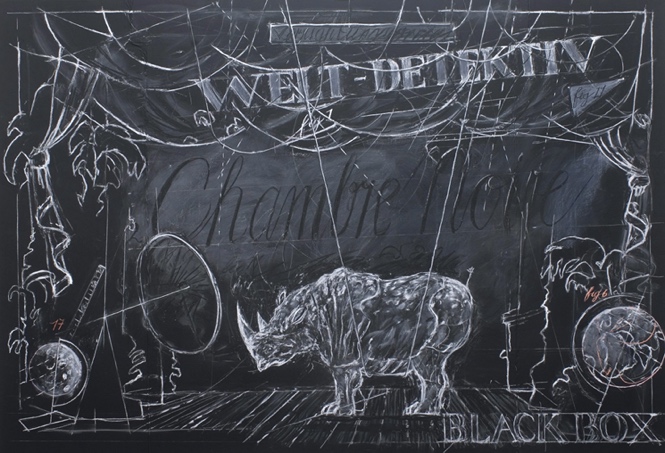

Drawing for Black Box / Chambre Noir (Rhino), 2005, pastel and chalk on black paper

Keeping an open-endedness, working with uncertainty right until the end.

W.K.

Α

s I begin my attempt to draw a rough sketch of William Kentridge before shifting to the particular focus of this article, I first need to declare my boundless admiration for the perfect identification of the creator and his work. And, more than that, for how Kentridge manages, despite being active in the margins of both the geographical and the art world, to always be at the centre of the global art scene, without ever losing touch with his past and his soul.

William Kentridge was born in 1955 in Johannesburg, South Africa, to parents who were lawyers and avid supporters of human rights and those marginalised by Apartheid. Kentridge is a renaissance-type artist: his multidisciplinary work combines drawing, collage, moving image, tapestry, printmaking, performance, murals, theatre, opera, set design, directing, constructions, sculptures. His personality matches the manifold nature of his work, as he studied history, political science and fine art, and tried his hand at acting, without much success, before deciding to dedicate himself to art. A brief biographical note on Kentridge would also mention that his works are, for the most part, scathing comments on inequality and brutality, the history and current socio-political conditions of his country, South Africa, the violence of the past and the impact of Apartheid in the present. That background, however, is no more than a starting point – his work is not limited to a particular geopolitical context. The art of William Kentridge is not political or militant, it does not believe in certainties and absolute truths, it does not promote moral excellence. It understands history as a collection of fragments, a fragmentary interpretation of the past. Through image, movement, sound, he investigates human nature, pain, sorrow, joy, the passion of life, and underlines the constant flow of the world, the ephemeral nature of things.

In that vein, Kentridge founded in 2016 in Johannesburg a centre for collaborative experimental arts, which he named “The Centre for the Less Good Idea”. Not simply because he is interested in what exists in the crevices of the grand ideas, but because his work itself is completed thanks to collaborators who make up his wider family, in the various stages of editing, creating the sets and the costumes, lighting, weaving, printing, casting…

