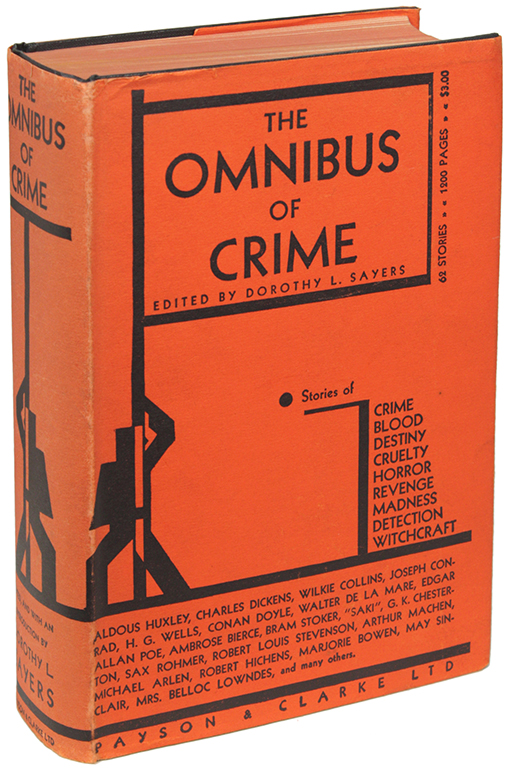

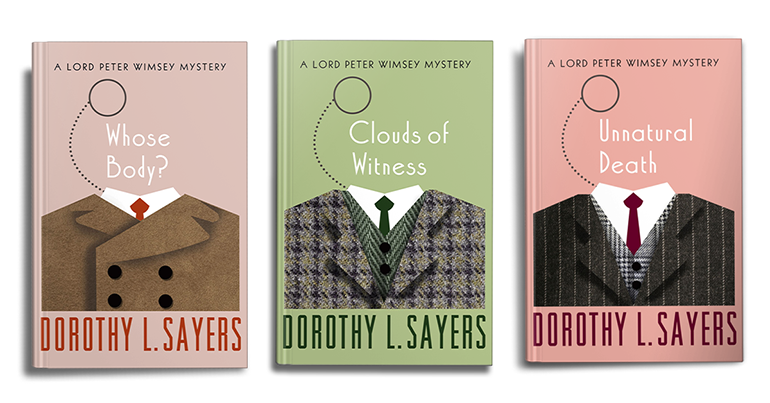

In her classic essay on the history of crime fiction Dorothy L. Sayers[1] draws a connection between the emergence and development of the genre in the English-speaking world, on the one hand, and the development of rational policing practices of detection and control, on the other. She further suggests that the popularity of the detective novel goes hand in hand with public sympathy in England veering “round to the side of law and order”. In a nonchalant, though hardly shocking considering the essay dates back to 1928, exercise in national stereotyping, she makes much of the ostensible fact that “it is notorious that an English crowd tends to side with a policeman in a row” whereas “in the Southern States of Europe the law is less loved and the detective story less frequent”.

But, unlike her creation, the wildly popular aristocrat-sleuth Lord Peter Wimsey whose deductive ability rarely betrayed him, Sayers infers the wrong conclusion.

Not that it is unwarranted to link the transformation of the criminal justice system with the emergence of detective fiction; quite the opposite. In its archetypal form, and by that I do not have in mind only the early works or the so-called Golden Age of the interwar period but also the genre’s later iterations such as the noir and the police procedural, crime fiction is typically pitched against or set within the criminal justice system.

Not that it is unwarranted to link the transformation of the criminal justice system with the emergence of detective fiction; quite the opposite. In its archetypal form, and by that I do not have in mind only the early works or the so-called Golden Age of the interwar period but also the genre’s later iterations such as the noir and the police procedural, crime fiction is typically pitched against or set within the criminal justice system.

