...Suffering is one very long moment. We cannot divide it by seasons.

We can only record its moods, and chronicle their return. With us time itself does not progress.

It revolves. It seems to circle round one centre of pain…

For us there is only one season, the season of sorrow. The very sun and moon seem taken from us…

It is always twilight in one's cell, as it is always twilight in one's heart.

Oscar Wilde, De Profundis

In many countries in the world art and crafts projects are carried out in a large number of correctional institutions, where inmates get the opportunity to create works of art under the guidance of professional artists. It is generally believed that these efforts favorably impact inmates as well as the correctional institutions themselves. Art has been shown to promote empathy, understanding and a more sympathetic emotional insight into those disconnected with the realities of prison incarceration but equally, prisoners involved in artistic projects benefit from the fact that their existence is affirmed through creativity. Artworks made by prisoners circulating in the outside world affirm that they still exist, that they are still alive, that they are there. A wealth of publications exists on this subject in Europe, the UK and the US. In 2006 a study appeared in the UK as the second element of a three-part research plan, designed to strengthen the evidence base for the arts as an effective medium in offender rehabilitation. It was commissioned by the Arts Council England, the Department for Culture, Media and Sport and the Offenders’ Learning and Skills Unit at the Department for Education and Skills.[1] “The Prison Arts Resource Project” of 2014 is an extensive annotated bibliography of evidence-based studies evaluating the impact of arts programs in 48 U.S. correctional settings.[2] Another American research paper is “The Impact of Prison Arts Programs on Inmate Attitudes and Behavior: A Quantitative Evaluation” of 2014.[3] The article “The Rehabilitative Role of Arts Education in Prison: Accommodation or Enlightenment?” examines competing discourses of penal educational provision in order to assess the role of the arts. A second part examines a radical educational agenda of inclusion based on emancipatory theory, as a conduit for personal transformation, in which the creative arts have a central role.[4] A recent study is “European Prison Arts,” which appeared in spring of 2020 and contains a research into the impact of arts in European prisons.[5]

In the UK the National Criminal Justice Arts Alliance aims at utilizing the arts within the criminal justice system as an incentive for change. It represents “a network of over 900 individuals and organisations that deliver creative interventions to support people in prison, on probation and in the community.” It provides a network and a voice for talented and creative people, committed to work with people in the criminal justice system.[6]

Museums and art galleries have also been have paying attention to the relationship between art and its assumed humanitarian influence on incarceration and penitentiary institutions. In 2019 the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in Connecticut organised an exhibition affirmatively titled How Art Changed the Prison. It comprised artworks made by inmates of Connecticut’s correctional institutions over the previous three decades, organised by the Community Partners in Action (CPA), a non-profit organisation aiming at instigating the behavioural change of inmates, using visual art as a tool.[7] Another organisation with a comparable goal is the Justice Arts Coalition (JAC), which unites artists with currently and formerly incarcerated artists. The JAC acts from the belief in the transformative power of the arts to enhance justice.[8]

In addition to the work taking place in prisons with inmates, there are numerous examples of socially engaged contemporary artists who explore the criminal justice system, particularly in the United States, which has the highest incarceration rate in the world and is tainted by structural racism, with a disproportionately high number of African American prisoners. As Michelle Alexander, author of The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, has pointed out, more African American adults are in prison or jail, on probation or parole— than were enslaved in 1850, before outbreak of the Civil War began. This has led to the massive increase in prison construction in the US. In 2018/19 The Contemporary Arts Museum Houston (CAMH) presented Walls Turned Sideways: Artists Confront the Justice System, the largest and most comprehensive museum presentation on the subject through the eyes of more than thirty artists, with works spanning the past forty years. The exhibition features work by artists from across the US that addresses the broken criminal justice system in the country (with its systemic racial inequality), mass incarceration, and the prison-industrial complex. Representing a range of contemporary art production made both in the studio and in the social realm - some deploying direct action working inside, with inmates - the exhibition includes artworks that take social justice issues as a subject matter and institutional critique of the prison and court systems as structures for dismantling and reform. The artworks in the exhibition provide insight into to offenses within the justice system and the inequalities inherent therein. The title of the exhibition Walls Turned Sideways comes from a quote by the now legendary political activist, academic, black feminist and author, Angela Davis (b. 1944): “Walls turned sideways are bridges.” The exhibition was staged in order to function as a connecting conduit for encouraging conversation, engaging in contemplation, and inspiring change.

Some notable examples of artworks in the exhibition include Josh Begley’s Prison Map project (2012), which takes the scale of the prison industrial complex in the US as its focal point. There are over two million people behind bars in the United States. Staggeringly, there are more jails and prisons in the country than colleges and universities. Nevertheless, because so many of these facilities are hidden from view – safely ‘out of sight, out of mind’ - located in rural areas and remote locations, it is quite difficult to grasp the enormity of the scale of the US prison industrial complex. Begley's Prison Map project comprises more than 5,300 aerial images that give an idea of the expanse and enormity of the American prison system, and its architecture of incarceration, also termed carceral architecture. Prison Map is, in the artist’s words “about visualizing carceral space” but also about providing insight into the ubiquity, isolation and size of the American prison system. Titus Kaphar’s The Jerome Project (2014) also engages with the criminal justice system. The artist’s father served prison time so in 2011 Kaphar began searching for his prison records. When researching the project, he found dozens of men who shared his father’s first name, Jerome, and last name. He subsequently created portraits of each Jerome, based on their mug shots, on flat gold-leaf backgrounds, partially submerged in tar. Although each work depicts an individual, it alludes to a community of people, African American men, who are overwhelmingly overrepresented in the prison population. The works make reference to the visual tradition of Byzantine icons, and specifically Saint Jerome, an allusion to the notion of forgiveness of past transgressions, which lies at the heart of Christian religion, as well as others. Kaphar considers the inability to offer forgiveness as one of the shortcomings of the current criminal justice system. The black tar – which covers their mouths or faces - refers to the silencing of incarcerated men, who are stripped of their rights, including the right to vote and access to federally funded programs. It also makes reference to the ‘blacking out’, or cancellation of ones being inside the prison system, but also – on the other hand – affords them a kind of privacy they do not otherwise have on mug shot websites, which are publicly accessible.