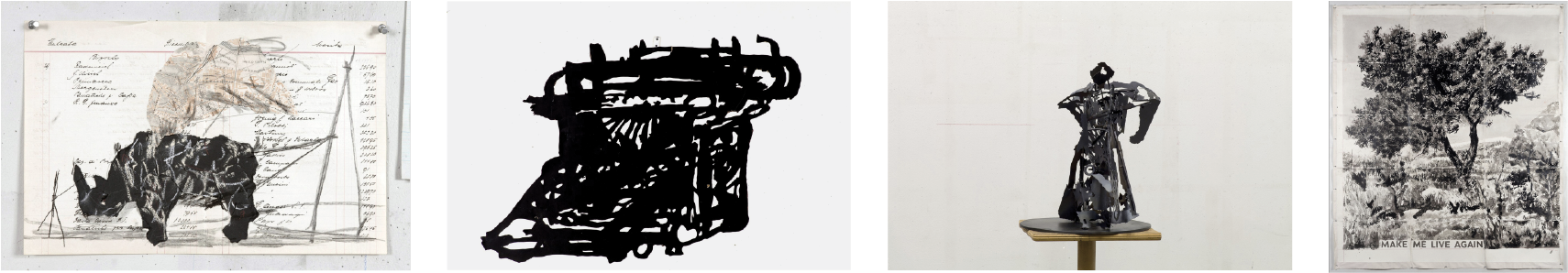

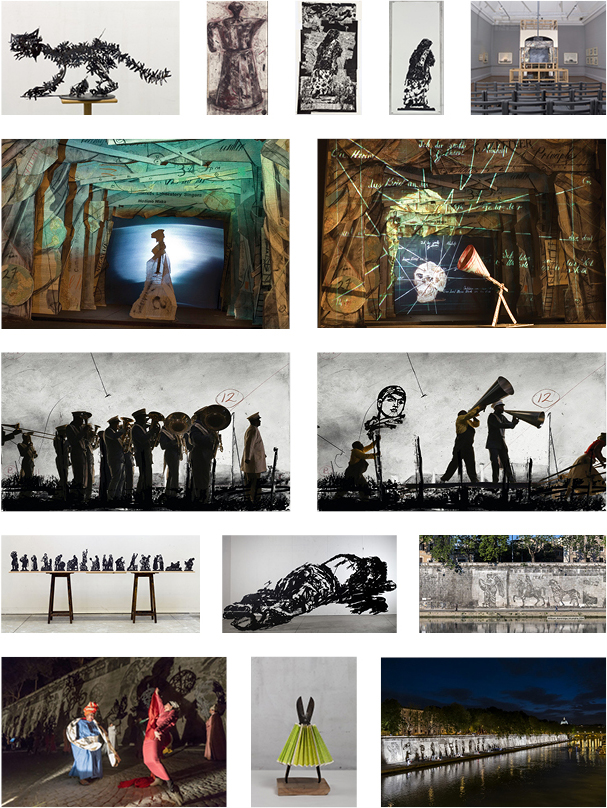

Refuse the Hour, 2011, chamber opera, fragmented lecture, kinetic sculpture and projection, 1 hour 20 min

Just like a theatre master who always wears the same costume – a white shirt and a dark pair of trousers – Kentridge seems to be directing the troupe of a personal comedia dell’arte, which, in most cases, he also takes part in himself as one of the main characters, like a big child who wants to live inside the world of his favourite toys. Featuring in prominent roles across the range of media that he uses to create his work, from drawings to animated films and the shows he stages, are the ostensibly incongruous figures of the megaphone, the rhinoceros, the typewriter, the coffee pot, the tripod, the cat, the tree, the human nose, as well as his own silhouette. Some of these figures are also a distillation of the fundamental issues that occupy him: the rhinoceros for the threat posed by hunters and the brutality of the colonialists in South Africa (and perhaps for the love of Fellini); the megaphone for the painting cone “that has found its place back into the world”, as he says, disseminating concepts and slogans in protest; the typewriter and the telephone for communication; the tree for the death that grows inside us and the loose leaf / “leaves” of paper and ideas; the nose for Gogol and the absurd that breaks down the expected; the coffee pot for its transformation into a cat and immediately after into the image of a self that changes while remaining the same. With the stroke of a brush and an unending line of alternating roles, everything in Kentridge’s work keeps transmuting before our eyes to become portraits of objects and figures, living between the light and the dark, in a personal shadow theatre.

Drawing for Black Box / Chambre Noir (Black Rhino), 2005, charcoal, chalk and collage on found paper Ι Small Silhouette 29 (Typewriter I), 2016, laser-cut stainless steel and acrylic based paint, 147 x 104 cm, edition of 4 Ι Cat / Coffee Pot I, 2019, painted steel, 42 x 100 x 22 cm Ι Make me Live Again, 2022, Indian ink on Phumani handmade paper, mounted on raw canva