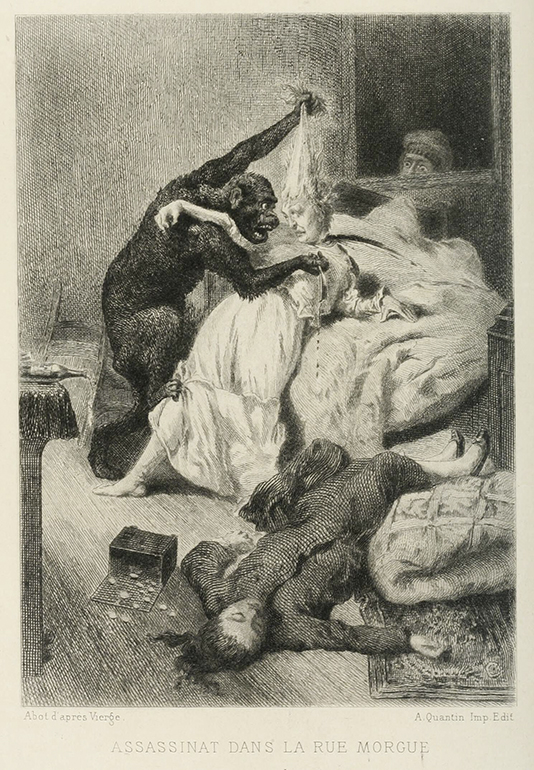

Edgar Allan Poe’s The Murders in the Rue Morgue, considered the first detective story and one that set much of the genre rulebook, appeared in 1841. It would have made little sense to readers that Auguste Dupin offers his brilliant assistance to the police prefect had the French Sûreté not been founded in 1812 and the London Metropolitan Police Force in 1829.

Sayers is also correct to point out that the requirement of material evidence as proof of guilt and the concomitant development of forensic practices and technologies paved the way for the fictional rational detective, who calmly and systematically examines the data, works out their logical connections and upshots, precludes the impossible and distils the truth. And it is the normative expectation that the wrongdoer will meet her/his comeuppance, because the administration of sanctions is centrally organised by state institutions, that sets the stake and adds dramatic effect. It would, after all, be disappointingly anticlimactic, should the detective go to all that intellectual effort, and often to considerable physical risk, if there weren’t any guarantees that the perpetrator would be punished.

So, if we focus on the transformations of the criminal justice system in the late 18th and, mainly, the 19th centuries in terms of practices and technologies, then it might seem plausible that crime fiction belongs in the same continuum. In this picture, the opposition is between criminals vs. law-abiding citizens, deviance and anarchy vs. law and order. The detectives, the innocent fringe characters of crime novels, but also the readers, who root for the sleuth, are all firmly placed on the virtuous side of that binary. So much so that, in his seminal essay on the typology of detective fiction, Todorov sets is as an explicit ‘rule’ of the genre that the reader must identify with the detective.[2]

All these players, real and fictional alike, each in their own way play a part in crime control. The characters and the plot emphasise and entrench established standards of conduct. The audience internalise those standards and they form expectations, which in turn pushes the market to reproduce plots and stereotypes thus setting the wheel in motion anew. It is no wonder that it has been argued, in a structuralist Marxist vein, that crime fiction is an ideological[3] or a repressive[4] state apparatus that completes the dominant order.

A new picture, however, emerges when we widen the lens to capture not only practices and technologies of crime detection and punishment but also the framework of rules and institutions of criminal law, in which the criminal justice system developed and largely still operates.

To do so, we have to deal in ideal types, as no strictly historical account, however extensive and accurate, would be able to yield the results that we are after. But ideal types need to be premised on an historical experience so I’ll stick to the paradigmatic case of England.[5]

Although most societies have for centuries been familiar with, and have practiced to varying degrees of cruelty, the idea that infringements of some established standards of conduct justify inflicting harm to the perpetrator in return, the criminal law as such only came into existence in modern times. In England the transformation started in the 18th and culminated in the 19th centuries. I will focus on two of its many facets.

