1. Nicolas Poussin, The Massacre of the Innocents, Musée Condé, Château de Chantilly.

Nicolas Poussin’s painting titled Le Massacre des Innocents [“The Massacre of the Innocents”] (Fig. 1) is held at the Musée Condé in the Chateau of Chantilly. It is 147 cm tall and 171 cm wide. The subject comes from the Gospel of Saint Mathew and evokes the slaughter of boy babies under the age of two in Bethlehem that was decreed by Herod the King of Judaea with the intent of securing his hold on power from all threats, notably that of his rival, the baby Jesus, whom he feared would one day seize his kingdom. The episode in question appears in Matthew 2:16-18 and reads as follows: "Then Herod, when he saw that he was mocked of the wise men, was exceeding wroth, and sent forth, and slew all the children that were in Bethlehem, and in all the coasts thereof, from two years old and under, according to the time which he had diligently inquired of the wise men. Then was fulfilled that which was spoken by Jeremiah the prophet, saying, In Rama was there a voice heard, lamentation, and weeping, and great mourning, Rachel weeping for her children, and would not be comforted, because they are not."* [King James Version]

He painted it in Rome during the first years of his stay there; however, opinion varies as to the exact chronology, wavering between 1625-26 until 1632. The work was commissioned by Vincenzo Giustiniani and initially remained in Rome, at the Palazzo Giustiniani, in a hall where nine other paintings were on display, including works by Guido Reni and Joachim von Sandrart. Some of those works were hung above doors, including Poussin’s composition that measured 2.30 m from the ground. In 1804 it was purchased by Napoleon’s brother Lucien Bonaparte during the French occupation of Rome. Upon the fall of the Empire, the painting found itself in the hands of a merchant in London from whom it was acquired in 1854 by the son of King Louis-Philippe, the Duke of Aumale, who was living in exile in England at the time. After returning to France, he came up with the idea in 1889 of converting his tower at the Château de Chantilly into a museum which would be opened to the public after his death. Moreover, already in 1886, he bequeathed his estate and his collections to the Institut de France (the French Academy). In accordance with the stipulations of his donation, the works had to be exhibited without altering in the least the manner in which they were originally presented. Likewise, it was also forbidden to loan them to temporary exhibitions.[1]

The reason why this fabulously rich banker born in Chios in 1564, patron of the arts and collector of works by Caravaggio, among others, commissioned the present work was due to an event in the history of the Giustiniani family that held sway over the island of Chios for 220 years, from 1347 to 1566, the year of the Ottoman conquest of Chios. The painting in question was meant to memorialize the tragic fate of the family’s children who were held hostage, tortured and ultimately murdered. In the History of the Giustiniani from Genova we read: “On the 14th of April 1566 a powerful fleet of 80 galleys under the command of Ottoman Grand Admiral / Kapudan Pasha Piali or Piali Pasha (or Paoli, according to other sources) essentially succeeded in occupying the port of Chios without waging battle thanks to a stratagem. In reality, the Ottomans asked to moor in the capacity of friends; however, as soon as they berthed, they summoned the head of the Maona,[2] the podesta or chief magistrate, Vincenzo Giustiniani (apparent ancestor), and his twelve governors then proceeded to imprison them. This did not prevent the island from being violently sacked, the churches were destroyed or transformed into mosques. Very swiftly, all that was beautiful, functional and useful on the island was either plundered or savaged. Vincenzo Giustiniani, three governors and all of the most prominent Giustiniani males were shipped off to Constantinople. The youngest of the line, those under the age of twelve, were locked up in a monastery dedicated to Saint John the Baptist. Twenty-one boys between the ages of 12 and 16 were separated from their parents, forced to renounce their Catholic faith and conscripted into the Janissary corps [elite military guards of the Ottoman Empire]. Three of the captives succumbed to the will of the Ottomans, were circumcised but afterwards managed to escape to Genoa where they once more embraced their ancestral faith. The other eighteen boys were murdered after atrocious tortures on September 6, 1566. The church proclaimed them saints.” [3] There is a painting by Francesco Solimena from 1715 with the title “The Massacre of the Giustiniani at Chios” that evokes these events (Fig. 2). It is a multifaceted and majestic work.