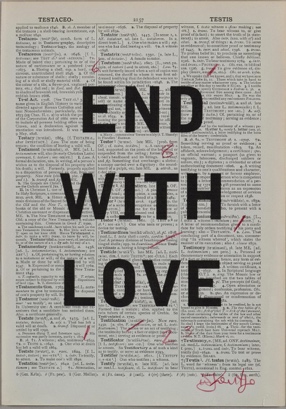

An integral part of Kentridge’s creative expression is the use of script in several of its different variations. Undertaking, in the first instance, the highly dangerous enterprise of writing among the figures he draws, Kentridge manages to create works of a dual nature, that move freely between the eye and the mind, between meaning and image, arousing the spirit and the body at the same time. Furthermore, he collects old cash books and second-hand dictionaries and encyclopaedias, to create a dialogue between his figures and ready-made script. Placing his forms over old manuscripts or the obsolete typography of valid information, he draws, as he puts it himself, “uncertainty on top of certainty”, declaring, at the same time, his love for the physical dimension of a book, its smell, its weight, its texture. Pages of books become the canvas of his paintings, and often the sets for his puppet theatre, his plays and his performances. Furthermore, script also appears in the form of short phrases that Kentridge has collected from his reading or has written himself. Painted usually in capital letters in black or a cobalt blue on the pages of books, these phrases, sometimes exquisitely poetic, function as much as autonomous visual sets of slogans/manifestos/prophesies of Dadaist origin, as organic components in the composition of a larger work.

Untitled (Irises in Jar), 2012, Indian ink on dictionary pages, 6 panels, 243 x 191 cm