First, over the course of a century, the criminal law expanded in a variety of ways. Crime transitioned from being a local issue of disorderly disturbance to a national matter. In the process, local juries were replaced by national institutions. This was mirrored in the gradual development of territorial jurisdiction, which defined the ambit of force and applicability of the criminal law.

The criminal law also grew in terms of volume. An increasing number of acts or courses of conduct were described as crimes. Some, assaults being a pivotal case, were removed altogether from the scope of private law and became a criminal, therefore public, and publicly prosecuted, matter. One pertinent upshot of this is that ‘crime’, rather than individual infractions and vices, became a separate category and a placeholder for a threat to the whole community as such.

Second, the age of formation of the criminal law shaped the concept and institutions of criminal responsibility, as we know it today.[6] The most crucial change was that blame began being ascribed not only for bringing about certain consequences with one’s actions but for causing that result with a certain mindset. Importantly, this suggests a new conception of the very subject of criminal law as an agent, whose intentional dispositions determine, at least to some extent, the meaning of her actions. Murder is murder, for example, because and to the extent that the person who commits it is a free individual capable of making decisions and acting on them and intended to bring about death.

This had various knock-on effects. For instance, the introduction of a subjective element complicated the process of ascertaining liability. It is one thing to prove that the accused did something that resulted in some harm and quite another that this was accompanied by the requisite psychological attitude. One institutional corollary of this was the introduction and gradual establishment of specialised defence counsel in trial, which suggests that, since the defendant is judged on the basis of her state of mind, then she should be granted the opportunity to account for it in the best way possible, so as to stand a chance of meeting the expectations and demands of the law. Represented by a legal expert, the defendant could approximate the idealised subject/object of the criminal law.

When crime fiction determinedly enters the literary scene to go on to become the ubiquitous genre that we know, most of these fundamental transformations are already in place. A great deal more happens, of course, in the twentieth century but the basic framework has already been set. It also provides the necessary background, against which crime fiction develops.

The first Arthur Conan Doyle Sherlock Holmes story, A Study in Scarlet, was published in 1887. In a nutshell – if you haven’t read it and are planning to, look away now – Jonathan Hope travels to Europe from America hunting down the two men who killed the father of his beloved and drove her to a premature death too from a broken heart. He finds them in London and kills them. He proves a worthy opponent but Holmes tracks him down. Suffering from an aortic aneurysm which he developed on his long and turbulent travels, Hope dies on remand before being taken to a magistrate, a happy man.

The Holmes tales, and this is true of all crime fiction, are primarily modern tales of law, not morality.

From very early on, Dr Watson introduces us to his new fellow lodger as clueless on matters of politics or philosophy but, at the same time, with a good practical knowledge of the law (on top of his proficiency in a range of sciences). In A Study in Scarlet Holmes assists, as he often does, the Scotland Yard officers Lestrade and Gregson, who might be hapless but their presence is a reminder of something significant, namely that the law of the land is the only yardstick of right or wrong that really matters in evaluating behaviour. It is clear that the police are bound by and serve the law, adhering to procedure. Seen from the reverse perspective, the police are only legitimated by the law and nothing beyond it.

Look at the reaction of Conan Doyle’s fictional Press to the crimes of Jonathan Hope: “If the case has had no other effect, it, at least, brings out in the most striking manner the efficiency of our detective police force, and will serve as a lesson to all foreigners that they will do wisely to settle their feuds at home, and not to carry them on to British soil.” In other words, that the two victims had committed crimes in America is not the concern of English authorities nor can it be relied on as a defence by Hope. The law’s reach is defined by the territory of applicability and, in turn, contributes to defining that territory. English laws apply where there is England and England is where English laws apply.

In 1928, S.S. Van Dine, real name Willard Huntington Wright and he himself a mystery writer, compiled the Twenty Rules for Writing Detective Stories,[7] drawing on the conventions of the Golden Age of crime fiction, which includes, among many notable authors, the great Agatha Christie and Dorothy L. Sayers. According to rules 18 and 19:

18. A crime in a detective story must never turn out to be an accident or a suicide. To end an odyssey of sleuthing with such an anti-climax is to hoodwink the trusting and kind-hearted reader.