2. Francesco Solimena, The Massacre of the Giustiniani at Chios,

Museo Nazionale de Capodimonte, Naples.

3. Domenico Ghirlandaio, The Massacre of the Innocents, Santa Maria Novella, Florence.

4. Jacopo Tintoretto, The Massacre of the Innocents, Scuola Grande di San Rocco, Venice.

5. Pierre Paul Rubens, The Massacre of the Innocents, The Thomson Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario.

6. Guido Reni, The Massacre of the Innocents, Pinacoteca Nazionale di Bologna, Bologna.

The painting by Poussin makes a strong impression in a very different way – through the austerity and restraint with which he treated this subject in spite of its emotional charge stemming from the Gospel of Matthew and the slaying of the Giustiniani family. It is remarkable that this work that Francis Bacon qualified as “the best human cry in painting” is a composition in which geometry reigns. It has something of the simplicity and the force of ancient Greek sculpture that Poussin himself had the chance to study in Rome, at the city’s sumptuous collections of works from Greek and Roman Antiquity. It is noteworthy that Poussin painted forms with such austerity in this city while the Baroque style was flourishing. This work consists in an important lesson that functions like Greek tragedy as it has condensed all the intensity but also all the action into the least possible components. It is interesting to compare this composition with its counterparts by Ghirlandaio (1486-90) (Fig. 3), by Tintoretto (1582-1587) (Fig. 4), by Rubens (1611-1612) (Fig. 5) and by Guido Reni (1611) (Fig. 6) – works that are extremely complex and dramatic in nature, in contrast to Poussin’s canvas that concentrates on four central figures in the foreground and three more in the background.

This painting teaches us that pathos does not express itself with pathos, but rather with the distance we take from it. An expert on the work of Poussin, Anthony Blunt, gives us an excellent explanation of how his painting works: “His pursuit of a rational form in art was so passionate that it led him in his later years to a beauty beyond reason; his desire to contain emotion within its strictest limits caused him to express it in its most concentrated form; his determination to efface himself, and to seek nothing but the form perfectly appropriate to his theme, led him to create paintings which, though impersonal, are also deeply emotional and, although rational in their principles, are almost mystical in the impression that they convey.”[4]

Poussin himself in a letter to Paul Fréart de Chantelou speaks of his natural inclination towards discipline: “My character makes me seek out and love things that are well-organized avoiding disorder that is as contrary and hostile to my nature as light is to obscure darkness.”[5] Chantelou points out that Bernini said the following of Poussin: “Mister Poussin is a painter who works from here”, pointing to his forehead.[6] Concerning the emphasis Poussin put on simplicity and clarity of expression, we have the testimony of Abbey Bordelon that informs us: “To an important man who loved painting, having shown Poussin one of his works, this outstanding artist said: “Sir, in order to become skilful all you need is a little poverty.”[7]

However, all this does not mean that Poussin was unfeeling or that he was not emotionally invested in the work he painted. It is worth reading what he wrote to another painter, Jacques Stella, in 1646 – an excerpt that allows us to form a more complete picture of his personality: “No longer do I have enough joy or health to commit myself to sorrowful subjects. The Crucifixion made me ill, it caused me terrible pain. […] I would be unable to resist the distressing and serious thoughts with which one must fill the spirit and heart to successfully render those subjects that are in and of themselves so doleful and bleak. I beseech you to reieve me of them.”[8]

The mother’s face in this work is so close in spirit to ancient Greek art, the abstraction with which he painted it is so predominant that certain specialists speculated that there may have been a prototype for it, a real Ancient Greek tragic mask, or prosopon. Although an identification was not possible, a kinship with the spirit of tragedy is obvious. And I believe that if this work could be elevated to the status of a symbol, of “the best human cry,” it is precisely because of this achievement of reduction and condensation.