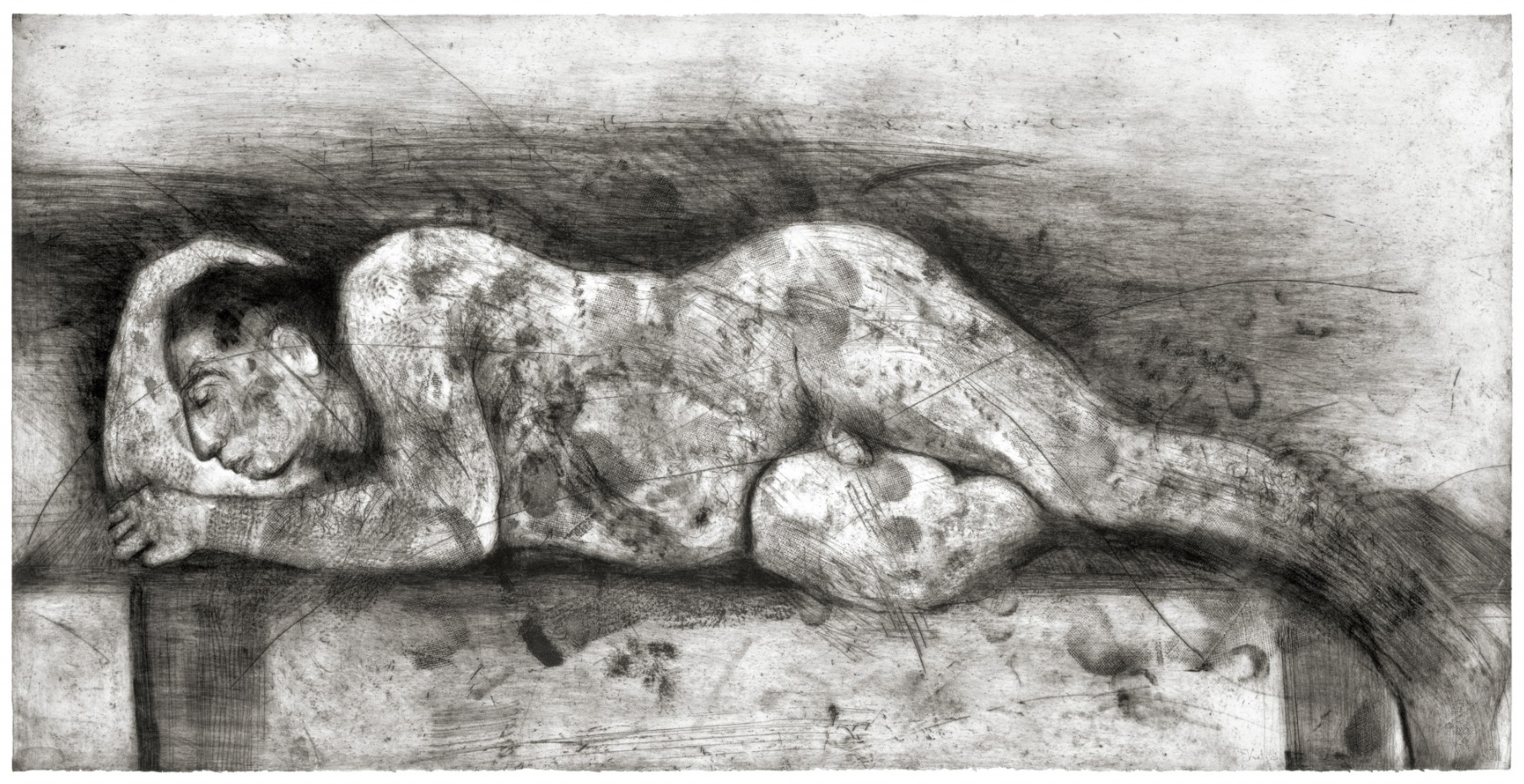

The world of Kentridge is articulated around the contradictions and the conflicts of a black and white monochrome, perhaps because the past of his country, South Africa, is enveloped by the darkness of the crimes of Apartheid; yet, the ultimate aim in his art is always the light. The white of his paper, on which he draws in black ink or charcoal, is the ground of his entire work. His figures are drawn on a sheet of paper before relocating, two- or three-dimensional, to his tapestries, his prints, his short films, his sculptures, the stage.

His drawings function both as autonomous creations and as the building blocks of his animated films: they become the associative images of dreams of a non-existent script, which develops from the changes that Kentridge imposes upon a single piece of paper, with numerous sketches, erasures, scribbles and marks upon the paper surface recorded by a camera. Their electronic sequence comprises the animation itself, while documenting and revealing various stages of the creation of a work and, at the same time, consecutive layers of memory on the paper. Even his large paintings are made on paper, on solid surfaces or assembled sheets, which are often removed and replaced by others, following different creative versions before the final work, which, in that sense, may never actually be final. Because Kentridge’s love for paper springs, without a doubt, from his faith in the non-definitive, the ephemeral, the fleeting and, as such, the precious temporary: the corrosion of time, natural flow, and the uncertainty of doubt as motives and vehicles for creation against the arrogance of certainty and the sterility of the static.

Even Kentridge’s famous pacing in his studio, in circles around his room and his mind, is yet another part of this fluid process, a creative procession that brings him into contact with the self: “Process shows you who you are … the process offers lessons of the self”. Kentridge uses his image integrally, often with irony, humour, and self-deprecation, at once a participant and an observer, as befits a work that bears the weight of its existence but not the pretentiousness of its self-awareness.

Nothing stays still or permanent in either life or art, as William Kentridge understands it. Which is why the processions, the parades, the movement of his figures are important features of his iconography – his subject matter seems to be transition itself – from his paper concertinas to his bronze sculptures, his projections and his performances: the figures that appear and move in profile, parallel to our field of vision, until they drift out of it, are the equivalent of the associative images of his drawings, which, negating and succeeding one another, make up his films, as well as the sets of his plays. The inherent uncertainty of the temporary is put forward by Kentridge as an unforced truth against imposed, absolute truths.

More Sweetly Play the Dance, 2015, 8 channel HD installation, four megaphones, 15 min, edition of 9 Ι Refugees (You Will Find No Other Seas), 2017, aquatint etching on handmade cotton paper, mounted on raw cotton cloth, bound with a sewn seam in the middle, 170 x 243 cm, edition of 14

Besides, imposition (direct or latent) as violence, and violence as crime, are fundamental starting points in William Kentridge’s subject matter: from the violence of being uprooted, the endless queuing and the deadly shipwrecks of present-day refugees, to racial discrimination and the confinement of humans to specific geographic areas, as imposed by the Whites of South Africa under Apartheid (1948-1991), as well as by the colonialists of the African continent before them. Against the monstrosities that were committed, Kentridge’s work points out the crime of violence universally and throughout the ages, without, however, accusing or preaching. His art protests, but with its own weapons – aesthetic emotion, which does not impose sentiment but, instead, allows it to come up organically, in the course of each work.

The years directly following the abolition of the laws of Apartheid (1989-1991) were a violent and chaotic period, as the Whites were vehemently trying to stay in power. The first democratic election in South Africa was finally held in 1994, won by the African National Congress (ANC) and headed by Nelson Mandela. In his film Felix in Exile (1994), made just before the elections, Kentridge’s alter ego, the white but sensitive Felix Teitelbaum, investigates the crimes and traumas of the violence in South Africa and the need to remember the people who lost their lives during the struggle for democracy.