19. The motives for all crimes in detective stories should be personal. International plottings and war politics belong in a different category of fiction--in secret-service tales, for instance. But a murder story must be kept gemütlich, so to speak. It must reflect the reader's everyday experiences, and give him a certain outlet for his own repressed desires and emotions.

The Golden Age detective novel reader does not crave random unfortunate events. She expects wrongs to be attributed to someone, someone to have willed them and this is a notable difference to the earlier period, in which the ‘perpetrators’ could on occasion even be animals as is the case in Rue Morgue.

This may be for a number of reasons. For example, being confronted with others’ innermost, dark intentions is frightening but, at the same time, it offers some relief that the psychological disposition of the perpetrator can provide a lead that can single out suspects and make the crime more easily detectable. The important point is that the form of criminal responsibility sets the framework of the plot. Sure enough, fiction takes it further to focus on ulterior intent (inheritance, revenge and the like), because that’s how it can tap into the pool of emotions and desires that drive wrongdoing, to which the reader can relate. Although motive has never been an element of criminal responsibility (the criminal law is generally only interested in the immediate psychological relation of the defendant to the act for the establishment of liability), its central narrative place nevertheless indicates that crime fiction is animated by the conception of the typical subject of the criminal law as an agent.

Note, finally, that the 19thc. institutional transformation of the criminal law does not only shape the standard content of the crime novel; it also has an effect on its reach. Had crime not become an autonomous category and had it not come to stand for a general threat that hangs over the community – a community which the concept of crime helps to define and ossify with the intervention of legal form – it seems plausible to think that crime fiction would not have been able to attract a readership from across the country, let alone across the world (although the international appeal of context-specific fiction is another matter that requires a separate analysis).

Yet, crime fiction deviates in a very important respect from the institutional structure that allowed for and framed its emergence and development.

A central aspect of the process of the modernisation of law in the 19thc. is its autonomisation. Law becomes a closed system and sets the terms of its own operation and reproduction. This holds equally for each field of law separately. The newly acquired systematicity of criminal law comes complete with a claim to exclusivity in criminalising, prosecuting, judging, and punishing in a way that is binding for everyone. In fact, if private law displays a little more flexibility and a relative openness to local or community-specific differences, say, through light-touch conflict-resolution procedures, criminal law is completely inelastic. Be it because of the high stakes for perpetrators and victims alike, be it because the monopoly of ostensibly justified violence is too valuable to share, everything alien that attempts to emulate the functions of criminal law and the institutions that it creates and regulates is either altogether prohibited or only bears some family resemblances to the criminal law (e.g. disciplinary rules). Accordingly, disapprobation for usurping the powers of criminal law takes various forms: criminal reproach for acts that would be legal had they been performed by an officer of the law; impermissibility of improperly acquired evidence; a ban on acts of revenge (with the intention to avenge a wrong having, at best, a partially excusatory force). Perhaps the pinnacle of this closure, and certainly its clearest manifestation in normative language, is the principle of legality, expressed in criminal law as the nullum crimen nulla poena sine lege (no crime, no sanction without law) principle.

One thing that all genres of crime fiction have in common is that they are played out in the margins of criminal law and criminal justice institutions. No one better personifies this than Christie’s Hercule Poirot: an outsider-insider; a Belgian refugee living in England; a policeman but retired; a detective but private; assisting the police but loath to share his methods and interim conclusions with them; an old-fashioned dandy in a world of changing mores and fashion.

The amateur sleuth is driven by the law – she or he almost always investigates crimes in the strict sense – but does not consider her/himself bound by legal rules, neither substantive nor procedural ones, that govern criminalisation (crime fiction shows barely any interest in distinctions, subtle or otherwise, between offences, even in the hands of the most skillful writer), the detection of crime (if anything, legislation such as the England and Wales Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 can be a bit of a wet blanket) or, often, its punishment (consider how often the perpetrator exercising her/his legal rights is designed to cause moral outrage in readers, as if their evil character disqualifies them from having rights). The sense of right and wrong that motivates the sleuth, and along with her/him the reader, is therefore extracted from the institutional order – very rarely do fictional detectives pursue a moral agenda that is completely alien to the actual legal order – but is also considered to have been imperfectly institutionalized, as if there is some objective normative order outside law that the legal order ought to reflect.