It is interesting to observe that all the elements of the painting are integrated into geometric shapes. It has been pointed out for example how the mother’s arm and the hand of the soldier who holds her by her hair are inscribed in a kind of ellipsis. Two folds in the woman’s clothing stand out because they catch the light which helps the eye of the viewer travel from the infant’s body towards the leg, torso and bent arm of the woman wearing blue garments. There is a somewhat constricted second ellipsis that contains the first and overlaps with it in various places; it is delimited by the hand of the soldier who lifts his sword, the illuminated hand of the central female figure, the folds in the blue dress and raised elbow of the second woman as well as the upper part of the soldier’s red tunic.

As we remarked earlier, contrary to other painters who treated the same subject in a totally different manner, here Poussin limits himself to very few figures: the infant fallen to the ground who already has a wound in his side; the solider wielding a sword; the mother who tries to shield her baby and drive away the attacker; the woman with the blue robe who carries a dead child with her other arm raised in a gesture of despair; and another woman who tries to flee while two more are discernible between the legs of the soldier. We have the impression that the woman in blue holding the dead baby is ready to exit the scene because everything has ended for her, while the other at the center of the composition is battling fiercely. In this work the painter, with the appropriate lighting, leads the gaze of the viewer to the main points of action: the fallen infant whom the soldier stomps on with his foot, the mother’s arm as she tries to repel the soldier, and the latter’s hand as he shoves her back.

The face/mask of the mother is found at the intersection of two diagonals traversing the canvas. One starts at the head of the infant, passes over the face of the screaming woman and continues through the head of the woman dressed in blue. The other diagonal crosses the body of the central figure as well as the soldier’s body. What one notes here is that the drama unfolds beneath a bright blue sky. We would expect a tempestuous backdrop with subject matter of this sort. However, in its indifference, the azure expanse becomes crueller and the drama more piercing. After all, doesn’t art itself struggle against this same indifference, against the cosmic void of meaninglessness?

The biography Delacroix wrote about Poussin begins with the following thought: “Poussin’s life is reflected in his works.”[9] Therefore, it would be useful, to better enter the spirit of the painting, to consider how Poussin lived and worked. One of his biographers, Bellori, offers us an image of a Stoic philosopher in the following description: “He had an extremely organized lifestyle, contrary to all those who paint on impulse for a spell with much fervor, then they get tired out and abandon their brushes for a prolonged period. As for Nicolas, it was his custom to awake early and take a walk for an hour or two around the city, but he would almost always go to the Trinità dei Monti on Mount Pincio, not far from his house [that we reach after a lovely brief incline with its trees and fountains and where we come upon a splendid view of Rome and its gracious hills] and there he would converse with his friends […] Upon returning home, he would immediately go to work and paint without interruption until midday. After his meal, he would go back to work for several hours. […] In the evening, he would go out again and walk around the foot of the same hill, in the square among the crowd of strangers who were in the habit of gathering there. […] Those who, aware of his fame, wished to see him and treat him as a friend, would find him there […] He was eager to listen to others, following which his own remarks were very serious and listened to attentively. His words and ideas were so well-adapted and well-ordered that they seemed meditated far in advance, rather than uttered extemporaneously.”[10]

Bellori refers to another incident that characterizes Poussin: “In his house he would not abide ostentatiousness, and he would take the same liberty with his friends, even those of high social standing. One day he received the visit in his studio of Monseigneur/Monsignor Camillo Massimi who is now cardinal and whom he greatly loved and respected for his noble qualities. With conversations and discussions, the evening progressed and when the time came for the cardinal to take his leave, Poussin accompanied him down the stairs to his carriage lighting their way with a lantern. Seeing him struggling with the light, Monseigneur/Monsignor remarked: ‘I pity you for not having a servant’. To which Poussin replied: ‘I pity Your Eminence more for having so many.”[11]

