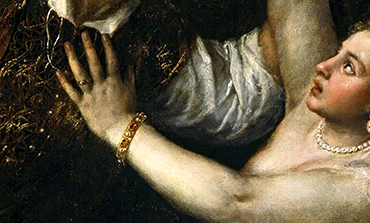

Τhe painting Tarquin and Lucretia by Titian (Tiziano Vecellio) [Figure 1] is a work dating from 1571, executed when the painter was in the eighth decade of his life[i] and painted for Philip II of Spain. After many peregrinations in various collections, finally in 1918 the painting found a permanent home at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge.

The work portrays the rape of Lucretia renowned for her virtue as spouse of the Roman General Collatinus and who was violated by the Etruscan Tarquin. According to Titus Livius [Livy][ii] while Collatinus was at war, Tarquin penetrated into Lucretia’s rooms and forced her by knife to succumb to his desires. Lucretia resisted with all her might and only when Tarquin threatened to kill her and one of his slaves then leave their naked bodies as proof of adultery, did she yield. When her husband returned from war, Lucretia confessed that she had been defiled and afterwards refused his forgiveness for as Livy explains: “What remains of a woman after she has lost her honor?” And with a knife she stabbed herself in the chest.

The indignation this ignoble act of violation provoked before social order as well as before the laws of hospitality became the motive for the expulsion of the Etruscan monarch from Rome and subsequent founding of Democracy (509 BC).

In Renaissance art images of Lucretia’s suicide became the popular symbol of wifely chastity and consisted in a subject of painting that was purchased for the occasion of a wedding.[iii]

The composition of this painting was sagely conceived. It is not only in the eyes that we see Lucretia’s terror but also in the spasm of her body as perceived in the fingers of her right hand that are set off by the darkness like an expression of despair while the other hand tries to fend off her aggressor.

The violence of Tarquin is reflected in everything. In his stare, in the glint of the brandishing blade, in the blood-red of his garments. The sentiment of tumult is conveyed by the interplay of light and shadow in the folds of the drapery in the upper left that transmit their palpitation to the bed linens in the lower part of the canvas. Extremely indicative is the position of Tarquin’s legs that lunge into Lucretia’s private parts.

The multiple intersecting lines contribute to the sensation of violence traced by the bodies and limbs of the protagonists that run across the surface of the work.

Likewise, the triangle formed by the hand of Tarquin that holds the dagger and that of Lucretia who attempts to drive him back along with the legs of Tarquin and the body of his victim all direct the gaze of the viewer to Lucretia’s face with the result that the action of the image culminates in her countenance.

Moreover, the painting consists in two different sections. In one we have the luminous body of Lucretia coupled with the spotless white sheets of the chaste marital bed which portend the law of Democratic order in contrast with the murky section which is locus of violence and impulsion. The meaning of the work seems unambiguous. It is a message of conjugal honor and moral integrity.

But what holds our fascination?

When I try to analyze my own feelings, a suspicion comes over me that when I’m looking at a work by Titian what exerts a greater power of attraction over me is not the fact that virtue is extolled, in other words the content of the painting, its meaning but to the contrary the actual painterly treatment of the work, the pleasure of the colors, the evocativeness of the materials which indicates a potentially different orientation from that of a moral lesson, as if there were a shifting of interest towards the obscure parts, towards the realm of instincts and the archaic dimension of the human psyche.

It is only natural then that the very substance of the work, the corporality of the painting, the physical application of the material leads more to delectation than any ethical instruction.

Titian’s painting like more generally the painting of the Venetian School of the 16th century, is an art that organizes the painterly surface in smudges, blots of paint, abandoning contours. It is a painterly approach that appeals less to the intellect and more to the irrational side in such a unique way as to arouse us emotionally.

It is no coincidence that Jacopo Negretti known as Palma il Giovane, one of Titian’s last and most loyal students who watched him paint, said: “[And] if he discovered anything that did not fully conform to his intentions he would treat his picture like a good surgeon would his patient…[In] the last stages he painted more with his fingers than his brushes.”[iv] “Like God who sculpted man” which means that it is possible we may also have the fingerprints of Titian in his works.

Therefore, we might say that before he decided on a subject, before becoming Aphrodite or the Pope, his painting became the locus where the triumphant introduction of the tactile in art transpired. In this way, once again the question of how to approach a painting is posed.

The insights of Delacroix in his study on Michelangelo are extremely illuminating. Referring to the latter’s allegorical figures on the Medici tombs of San Lorenzo, Dawn and Dusk, Day and Night Delacroix writes: “I still cannot believe Michelangelo gave much importance to their ‘meaning’ and maybe he didn’t give them any until he finished them and placed them on the tombs…. What is essential to sculpture is form…. For that matter I would have had a bad opinion of him who before those formidable statues thought only of informing himself as to what those figures were trying to say,”[v] that is what do they signify, what are they supposed to tell us.

If we want to understand a work in its true dimensions we must resituate ourselves before it with the words of Delacroix in mind.

There is a paradox inherent in the work of Titian. On one hand the avowed intention that is understood after the initial logical reading of the work. On the other hand, the unconfessed intent which is the most essential. The former we trace back to Livy’s History of Rome. For the latter we abandon ourselves to the vibration of color and to the passion of the materials.