It is no coincidence that in that tradition, the police are more often than not portrayed as at least lacking in intellect and skills, if not as altogether incompetent. Crime fiction drives a wedge between law, as a set of community standards, and the institutions that are entrusted to enforce or apply them. This is what Holmes tellingly says to Watson in A Study in Scarlet referring to the officers of Scotland Yard: “If the man is caught, it will be on account of their exertions; if he escapes, it will be in spite of their exertions. It’s heads I win and tails you lose. Whatever they do, they will have followers. ‘Un sot trouve toujours un plus sot qui l’admire.’”

Professional sleuths straddle that same borderline space of legitimacy. When we reach the age of police procedurals, the all too frequently renegade cop navigates the same seeming paradox of breaking the law in order to uphold it. S/he assumes the role of authoritative interpreter of the law and its legitimate enforcer thereby appealing to a sense of law – not morality but law, that is an order that binds everyone irrespective of beliefs – which exists outside the actual legal system.

Crime fiction is determined by the criminal law of its time, both substantive and procedural, with respect both to its content and its narrative. Crimes must be crimes narrowly understood and they must be investigated in observance of the principle of legality. At the same time, crime fiction is also bound, again both in terms of substance and narrative form, by those conventions and expectations that govern social relations and literary practices. It depends on the institutional order for its existence and yet that institutional order is its most intolerable limitation.

The upshot of this is that, overdetermined in a way that no other genre is, crime fiction is at liberty to resolve normative conflicts arbitrarily. Thus, it becomes unruled and unruly, free to cross over the boundaries of its regulative orders at will.

To return to the beginning, Dorothy L. Sayers is correct to intuit that the typical English reader is on the side of some sense of rightness or propriety but wrong to think that s/he sides with the law. In detective fiction, criminal justice is rooted in a sense of civil order but not the one that the law actually shapes or one that exists at all. If anything, in its archetypal form, detective fiction is antithetical both to the idea of law as an autonomous and centrally organised normative order and as an actual, historically circumscribed system. Crime fiction doesn’t complete the legal order as a state apparatus that stabilises or enforces it; quite the opposite, it undermines it. It does not reflect the community of subjects of law (if anything, it often shows contempt for it), but imagines, and in doing so begins to bring into being, a new community, one that tries to reclaim the authority to define, investigate and punish crime. And perhaps that’s what readers, as Sayers imagines them, identify with: what they recognise as their own beliefs and not the “law”.

If we assume – and this is by no means an uncontested assumption to make – the project of modernity, especially in its manifestation in law, as inherently and necessarily progressive, because and to the extent that it reduces the complexity of the social world, then it follows that, by reverting to a pre-legal stage and misrepresenting controversial moral beliefs as generally binding, crime fiction is reactionary.

It doesn’t take much for audiences, which have grown exponentially especially thanks to televised crime drama, to mistake those images of the criminal justice system as reality and to act or form further beliefs on that misunderstanding.

But more pronounced than this sociological, and eventually political, risk is the danger of the misconstruction of the law being fed back into real world discourses, especially ones with prescriptive force.

A question in the 2008 USA case of Pennsylvania vs Dunlap was whether there was probable cause justifying arresting the defendant. Chief Justice Roberts dissented:

North Philly, May 4, 2001. Officer Sean Devlin, Narcotics Strike Force, was working the morning shift. Undercover surveillance. The neighborhood? Tough as a three dollar steak. Devlin knew. Five years on the beat, nine months with the Strike Force. He’d made fifteen, twenty drug busts in the neighborhood.