Of course, this is especially significant because Poussin was famous and extremely well-off, as his biographer Bellori informs us once again: “He never discussed the price of his paintings. When he delivered them, he marked the sum on the reverse side and the exact amount was sent to his home immediately, without any reduction whatsoever.”[12]

7. Pietro da Cortona, The Ceiling of the Palazzo Barberini, Rome.

8. Pietro da Cortona, The Allegory of Divine Providence and Barberini Power, Palazzo Barberini, Rome.

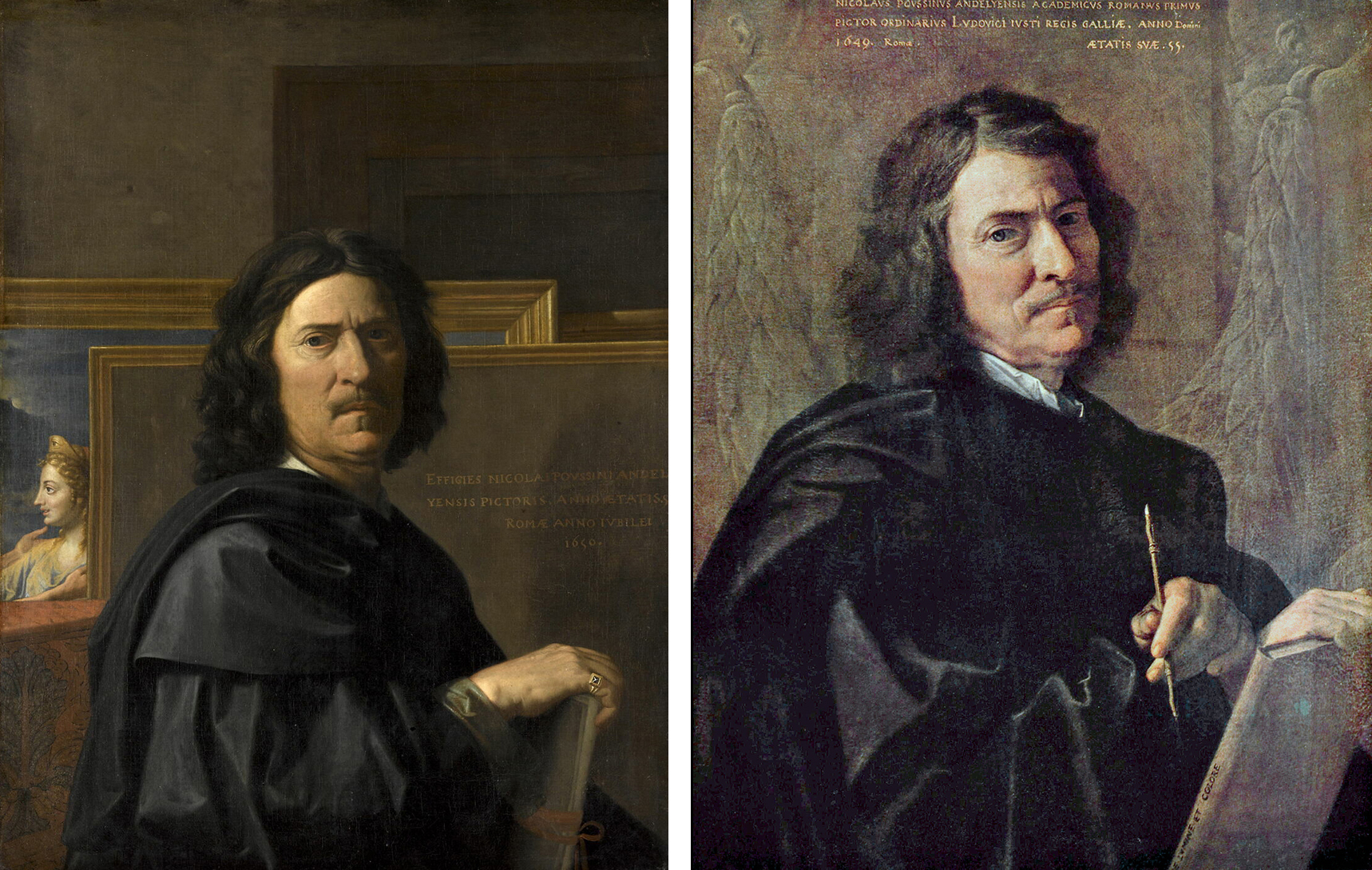

9. Nicolas Poussin, Self-Portraits

(1) Staatliche Museen, Berlin; (2) Musée du Louvre, Paris.

10. Nicolas Poussin, The Massacre of the Innocents, Petit Palais, Paris.

11. Nicolas Poussin, Preparatory drawing for the Massacre of the Innocents, Le Palais des Beaux-Arts de Lille, France.

12. The way in which the painter prepared the final version is of particular interest.

Poussin did not accept commissions for large-scale works, which was practically the rule for renowned painters of his era. Suffice it to consider as an example the ceiling of the Palazzo Barberini painted by Pietro da Cortona (Fig. 8). Poussin painted for a narrow circle of cultivated people who were involved with literature and the arts.

In my opinion, this puts him at closer proximity to the idea we have today of the painter for whom the work is not inspired by a commission, but from an inner need that possesses the painter in a process of personal completion. Furthermore, and this was also exceedingly rare for that period, he did not paint portraits. The only ones that have come down to us are two self-portraits (Fig. 9).

Poussin painted another work (Fig. 10) on the subject of the Massacre that is held in the museum of the Petit Palais in Paris, a completely different composition from the homonymous painting in the Chantilly museum.

The way in which the painter prepared the final version is of particular interest. We have a drawing, a preparatory study for the work housed in the Musée Condé, which is found at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Lille (Fig. 11). Aside from the drawings he made to study the lighting and more generally the composition of a work, Poussin modelled little figurines out of wax which he would then dress in very fine fabric in order to observe how the folds hung, then he would pose them according to the composition of the work over a surface. Next, he would cover the installation with a kind of box that he drilled a hole into to allow the light to enter and he would make a second opening to be able to see the overall picture. All his biographers refer to Poussin’s so-called “box”, or “grande machine” (‘great machine’), that resembled a toy theatre box. Sandrart evoked the process: (Fig. 12) “He would take a board and there he would stage little nude figurines made of wax, arranging them in the positions necessary for expressing the action of the whole scene. After which, to study the fall of the drapery, he would cover the figurines in wet paper or thin cloth… And from these maquettes (scale models) he would paint his canvas.”[13]