Titus Kaphar, The Jerome Project

Jerome I-V, 2014. Oil, gold leaf and tar on wood panel 7 × 10 ½ in.

Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

The prison experience is rendered in a different manner, by means of photography, in the work of Keith Calhoun and Chandra McCormick. For more than thirty years, they have been documenting life in the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola, a prison situated on the land of several former cotton and sugarcane plantations. It is known as Angola, as that was the country of origin for many of the slaves working there. Comprising a massive total of 18,000 acres, an area bigger than Manhattan, it is also the largest maximum-security prison in the United States. It is also known as the “The Farm” because it continues to grow cash crops, using inmate labor – another kind of involuntary servitude, which is prohibited by the US Constitution, except for convicted inmates. Thus a dark history of subjugation continues in a different shape. There are more than six thousand inmates in the prison, three quarters of which are African American. Calhoun and McCormick’s photographs include moments inside the prison, on the fields, but also outside, during short-lived bittersweet reunions of inmates with relatives for events such as funerals. These photographs are not marked by anger, rancour or pity but rather they are pervaded by a sense of warmth and humility which prompts one to truly consider the circumstances of those portrayed, to glimpse an essence of their full humanity and their individuality as individual human beings. The series shines a light on important issues such as blind justice, bias, structural racism, unsavoury labour practices, and the social fall-out of incarceration, whilst restoring visibility to a community that is invisible to the public at large. It exposed the deficiencies of the US criminal justice system and gave visibility to an often forgotten population.[9]

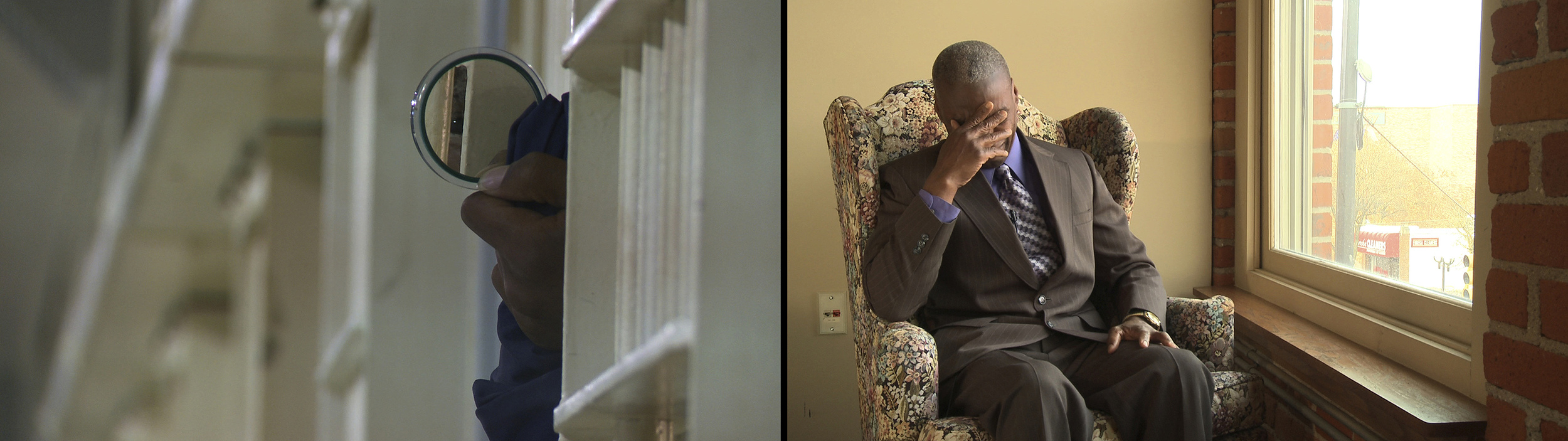

One of the most heart-wrenching works in the exhibition is Tirtza Even’s film, installation and interactive online archive, Natural Life (2014-15), which exposes the inequities in the U.S. juvenile justice system by recounting the stories of five men and women who were sentenced to life imprisonment for crimes they committed as youngsters. The US is the only country in the world that sentences children to life imprisonment without parole, for crimes they committed while they were in school, and before they could drive, or vote. This is a practice known also known as “natural life,” hence the title of the film. These individuals are thus condemned to die in prison, without being entitled to parole. The stories are presented, through documentation and reenactment (recorded conversations with the inmates, interviews with their families, victims of their crimes, police officers, lawyers, civil rights attorneys, juvenile justice experts, community members) against the complex contexts of social bias, traumatic family relations, neglect, violence, mistreatment and alienation. Many of the juveniles sentenced to natural life in the US did not commit homicide themselves, but were convicted for taking orders from adult perpetrators or masterminds, or were acting as lookouts, as is the case for three of the subjects in Even’s film. Others were driven to crime by despair and disenfranchisement. The strength of the project lies in the fact that it is told from multiple angles, from people of varying age, gender, economic background and race. It presents conflicting or differing views in which it becomes clear that truth cannot always be proved solely through process and facts, reminding us, finally, how important rehabilitation should be within the justice system, especially for young people with their whole life ahead of them. Cook County Jail is the largest single-site jail in the United States, occupying 96 acres of land—more than eight city blocks—next to Chicago’s Little Village neighborhood. It admits approximately 100,000 pre-trial detainees each year, with an average daily population of 9,000; more than half of these inmates come from the residential areas surrounding the facility.