Felix in Exile, 1994, 35 mm animated film, transferred to video and DVD, 8 min 43 sec Ι Ubu Tells the Truth, 1996-1997, animated 35 mm film, transferred to video and DVD, 8 min, edition of 4

Coming up raw and relentless through the contrast between the childlike, cartoonish style of the film and the violent episodes, surveillance, executions and tortures to which it refers, are the abuse of power, the annihilation of freedom and the encroachment of human dignity. Human skulls and bones, scissors and various torture instruments, along with an innocent bird, all tumble down together into a sort of drain/laundry for guilt, comprising one of the basic associative jumbles of images of the film and insinuating the violence of the crimes of Apartheid. The film traces the polarities of awareness and justice, violence and punishment, crime and forgiveness, while the title itself refers to yet another polarity, that contained in the name of the famed Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which was established in 1995 by Archbishop Desmond Tutu for the purpose of managing the trauma left behind by Apartheid. In order to investigate the atrocities that had been committed, the Commission travelled across the country and set up small public address podiums, providing the citizens with a platform to talk of their suffering or confess to their crimes in the hope of escaping punishment, so that the victims’ relatives could find out what had happened to their loved ones. These confessions also had another purpose, dual and indirect: to bring about repentance but also forgiveness, through the discovery of the truth. Nonetheless, these crimes remained gaping wounds in the history of South Africa, because, while certain criminals were forgiven through this process, many of the victims’ relatives could not give absolution to the impunity of the crimes revealed in those people’s courts, essentially stages for the narration of human tragedies.

One such stage, a strange sort of puppet theatre, is the setting for one of William Kentridge’s most important and most complex works, Black Box / Chambre Noir, which was first presented in 2005 at the Deutsche Guggenheim in Berlin. It was co-commissioned by Deutsche Bank and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, to investigate colonial crime and the first (German) genocide of the twentieth century. Between 1904 and 1907, by order of General Lothar von Trotha, over 100,000 people from the Herero and Nama tribes were murdered – that is, 80% of the residents of the then-German colony in southwestern Africa, present day Namibia.

Still from Black Box / Chambre Noir, 2005, animated 35 mm film transferred to video, projected back and front onto model theatre with drawings and mechanical puppets Ι Drawing for Black Box / Chambre Noir (Corpses in Tree), 2005, charcoal and coloured pencil on found paper

Those who were not killed were transported to concentration camps where very few survived, while skulls and bones of the dead were shipped to Berlin for scientific research aimed at demonstrating the superiority of the Aryan race. This mass crime inevitably brings to mind World War II and the Holocaust, raising the fundamental issue of historical guilt.

The work’s title (Black Box / Chambre Noir) functions as a trilateral reference. Its first side relates to the black box of a theatre stage and everything that takes place within it. The second pertains to the camera obscura, the dark room – forerunner of the photographic camera, whereby the light on a screen captures and conveys meaning to a unique image from the world outside. The third is connected to the impenetrable black box of an airplane, which records the conversations between pilot and co-pilot so that they can be consulted in the event of an accident.