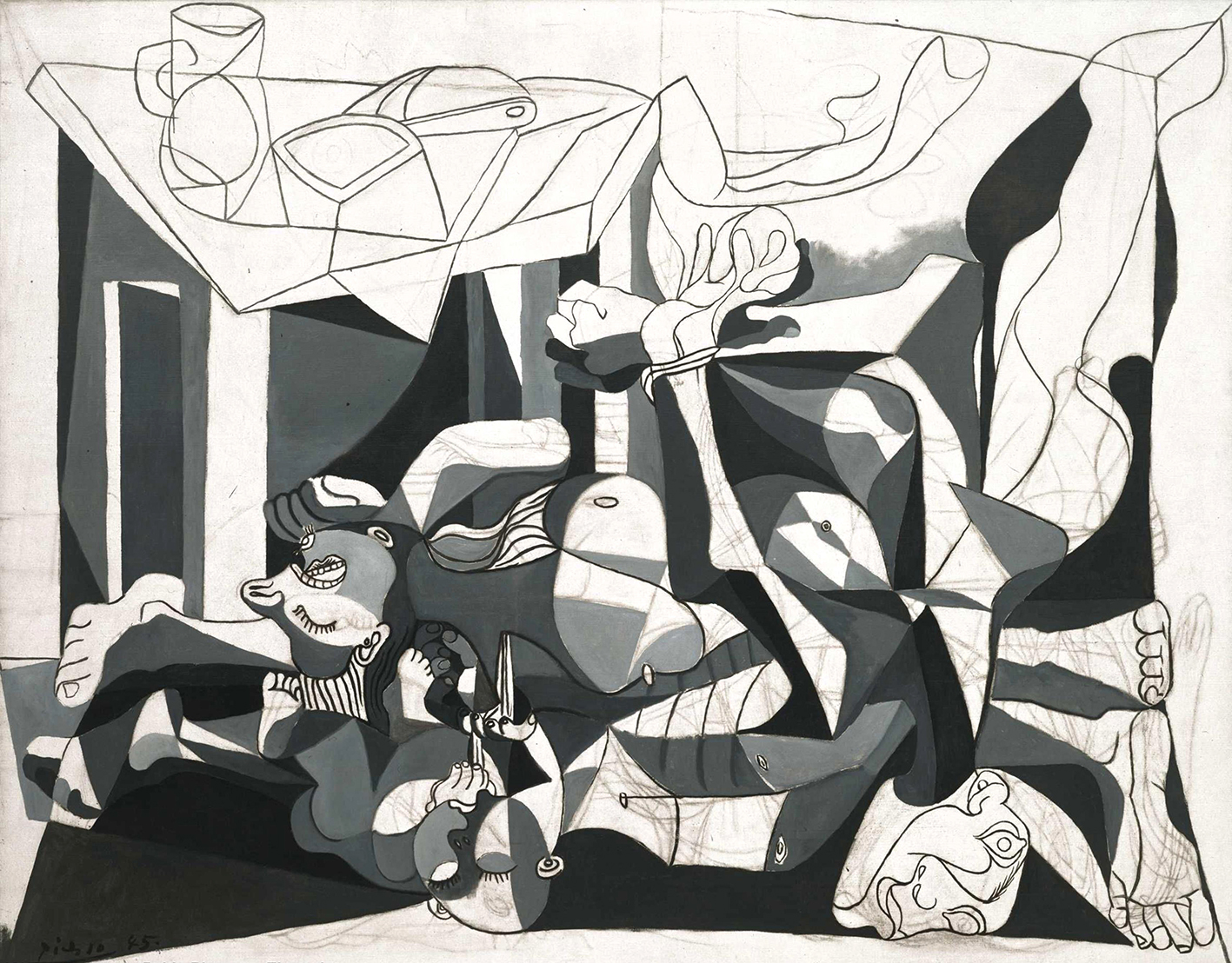

13. Pablo Picasso, El Osario [The Charnel House], Museum of Modern Art, New York.

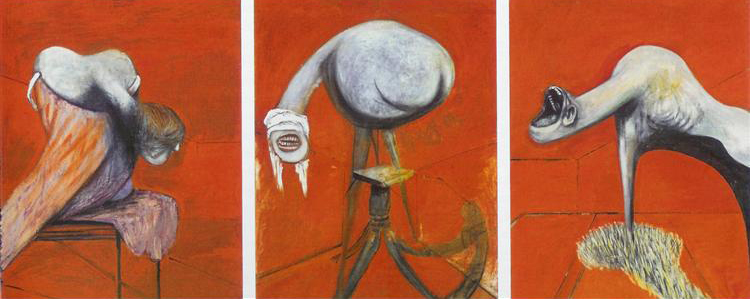

14. Francis Bacon, Three Studies for Figures at the Base of the Crucifixion, Tate Britain, London.

As this work was hung at the Palazzo Giustiniani high above a door, the painter took care that the viewer could see the figures from below upward, di sotto in sù (‘seen from below’), according to the technical term. This automatically places us, the spectators, like the infant under the soldier’s foot, in the position of victim, which results in the work becoming contemporary with the person viewing it every time. The abstract way he treated the subject gives the painting the capacity to allude to events and eras beyond the specific ones the painter drew inspiration from. Thus, every epoch can recognize its own face in this work. Contemplating Poussin’s painting, another infant comes to mind, lying dead on a beach in the Aegean Sea, as well as other innocent victims of today’s wars in the same regions as those described in the Gospel of St. Matthew, or someone who cries out “I can’t breathe” somewhere else.