Tirtza Even, Natural Life (2014-2015)

Still image from Natural Life; Reenactments in prison cell shot at an abandoned prison in Jackson, Michigan. On the right: Donnie Logan, who served a life without parole sentence since age 15; was commuted by the Governor at age 55.

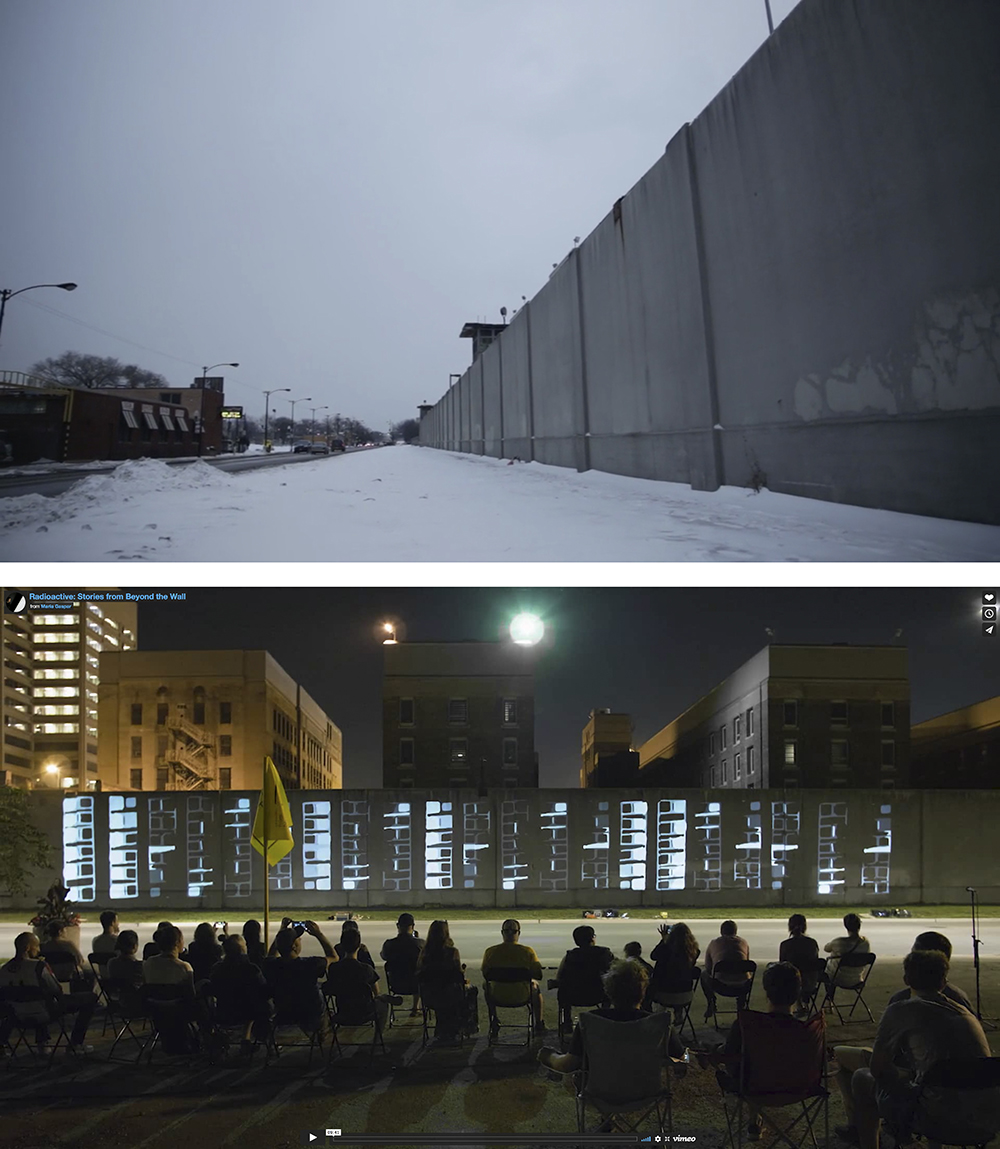

On the other hand, projects like Maria Gaspar’s 96 Acres Project [10](began 2012) addresses the impact of prison presence within a community, with the same prison complex as its point of departure. The project consists of a series of community-engaged, site-responsive art projects that address the impact of the massive Cook County Jail on Chicago’s West Side. Unlike many jails, which are in far-out locations or rural areas, Cook County Jail is right next to Chicago’s Little Village neighborhood, at a stone’s throw from residential and commercial buildings. The jail’s 25-foot-tall northern wall directly faces a row of single-family homes. In an attempt to assess the impact of this mammoth, foreboding institution on the surrounding community, Maria Gaspar - who is a Chicago-based artist and Little Village resident - gathered together artists, educators, activists, formerly and currently incarcerated people, young people, and jail personnel in order to generate conversations about power, change, space and community. The 96 Acres Project project has taken many forms, including an oral history archive, videos projected on the jail wall, sound installations for outdoor space and the production of fanzines. Its inclusive, creative character, founded on dialogue and exchange, community based practices and collective artworks attempts to challenge and reimagine the intimidating, oppressive spatial narrative represented by the jail. At the same time, it attempts to shed light on what is hidden within and to engender narratives of empathy. A later project by the artist, entitled Radioactive: Stories from Beyond the Wall (2018) consisted of a series of radio/visual broadcasts situated between the Cook County Jail, and the adjacent working-class residential area. As part of the project, the jail’s massive the North-side become a screen for audio and video created by past and present detainees, and for giving voice from those on the inside to those on the outside.