Because in our culture pleasure is associated with guilt and regret, perhaps among the reasons why the ethical grandeur of this work is praised is the need for an “alibi” that would remove the guilt attached to delight. Moreover, I might hazard the hypothesis that maybe this painting along with its entire epoch, by respecting conventions, that is always having a meaning or a moral to put in front as a pretext, makes the function of “straight” or “pure” painting more unrestrained, as such allowing it to operate beneath the surface. The pleasure is great because it is not named. In this way painting no longer has any need to justify itself and can exist without needing to produce proof of its legitimacy.

There is a similar version of the painting at Cambridge that originally gave rise to some doubts but it is now considered an authentic Titian and is housed at the Musée des Beaux-Arts of Bordeaux (Figure 2).

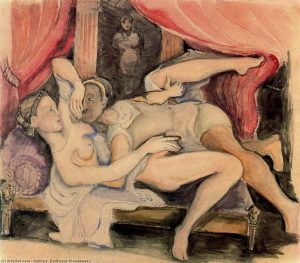

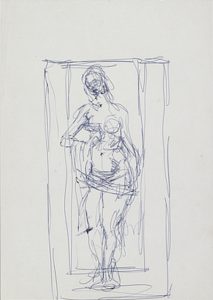

There are innumerable other works by painters inspired by the story of Tarquin and Lucretia. Some draw inspiration from the violation scene like the painting by Tintoretto (Figure 3) with the extraordinarily sensual body of Lucretia, Rubens (Figure 4), Palma il Giovane (Figure 5) extending all the way to Balthus (Figure 6). Others focus on the instance of Lucretia’s suicide who according to Livy declared: “Yet my body only has been violated; my heart is guiltless, as death shall be my witness.” We have two exceptionally penetrating works by Rembrandt (Figure 7 and Figure 8), one by Artemis Gentileschi (Figure 9) that is rather ambiguous in its approach. Panel paintings by Albrecht Dϋrer (Figure 10) as well as by Lucas Cranach (Figure 11) not to mention a sketch by Giacometti (Figure 12). The prolific number of works dedicated to the theme and the many different approaches they represent enlighten us as to the portent of the myth of Lucretia as well as to what is the most profound essence of painting.

- Figure 3: Tintoretto, Tarquin and Lucretia, ca. 1580, 175 x 152 cm, The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago.

- Figure 4: Peter Paul Rubens, Tarquinius and Lucretia, ca. 1608, 187 x 214 cm, The State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg.

- Figure 5: Palma il Giovane, Tarquin and Lucretia, ca. 1595-1600, 119 x 183 cm, Museumslandschaft Hessen, Kassel.

- Figure 6: Balthus, Lucrecia y Tarquino, watercolor, ca. 1952.

- Figure 7: Rembrandt, Lucretia, 1664, 120 x 101 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

- Figure 8: Rembrandt, Lucretia, 1666, 110 x 92.3 cm, Minneapolis Institute of Art.

It occurs to me while looking at Titian’s painting again that someone whose sensibility would more readily trust in the plastic elements of the work (color in and of itself, form and materiality), and who would therefore be naturally less interested in the narrative accuracy and the faithfulness of factual elements (moreover just as the painter himself proves to be by dressing an Etruscan prince in the clothes of a Venetian nobleman) could easily see this work transform into the vehicle for other myths where we might find in the place of Tarquin an Othello or something similar.

I think that the work of Titian serves the myth precisely because it transcends it, because it does not get consumed by it. The painting serves it faithfully because it extends it.

English translation by Andrea Schroth

- Figure 9: Artemisia Gentileschi, Lucretia, ca. 1593, 133 x 106 cm, Dorotheum.

- Figure 10: Albrecht Dürer, The Suicide of Lucretia, 1518, 168 x 74.8 cm, Alte Pinakothek, Munich.

- Figure 11: Lucas Cranach the Elder, The Suicide of Lucretia, 1529, 74.9 x 54 cm, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

- Figure 12: Alberto Giacometti, Lucretia, ca. 1960, drawing after Dürer,29.5 x 21 cm, Fondation Giacometti, Paris.

NOTES

[i] The date of Titian’s birth remains uncertain however we do know he died on the 27 August 1576. See Erwin Panofsky, Titien: Questions d’Iconographie, Bibliothèque Hazan, 2009, p. 12.

[ii] Livy [Titus Livius], The History of Rome, Book I, Chapter 58, lines 7-8, Perseus Project – Tufts University, English translation by Harvard University Press, 1919, p. 205.

[iii] Titien, Tintoret, Veronese: Rivalités à Venise, Hazan – Musée du Louvre Éditions, 2009, “La Femme en péril”, p. 318.

[iv] The Triumverate: Titian, Veronese, and Tintoretto, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, pdf, pp. 17-18.

[v] Delacroix, Écrits sur l’art (Michel-Ange), Librairie Séguier, 1988, p. 111 [English translation is ours].

![Hang ’Em High (1968) [Κρεμάστε τους ψηλά] <br/>Αυστηρότητα και επιείκεια ως στοιχεία <br/>της θετικής γενικής πρόληψης](https://theartofcrime.gr/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/morozinis_cover_nov21-237x143.jpg)