Many contemporary artists drew inspiration from the Massacre of the Innocents by Poussin. When Francis Bacon was twenty, he lived near Chantilly working as a decorator and upon seeing this picture he declared, as mentioned above: “It’s probably the best human cry in painting. His cry made me think. I did hope one day to make the best painting of the human cry.”[14] An exhibition mounted in September of 2017 under the title “Poussin: Le Massacre des Innocents, Picasso, Bacon” had as its theme the eponymous painting by Poussin in conversation with works of our times, such as Picasso’s El osario [‘The Charnel House’] (1944-45) (Fig. 13) and Bacon’s Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion (1944) (Fig. 14), among others.[15]

Thus, the present painting expresses the violence every power exerts to ensure its survival, indifferent to the victims it leaves in its wake. It serves as a valuable lesson on what the relationship between a work of art and politics can and should be in order to transcend the concrete and endure over time.

English translation by Andrea Schroth

*"When Herod saw that he had been tricked by the wise men, he was infuriated, and he sent and killed all the children in and around Bethlehem who were two years old or under, according to the time that he had learned from the wise men. Then was fulfilled what had been spoken through the prophet Jeremiah: 'A voice was heard in Ramah, wailing and loud lamentation, Rachel weeping for her children, she refused to be consoled, because they are no more."

[New Revised Standard Version]

NOTES

[1] Château de Chantilly, https://chateau_de_Chantilly./ https://chateaudechantilly.fr

[2] The appellation ‘Maona,’ plural Maonenses, designated famous medieval joint stock companies that were founded by the Giustiniani family; see Chapter IV of Alexander Vlasto’s XIAKA or The History of the Island of Chios from its earliest times down to its destruction by the Turks in 1822 [the second part of this volume in two parts was translated by A. P. Ralli, A History of the Island of Chios A.D. 70-1822, London: Dryden Press, 1913].

[3] The History of the Giustiniani of Genoa, Italy: http://www.giustiniani.info/english.html.

[4] Athony Blunt, Nicolas Poussin, London: Pallas Athene, 1995, p. 7.

[5] Nicolas Poussin, Lettres et propos sur l’art, Letter dated 7 April 1642, Collection «Savoir», Hermann Éditeurs des sciences et des arts, p. 67.

[6] Op. cit., p. 200.

[7] Op. cit., p. 199.

[8] Op. cit., p.125.

[9] Eugène Delacroix, Écrits sur l’art, Paris: Librairie Séguier, 1988, p. 209.

[10] Bellori, Félibien, Passeri, Sandrart, Vies de Poussin, ed. Stefan Germer, Paris: Éditions Macula, 1994, p. 78

[11] Op. cit., p. 87.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Op. cit., p. 149.

[14] From the exhibition catalogue, Pierre Rosenberg, “Poussin: Le Massacre des Innocents, Picasso, Bacon,” Jeu de Paume du Domaine de Chantilly, Flammarion, 2017 [in English: Judith Benhamou Reports: “The Massacre of the Innocents: The Greatest Scream in the History of Painting. Poussin, Picasso and Bacon”, September 17, 2017].

[15] Exhibition titled “Poussin: Le Massacre des Innocents, Picasso, Bacon” held from September 11, 2017 until January 7, 2018 at the Jeu de Paume of the Domaine de Chantilly.

![Hang ’Em High (1968) [Κρεμάστε τους ψηλά] <br/>Αυστηρότητα και επιείκεια ως στοιχεία <br/>της θετικής γενικής πρόληψης](https://theartofcrime.gr/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/morozinis_cover_nov21-237x143.jpg)