The processes that result in incarceration do not only affect those inside prisons, but a host of people outside from the families and friends of perpetrators to the families and friends of those who lost loved ones to heinous crimes, creating an often invisible trail of trauma. Sonja Henderson’s Harbor for Mending Hearts (2019) is a tent-like space made of quilts, sewed by mothers who lost children to police brutality, street or drug violence, among other things. Each woman made a square, using collage, mixed media and quilting techniques to tell the story of their child’s death but also to highlight their qualities, importance, accomplishments and dreams. The project is a good example of how art can help in healing processes, helping the women to literally “stitch” their lives back together. The sewing circles organized by the artist to produce the work gave the mothers the opportunity to express and process their grief through a creative process. As Henderson herself says, ““These women have expressed to me that it’s important to be able to vocalize how they feel about their child, and who their child was, beyond how possibly the media may have portrayed him, even beyond their own family household.”[11]

A notable example of attempting to generate insight into prison conditions is a work by Andrea Fraser, one of the most astute commentators on racial politics and institutional critique, particularly in the United States, her country of origin. In her sound installation Down the River (2016), made for the Whitney Museum’s new $420.000.000 building built by star architect Renzo Piano, Fraser links two seemingly unconnected phenomena, the rise of prison construction in the last fifty years and the recent explosion and building boom of (mostly privately funded) museums in the US. “Art museums and prisons can be seen as two sides of the same coin in an increasingly polarised society where our public lives, and the institutions that define them, are sharply divided by race, class, and geography,” Fraser writes. Her site-specific project at the Whitney, which leaves the entire fifth floor of the museum empty, and plays audio she recorded at Sing Sing Correctional Facility, a maximum-security prison. One can hear voices of inmates, instructions being called out over an intercom, cell doors sliding open and closed, and all kinds of sounds generated by the architecture of confinement. The work attempts to bridge an unfathomable social divide. Sing Sing’s inmates are not only persons that have been penalized by the criminal justice system, but have also been economically excluded from the nation’s job market. The Whitney Museum, by extreme contrast, is emblematic of the control that America’s ultra-wealthy exert one these private institutions and the fact that they cater to the socially upwardly mobile (a ticket costs $22, hardly affordable for economically disenfranchised families), while reinforcing the status, promoting the tastes and securing the tax advantages of the global 1%. As the artist herself says of the work, “I am bringing the sounds of Sing Sing to the Whitney’s fifth floor to link art museums and prisons; they are two sides of the same coin of inequality.”

An important contribution of contemporary artistic practice that engages with the criminal justice system is that it proffers much-needed alternative narratives, different to the stereotypical ones that casts prisoners as dehumanised, threatening ‘Others’. As a subject, perceptions of prisoners are governed by a bias that often denies them their humanity, and portrays them as less-than-human, indeed sometimes – according to the severity of the crimes committed – as inhuman or sub-human. This image has been cultivated and is profoundly influenced by Hollywood movies and TV series, which created a specific and predominantly one-sided picture of a world that most of us don’t know from experience. Thinking of so-called ‘jailbirds’ we might recall the voice of Johnny Cash, singing at Folsom State Prison; or we may remember Andy Warhol’s 1964 screen print “Electric Chair,” which is engraved in our collective memory as an iconic image of an apparatus of capital punishment, in which the human is absent, though it is intended for human use. Another example is the American artist Lucinda Devlin, who in 1991 made the similarly chilling Omega Suites, a series of photographs of electric chairs, final holding cells, executioner's rooms, lethal injection chambers, gallows, gas chambers and witness rooms. She captured the almost sterile atmosphere of prison interiors in a clinical but also arresting and penetrating way. Her pictures draw our attention, in an unforgiving manner, to the cold and inhumane character of the American justice system through the enforcement of the death penalty. Twenty-five states, including, Kansas, Indiana, Virginia and Texas still have the death penalty, with the law in force in areas all over the country. (Four others, Colorado, Pennsylvania, California and neighbouring state Oregon have Governor imposed moratorium, which is a suspension of a law until it is deemed worthy again). Characteristically, in both works the human subject is absent, indicating the erasure of the prisoner as subject, but also focusing on the mechanics of carceral architecture.