Devlin spotted him: a lone man on the corner. Another approached. Quick exchange of words. Cash handed over; small objects handed back. Each man then quickly on his own way. Devlin knew the guy wasn’t buying bus tokens. He radioed a description and Officer Stein picked up the buyer. Sure enough: three bags of crack in the guy’s pocket. Head downtown and book him. Just another day at the office.

* * *

That was not good enough for the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, which held in a divided decision that the police lacked probable cause to arrest the defendant. The Court concluded that a “single, isolated transaction” in a high-crime area was insufficient to justify the arrest, given that the officer did not actually see the drugs, there was no tip from an informant, and the defendant did not attempt to flee. [...] I disagree with that conclusion [...].

It might seem innocuous, entertainingly playful even, that Roberts employs the narrative tropes of the hard-boiled noir to make his argument. The effect of his language, however, if not his intention to start with, is to apply a veneer of correctness to his point through rhetorical manipulation. How can the experienced cop who “knew the guy wasn’t buying bus tokens” be wrong? And how can anyone, especially those sharp-dressed pansy lawyer types, question the judgement of someone risking life and limb in urban badlands to serve and protect law-abiding citizens? The noir reader knows whom to trust because the author has so constructed the universe of the book as to allow for no alternatives. That’s exactly what Roberts attempts in Dunlap making the most of the fact that the legal concept of probable cause is an open-ended one, ascribed its “regular meaning” – one of those so-called linkage institutions that allow for a certain degree of openness of the legal system to its environment. And should there be any residual doubts about the order of things, the staccato prose dispels them outright.

None of this is to say, however, that legal institutions are just without remainder because of their formal closure, which only provides some procedural guarantees, nor that crime fiction is a necessarily conservative genre. On the contrary, there is a way of reading it so as to gain a lot more than simply the enjoyment that one might take from, what I think is, a magnificent literary genre.

To do so we must resist every tacit or explicit invocation of an imaginary, unified moral community, governed by one, unquestionable conception of justice. Crime fiction will then emerge, first, as fully political. In fact, I would go so far as to consider it, from the cosiest drawing room tale to the most cynical procedural (which is of course fully aware of its nature), a par excellence political genre, because it deals with a crucial instance of our mutual relations as members of the community, namely how we harm one another, and with the most heavy-handed and consequential interference of the state with our lives, punishment. In other words, crime fiction is not a field of certainty but one of constant contestation. Second, we will appreciate its critical potential. Crime fiction can serve as a disruption, a subversive invitation to reconsider widespread conceptions of crime and state practices. And, since it so smoothly traverses across the institutional and the social, it can help us to reflect on how we do the same and how our different manifestations get tangled up and the impact this has on us and on others.

NOTES

* Manolis Melissaris graduated from Athens Law School and continued his studies at the University of Edinburgh. Until 2018 he was Associate Professor of Philosophy and Criminal Law at London School of Economics and Political Science.For the last few years he has been living in Cyprus.

[1] Dorothy L. Sayers, Introduction to the Omnibus of Crime (Dorothy L. Sayers ed.), Payson & Clarke, 1929.

[2]Tzvetan Todorov, ‘The Typology of Detective Fiction”’, in The Poetics of Prose. Translated by Richard Howard, Blackwell, 1977

[3] Ernst Mandel, Delightful Murder: A Social History of the Crime Story, Pluto Press 1984.

[4] Denis Porter, The Pursuit of Crime: Art and Ideology in Detective Fiction, Yale University Press 1981.

[5] I draw largely on Lindsay Farmer, Making the Modern Criminal Law: Civil Order and Criminalization, OUP 2016.

[6] See Nicola Lacey, Women, Crime and Character: From Moll Flanders to Tess of the D'Urbervilles, OUP 2008.

[7] First published in the September 1928 issue of The American Magazine.

![Hang ’Em High (1968) [Κρεμάστε τους ψηλά] <br/>Αυστηρότητα και επιείκεια ως στοιχεία <br/>της θετικής γενικής πρόληψης](https://theartofcrime.gr/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/morozinis_cover_nov21-237x143.jpg)