involves a high degree of arbitrariness. However, it is based on their complete justification of Creon’s attitude, and in particular on their expressed view that if the sentence Creon imposed on Antigone had not been the capital punishment, it would have been perfectly justified.

Of course, the most interesting part probably comes from their identification of their own behavior with Creon’s. They recognize in a cruel, ungrateful and authoritarian leader characteristics that they themselves had in their own lives, with the element of honor being presented as the most important one. Not admitting fault and avoiding repentance so as not to appear weak seem to be two things that have not only concerned them but have also led them to key decisions in their lives. Creon’s selfishness, his excessive persistence, cruelty, disregard for others, authoritarianism and absoluteness are the characteristics that led him to a decision that hurt him, and these are precisely the features that the prisoners identified with and recognized as their own.

Furthermore, I take it that another difficulty in interpreting this particular play arises from the fact that the two central characters are defeated. The one fights until the end to avoid defeat, while the other fights knowing from the start that she will be defeated. Creon’s determination not to be defeated, in defiance of everyone’s suggestions, is what makes him most familiar and accessible to the members of the group. Conversely, the fact that Antigone knows that she will suffer the consequences of her actions and does not try to avoid them is what removes her from the prisoners’ field of identification. For some members of the group, this characteristic makes her a heroine, while for others it seemed so absurd and inexplicable that they were simply discouraged from getting involved with her character at all.

In light of the above characteristic of Creon, I asked the group members if they themselves, in their effort to prevail and avoid defeat, had faced grey areas, i.e. actions they would not engage in. The majority agreed that they would never harm the family of an “opponent” and that they would protect their own families at all costs. Thus, it is extremely interesting to observe how in of a group of prisoners who often tend to even embellish illegal acts other codes of conduct are also developed. Another typical example of an alternative code of conduct is the dismissive attitude of many members of the group towards heroin trafficking, which was even used as an example in their answers to the above question.

In summary, Creon seems to be characterized by two main traits that provoke the group’s interest as well as multiple identifications. As a king, he represents the face of law and power, he is the one who makes the decisions. On the other hand, his power is threatened, and he fights to maintain it. These two distinct characteristics of Creon are what trigger the group’s reactions. The first one is directly related to the criminal framework of their lives and to the people they have associated with because of it, while the second one stirs their emotions as they recognize elements of their own behavior and life in Creon’s struggle to maintain his supremacy.

As a conclusion, I return to my initial claim about the redemptive and, to some extent, rehabilitative process of theatre, and particularly of this specific play in a detention facility. The theatre workshop creates a framework for systematic discussion and analysis of the choices and decisions made by the characters in a play. In fact, understanding and performing a role requires a profound comprehension of the character’s intentions and thoughts, which encourages the group members to move away from their own subjective perception of certain issues and to adopt an entirely different way of thinking. The repetitiveness of this process, along with the fact that it takes place within a theatre workshop – a stable small community created within the detention facility – makes the whole endeavor worth observing for the potential benefits it may has to offer to the inmates. Personally, I will never forget the words of Nikos, the inmate who played Haemon, Creon’s son, and whose release was scheduled for the day of our staging. He called me five months after the premiere of Antigone to tell me that “what happens in the workshop is great, and for some people it is so helpful that they will never go back there. Don’t stop it. I was thinking about it this morning and I decided to call to let you know”.

![Hang ’Em High (1968) [Κρεμάστε τους ψηλά] <br/>Αυστηρότητα και επιείκεια ως στοιχεία <br/>της θετικής γενικής πρόληψης](https://theartofcrime.gr/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/morozinis_cover_nov21-237x143.jpg)