Lucinda Devlin, The Omega Suites

1. Witness Room, Broad River Correctional Facility, Columbia, SC 1991

2.Electric Chair, Broad River Correctional Facility, Columbia, SC 1991

3.Electric Chair, Holman Unit, Atmore, AL 1991

4.Gas Chamber, Maryland State Penitentiary, Baltimore, MD 1991

Socially and politically engaged art is often seen as a vehicle for social change. It proffers alternative narratives, mines little known or deliberately marginalised histories and offers correctional readings of issues that often suffer from stereotypical, polarised or prejudiced representations, especially in the media. It can also give voice to the politically or socially disenfranchised.[12] Taryn Simon’s The Innocents (2002), for example, documents the stories of individuals who served time in prison for violent crimes they did not commit, wrongful convictions predominantly based on mistaken identification. The series looks into this miscarriage of justice by tracing the people who were victims and photographing them at the site of the alleged crime or the scene of the arrest. The portraits are arresting, poignant and deeply disconcerting at once. At the same time, the work reflects on the role of photography as an agent of ‘truth’ in the criminal justice procedures. Perpetrators are often identified through photographs, but we all now know that photography is also prone to manipulation and can deceive. In these cases photography contributed to the transformation of innocent citizens into criminals, aiding law enforcement in obtaining eyewitness identifications and aiding prosecutors in securing convictions. In these portraits questions photography’s function as a credible eyewitness and arbiter of justice, while restoring a sense of dignity to those wrongfully accused. As Simon herself has said of the work, “Photography’s ability to blur truth and fiction is one of its most compelling qualities. But when misused as part of a prosecutor’s arsenal, this ambiguity can have severe, even lethal consequences. Photographs in the criminal justice system, and elsewhere, can turn fiction into fact. As I got to know the men and women that I photographed, I saw that photography’s ambiguity, beautiful in one context, can be devastating in another.”[13]

Taryn_Simon, The Innocents, 2002

1. Troy Webb. Scene of the crime, The Pines, Virginia Beach, Virginia

Served 7 years of a 47-year sentence for Rape, Kidnapping and Robbery

2. Larry Mayes. Scene of arrest, The Royal Inn, Gary, Indiana

Police found Mayes hiding beneath a mattress in this room

Served 18.5 years of an 80-year sentence for Rape, Robbery and Unlawful Deviate Conduct

3. Calvin Washington. C&E Motel, Room No. 24, Waco, Texas

Where an informant claimed to have heard Washington confess

Served 13 years of a Life sentence for Murder

4. Baseball field, Norman, Oklahoma

Williamson was drafted by the Oakland Athletics before being sentenced to Death

Served 11 years of a Death sentence for First Degree Murder

Victims who eventually become perpetrators is a subject addressed by Anila Rubiku in her series Defiants’ Portraits (2014). In Albania domestic aggression against women is considered a personal family matter, and violent husbands are hardly ever brought to court. In some cases desperate wives kill their violent husbands, and – as the courts generally do not acknowledge justifying circumstances – they are consequently sentenced to imprisonment. Anila Rubiku organised workshops with a group of such women in a prison in Tirana and used the art works they made to expose their predicament, the lack of protection for victims of domestic violence and vulnerable groups of women, as well as the absence of legal protection. Through these workshops, organised together with a psychologist, the women could express themselves in the form of art works and by narratives about their situation. Based on her experiences with the incarcerated women, Anila Rubiku created a series of artworks in drawings, sculpture and embroidery representing barred windows, each of which represents, in an abstract yet suggestive way, her insight into each of the women’s personalities, culled from the art works and narratives originating from the women themselves. For Rubiku these colourful barred windows represent a true portrait, more of an internal rather than an external likeness. The embroidered works are laboriously sewn by hand and Anila Rubiku sees the labour time she needed to make them as symbolic of the time that these women have spent behind bars. The barred windows, as well as the act of participating in a creative act by the women themselves, can be seen to express different kinds of hope and are a sign of possible freedom. Some of the bars are impenetrably close to each other, but others have been sawed through, or are bent apart, and thus offer an optimistic prospect of a liberated future. As a result of the project, many of the women Rubiku worked with were set free.

If incarcerated men are invisible, women are even more so. In 2011 photographer Dani Gherca visited Targsor prison, the only prison for women in Romania. The series Intime explores how a person manages to have some form of privacy given the fact that during the detention period inmates are forced to share the same space with other persons, every single day. Considering that the moment in the evening, when the lights go off in the detention rooms, is the only period of the day when prisoners can have some privacy, he asked seven women to write their thoughts on a piece of paper during those moments before fall asleep. The work features a portrait of the women, together with a handwritten note with their thoughts. Reading these notes provides a profound perspective on the privilege of freedom, but also the trauma of being split from family and loved ones, especially the prisoners’ children. Luis Camnitzer’s Last Words (2008) is also a text-based work that attempts to give voice to prisoners, in an albeit different manner. Camnitzer collected these final statements from the website of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, and used those that include the word “love.” Death row prisoners’ final statements are the texts that constitute Last Words. Forgiveness, apologies, declarations of love to families and spouses are combined with allusions to death and God. Printed on sheets of paper measuring 168 x 122 cm, the enlarged text come across as even more heartbreaking and disconcerting.

Luis Camnitzer, Last Words, 2008

1. 6 parts, Pigment prints, 167.64h x 111.76w cm

2. Part 1 of 6, Pigment print, 167.64h x 111.76w cm

David Brognon and Stephanie Rollin are two artists who also provide insight into the experience of prison life, from the inside. 8 m2 Loneliness (2013) is a motion sensor clock that plunges the viewer into a strange experience of suspended time, of an eternal moment: when the audience enters the room, the clock stops. It will not resume its course until the space is empty of all human presence. "When I return to my cell, it is my personal time that begins": these words from an inmate heard at Ecrouves prison marked the two artists. Time obviously continues tirelessly, but it is not the objective time that David Brognon and Stéphanie Rollin wish to refer to with 8 m2 Loneliness. It is the psychological perception that we have of time that interests the tandem of artists. The clock they came up with is marked with A130, which corresponds to a cell number. This clock with stopped time evokes the stretched to unbearable time felt by the inmate whose daily life is often marked by boredom and waiting, while the ‘eight square metres’ in the title of the work refers to the standard cell size.

David Brognon & Stéphanie Rollin, 8m2 Loneliness (A130), 2012-2013

Clock, presence sensor, 74 4/5 × 15 7/10 × 3 1/2 in 190 × 40 × 9 cm

Another, more historical approach to the subject was undertaken by Artangel, a UK commissioning body for site-specific artworks, which in 2016 organised a project called “Inside: Artists and Writers at Reading Prison.” Oscar Wilde served two years time in this prison, from 1895. He spent each day in solitary confinement, with nothing but the Bible to read for the whole of the first year and yet here, unbelievably, he wrote De Profundis, which took the form of a letter, because letters were permitted where books were not. At the time, it was believed that moral reform could be reached through the so-called “Separate System,” which in essence consisted of intense reflection and self-scrutiny, produced by such extreme isolation. In this system, prisoners were not allowed to converse, or even to see one another’s faces. Artangel invited artists and writers to pay tribute to Oscar Wilde’s prison years in a series of works that explore the agony of isolation. Artists included Vija Celmins, Rita Donagh, Peter Dreher, Marlene Dumas, Robert Gober, Nan Goldin, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Richard Hamilton, Roni Horn, Steve McQueen, Jean-Michel Pancin, Doris Salcedo, Wolfgang Tillmans, and Oscar Wilde. Many works already existed, but being exhibited inside the prison site – which was opened up for the first time – made them resonate in an entirely different way. Iconic works such Félix González-Torres’s Untitled, 1992/3, an unlimited edition poster which the audience can take away, with an image of a lone free bird lifting up into the sky, acquires another layer of significance contrasting confinement and freedom, captivity and flight. As part of the project, Wilde’s text was read aloud through the course of “Inside” by guest performers including Hollywood actors, the artist Ragnar Kjartansson and singer-songwriter Patti Smith. [14] “The prison style is absolutely and entirely wrong. I would give anything to be able to alter it when I go out,” Wilde wrote in De Profundis.[15] Upon release, he wrote two letters to The Daily Chronicle, attempting to draw public opinion toward reform, but to no avail.[16] Inside was a profound example of the redemption of history through art, but without falling into the trap of spectacularisation. The oppressive and sinister nature of the site remains all encompassing.

Other exhibitions consider criminal justice reform, such as the project Envisioning Justice at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2019, sketching an image of “what a world without prisons looks like.”[17] Some of the questions asked were: what are the harmful effects of incarceration, what would be a just legal system, what would a world without prisons look like and how can creativity be used to establish a fairer justice system?

Adela Goldbard’s project The Last Judgment (2019) in the Little Village community in Chicago is a participatory artwork that culminates in a pyrotechnic performance featuring the ritual destruction of large-scale sculptures. Accompanying texts are co-written and performed by Little Village residents. They deal with matters of incarceration and lateral violence, among other things. Jim Duignan works with incarcerated populations, creating a publication and installation to support and display visual art and literary content generated by artists and organizations that work with incarcerated individuals. Kirsten Leenaars project Present Tense (2019), is a video in which young men and women reflect on their lived experiences of the current justice system and prison-industrial complex, and perform individual freestyle raps about their own lived experiences. The video shoot itself was organized as a multi-day community event in which participants took part in the creation of the music video as authors and performers, providing the viewer with multiple points of connection, raising awareness about the lived effects of the current justice system and prison-industrial complex.

Nicole Marroquin works with the organisation Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative. Her project Loud Mud (2019), features audio recordings and ceramic amplifiers made by young artists participating in the initiative. These recordings are played through the amplifiers inside the exhibition and streamed on Lumpen Radio, a local station. Maria Gaspar, also mentioned earlier on, asked inmates to imagine what objects within the jail would say if they could speak. Animations were projected and sound works were broadcast through the city’s independent radio station. “We aimed to transgress the wall, to dissolve the concrete barrier that dehumanizes on both sides of its faces by transmitting stories from inside the jail through the wall and into airwaves of the city.” Sarah Ross contributed The Long Term (2019), a work that “reflects on the system that we currently have, that throws away people and, in the process, wrecks families and physically changes the makeup of our neighborhoods.” Through narratives of inmates serving life and long-term sentences, we hear stories about how prison shapes subjectivities and cancels out hope. Tonika Johnson creates artworks that can serve as tools for the endeavour of seeing the world from another perspective in order to get more people to accept that the right to recovery, rehabilitation and empathy is a fundamental human right. Her work Belonging: Power, Place and Impossibilities (2019) challenges us to acknowledge that prisons are in fact an extension of the US’s ugly history of racist policies and mass incarceration of black and brown people. Her photographs of young people of colour at locations of offenses expose how racial profiling, and skewed notions of class and crime contribute to attitudes, practices and policies that create and preserve systemic inequality, racism and social marginalization. A virtual extension of the exhibition features interviews with eight teenagers recounting their experiences and the ways in which they've been made to feel as outsiders.

Gabriel Villa’s mural painting We Are Witness (2019) centres on a confrontational image of a giant eye entangled in a vortex-like spiral, returning a confrontational gaze to the spectator. Villa’s work aims to stress the universality of injustice and point out that mass incarceration, racial profiling, police brutality are symptoms of a national sickness. He sees the root of this issue as a cycle, the circular madness of capitalism, which fuels the prison-industrial complex.[18]

Sometimes artists draw parallels between the jail experience and the voluntary confinement of the studio. Or they take inspiration from the physical structure of the prison, or from current research and activism. Here are six important examples, ranging from cell-like paintings to extreme durational performances. The following brief explanations are slightly edited from the original article in Artspace Magazine.[19] For Cage Piece the Taiwanese pioneer of extreme durational art, Tehching Hsieh, spent an entire year locked inside a hand-built wooden cage in his Tribeca studio. The sparsely furnished prison of pine dowels (equipped with a bed, a blanket, a sink, and a bucket) was sealed by Hsieh’s lawyer. A friend came once a day to deliver food and clean laundry and remove waste. Human contact was minimal, and even during the open-studio “visiting hours” that Hsieh held every three weeks, attendees could look but were disallowed to talk to the artist. Entertainment and other distractions were not part of the self-imposed plan, outlined on a manifesto: “I shall NOT converse, read, write, listen to the radio or watch television until I unseal myself on September 29, 1979.” Hsieh passed the time meditating, looking back on his life and career, and making hatch marks on the walls with his fingernails. Peter Halley, the founder of the “Neo-Geo” movement, transformed in "Cells" and "Prisons" typically Minimalist square and rectangular compositions into prison cells by adding vertical bars, inspired by Foucault’s Discipline and Punish, which proposed that confinement and surveillance were latent in geometric structures.

Countless artists have drawn comparisons between the white box of the gallery space and the prison cell, but few of them have made anything as eerily evocative as Robert Gober’s Prison Window (1992). Offering a glimpse of blue sky (actually an artificially illuminated painting) between hand-forged iron bars, it invites viewers to empathize with the incarcerated and, especially for those who know Gober’s oeuvre well, to think about more psychological kinds of confinement. Combining physical barriers and prison-like privations with the degradation of constant surveillance The House With the Ocean View (2002) counts as one of the most challenging in Marina Abramovic’s career. The artist confined herself to three elevated platforms in the gallery, which housed a bathroom, a sitting room, and a bedroom that could be traversed between but not escaped since they were connected to the floor only by ladders with butcher knives for rungs. She did not speak during the performance, and fasted for its duration. In his work New York State Unified Court System, (2016) Cameron Rowland takes on the issues of forced labor and racial imbalance in prison by presenting objects made by prisoners in New York State correctional institutions for compensation well below the minimum wage and sold through a nefarious-sounding state agency called Corcraft.[20] More recently, Hank Willis Thomas created a video projection for the US Department of Justice Building in Washington, featuring writings by incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people. The poems, stories and letters, which are projected in yellow and white text, aim to highlight the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on prisoners and were done in collaboration with the Incarceration Nations Network, a global network and think tank that supports and instigates innovative prison reform efforts around the world.

The Drawing Center in New York City organised in 2019 an exhibition called “The Pencil Is a Key: Drawings by Incarcerated Artists,” about “the nature of creative expression and what it means to be imprisoned.”[21] It “explores the many ways that artists have used drawing to envision their freedom during periods of incarceration.”(…) “The show reflects the art’s world’s increasing attention to the issue of mass incarceration.[22] Responding to systemic inequities in the United States criminal justice system, the philanthropist Agnes Gund created the Art for Justice Fund in 2017, which to date has committed $43 million in grants to activists and artists working on policy reform.”[23] MoMA PS1 in New York City organised in 2020 Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration, a major exhibition that runs well into 2021 and explores “the work of artists within US prisons and the centrality of incarceration to contemporary art and culture.”[24] It shows art made by prisoners and non-imprisoned artists who are “concerned with state repression, erasure, and imprisonment.” The exhibition shows more than 35 artists and pays attention to the COVID-19 crisis in US prisons, showing works made in response to it. Major themes in the exhibition are “the fundamentals of living - time, space, and physical matter - pushing the possibilities of these basic features of daily experience to create new aesthetic visions achieved through material and formal invention.” One of the artists in this show is Jesse Krimes, a Philadelphia based artist and curator, and co-founder of Right of Return USA, the first national fellowship dedicated to supporting formerly incarcerated artists, with a focus on criminal injustice and contemporary perceptions of criminality. While serving a six-year prison sentence, Krimes produced and smuggled out numerous bodies of work exploring how contemporary media shapes or reinforces societal mechanisms of power and control.[25] Another noteworthy exhibition on the subject was Aperture magazine’s Prison Nation, which included photographic portrayal of prisoners to complicate stereotypes about their perception. Coinciding with the photo magazine's spring 2018 issue, the exhibition highlights the unique role photography plays in creating a visual record of a national crisis, despite the increasing difficulty of gaining access inside prisons.[26]

However, there are issues to take into account when dealing with subject matter as sensitive as the criminal justice system; good intentions are not enough and one has to be aware of the politics of representation as well as the pitfalls of exploitation of vulnerable subjects. As Zachary Small argues in an article titled “What Curators Don’t Get About Prison Art” in The Nation of October 18, 2019[27] that “when it comes to showing the art of incarcerated people, fine-art institutions are buying into the prison-industrial complex.” (…) “Organizations hope that these public exhibitions can help raise awareness for incarcerated populations, but unscrupulous curatorial choices - publicising the artist’s work alongside their sentences, for one - quarter the incarcerated into harmful caricatures. What curators forget is the long history of commodifying prison art, which originates from the corrections facilities themselves: Art making, in many states, remains one of the few activities that those on death-row are allowed to do as they await execution.” But there are museums that stress the danger of exploitation of inmates. In 2017 the Hampshire College Art Gallery in Amherst Massachusetts organised an exhibition called “Made In America, Unfree Labor in the Age of Mass Incarceration.” It visualised the tensions between prisons exploiting incarcerated people for labour, and incarcerated people reclaiming their labour to create art and literature.[28]

Throughout the western world, especially in the US, exist many comparable locally or regionally operating initiatives, aspiring at the change and improvement of the living and working conditions of prisoners as well as safeguarding their human rights through art education programs and art exhibitions. In how far have visual artists shaped our image and idea of prison and prisoners and how has art influenced society? Prison is still a place where people are incarcerated for a certain amount of time, put away behind bars. But it is claimed that prisoners themselves have changed, as a consequence or direct result of different kinds of art programs carried out in penitentiary institutions. It is believed that art therapy can save lives, and research suggests[29] that incarcerated people have displayed positive behavioral changes[30] and reduced recidivism after participating in artistic-instruction or free-drawing sessions.[31] In general it is known that art can change opinions, instill values and translate experiences across space and time. Research has shown that art affects the fundamental sense of self.[32] But most importantly, it can challenge perceptions that are cemented and change the way we think about something. Art and visual language can educate, help illuminate, provide insight and empathy and generate affect for a group of people who remain society’s invisibles. Art’s contribution to the understanding of human rights issues has the added advantage of a different visual impact other than the one most often found in the media which is based on spectacularisation of “the pain of others” to borrow a phrase by Susan Sontag in her homonymous book, adding a nuance and complexity to these issues which is often missing in journalism and the daily public debate.

To conclude, the impact of art on issues of social justice and human rights became even more apparent following the death of George Floyd, an event that created a global public outcry. The death of George Floyd, who was arrested, but never made it to jail, because he was murdered on the spot by a police officer, engendered an explosion of art, all over the world, much of it in the public domain. Artists – professional as well as amateur – reacted in a variety of ways, in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement. In September last year, to cite just one example, the Smithsonian Magazine published an article entitled “How the Death of George Floyd Sparked a Street Art Movement.”[33] The article states that street artists are in a unique position to respond quickly and effectively in a moment of crisis. Similarly, artists working with issues of justice, human rights, and social equality have the potential to generate a political dialogue, indicating how art, activism and protest can create agency and actively contribute to demanding and sparking social change.

Katerina Gregos' curatorial practice focuses on the relationship between art, politics and society with a special focus on issues of democracy and human rights.

The author would like to thank Frank Lubbers for his invaluable feedback and insight in the writing of this text.

NOTES

[1]http://hummedia.manchester.ac.uk/institutes/cresc/sites/default/files/The%20Arts%20in%20Criminal%20Justice.pdf

[2] https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/Research-Art-Works-Oregon-rev.pdf

[3] Justice Policy Journal, Volume 11, Number 2, 2014 http://www.cjcj.org/uploads/cjcj/documents/brewster_prison_arts_final_formatted.pdf

[4] International Journal of Art & Design Education, June 2004, p.169 - 178 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/229631824_The_Rehabilitative_Role_of_Arts_Education_in_Prison_Accommodation_or_Enlightenment

[5] https://www.epea.org/wp-content/uploads/Research-Into-The-Impact-Of-Arts-In-European-Prisons-by-Dr-Alan-Clarke.pdf

[6] http://artsincriminaljustice.org.uk

[7] http://cpa-ct.org

[8] http://thejusticeartscoalition.org

[9] https://artbma.org/exhibitions/2019_slavery-the-prison-industrial-complex

[10] http://96acres.org

[11] https://www.chicagotribune.com/lifestyles/ct-envisioning-justice-illinois-humanities-tt-20190805-20190805-m3jtk2tgkfck5g43o4r5dnsxse-story.html

[12] https://www.reference.com/world-view/art-influence-society-466abce706f18fd0

[13] https://www.mocp.org/exhibitions/2000/5/taryn-simon-the-innocents.php

[14] https://www.frieze.com/article/doing-time-0

[15] http://www.gutenberg.org/files/921/921-h/921-h.htm

[16] https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/prisoner4099/historical-background/transcript-letter.htm

[17] https://envisioningjustice.org/exhibition/

[18] https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-6-artists-envision-prisons

[19] https://www.artspace.com/magazine/art_101/on_trend/6-artworks-about-prison-53588

[20] https://www.corcraft.org/webapp/wcs/stores/servlet/WhoWeAreView?langId=-1&storeId=10001&catalogId=10051

[21] https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/12/arts/design/the-pencil-is-a-key-review-drawing-center.html

[22] https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/20/arts/design/incarcerated-artists-drawing-center.html?

[23] https://artforjusticefund.org

[24] https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/5208

[25] https://www.jessekrimes.com/about

[26] https://aperture.org/exhibition/prison-nation-2018/

[27] https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/prison-art-shows-essay/

[28] https://www.hampshire.edu/news/2017/01/27/made-in-america-views-prison-labor-through-contemporary-art-lens

[29] https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED371139

[30] http://www.cjcj.org/uploads/cjcj/documents/brewster_prison_arts_final_formatted.pdf

[31] https://www.ncjrs.gov/App/Publications/abstract.aspx?ID=154810

[32] https://www.reference.com/world-view/art-influence-society-466abce706f18fd0

[33] https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/how-death-george-floyd-sparked-street-art-movement-180975711/

![Hang ’Em High (1968) [Κρεμάστε τους ψηλά] <br/>Αυστηρότητα και επιείκεια ως στοιχεία <br/>της θετικής γενικής πρόληψης](https://theartofcrime.gr/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/morozinis_cover_nov21-237x143.jpg)