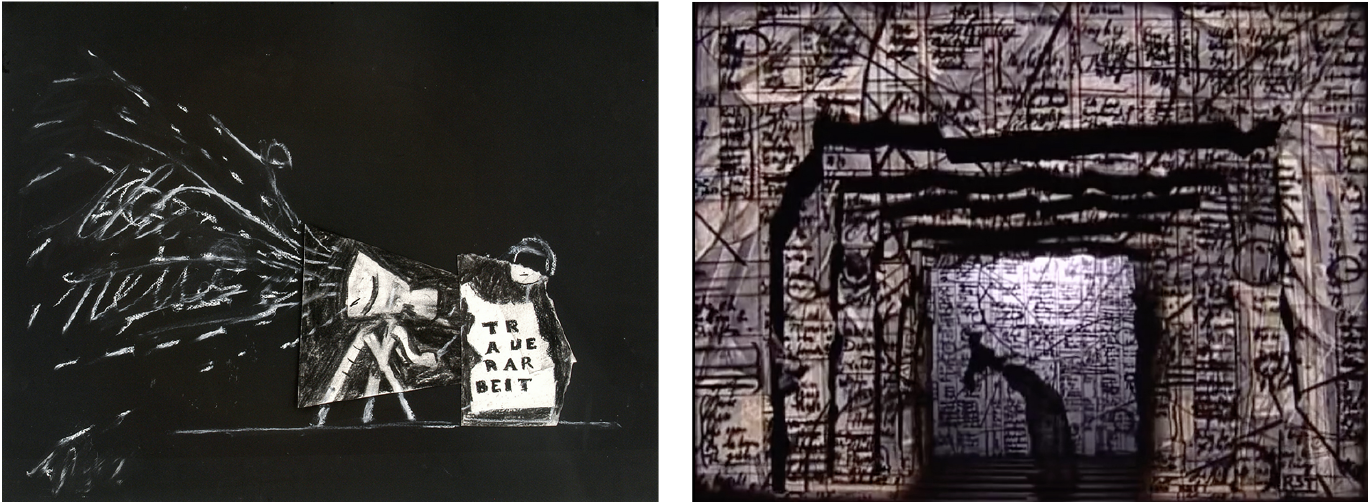

This ‘puppet theatre’ of Kentridge’s was created while the artist was preparing his Magic Flute opera. The fundamental ideas of the Enlightenment and, by extension, the allegory of Plato’s Cave run through not only Mozart’s opera but also, and inevitably, the Black Box. On a dark stage, the light gives meaning to the shadows and transforms them into figures; it is knowledge that leads to power. But if the Magic Flute refers to the positive side of the Enlightenment, the Black Box hints at its dark aspect: the potentially poisonous combination of certainty and violence. When the colonial forces decided to en-lighten the “Dark Continent”, they committed unthinkable crimes, leaving behind pain and death, a European burden that South Africa still bears upon its shoulders to this day – yet another reading of Kentridge’s processions –, the legacy of a destruction stored in the black box of history.

Still from Black Box / Chambre Noir, 2005, animated 35 mm film transferred to video, projected back and front onto model theatre with drawings and mechanical puppets Ι Drawing for Black Box / Chambre Noir (Figures with Sticks), 2005, charcoal, coloured pencil, torn paper and collage on paper Ι Still from Black Box / Chambre Noir, 2005, animated 35 mm film transferred to video, projected back and front onto model theatre with drawings and mechanical puppets

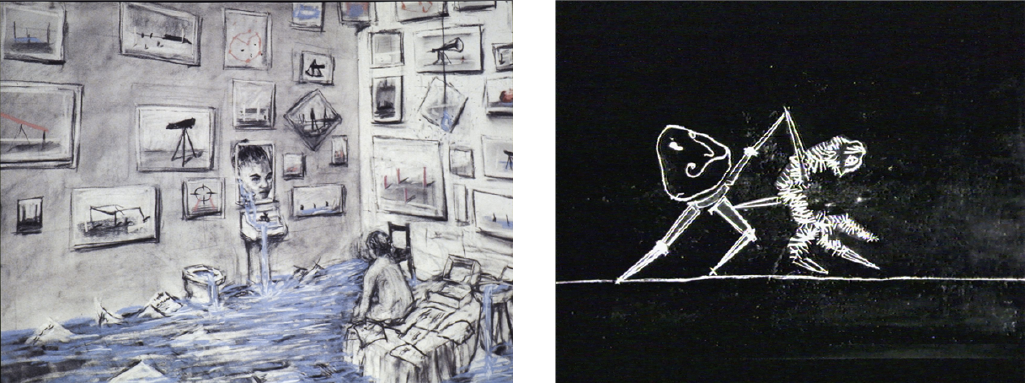

Kentridge’s Black Box narrates, once again, a story without a script, through his usual alternation of images that generate new images and ideas. The thread of a narrative unravels on a tiny stage with the help of a visible mechanism with pulleys and machines that move a fragile albeit baroque set of numerous screens. To the soundtrack of Kentridge’s close collaborator, the composer Philip Miller, and recordings from Namibia, a number of mechanical puppets and the projection, at the front and back of the stage, of a short film and images of dozens of works on paper (drawings in charcoal, pastel, collages, coloured pencils), come together to create a total, integrated work, which incorporates opera, painting, cinema, and theatre.

A man running, a woman of the Herero tribe wearing an ornate headdress (a reference to animal horns), a man/compass giving orders, a shattered skull, the megaphone man: everything performs a passing role, like consecutive acts in a theatrical revue. These three-dimensional ‘actors’ are in constant dialogue with the projected images, questioning the boundaries between the material and the immaterial, the real and the imaginary.

The megaphone man opens the show, and reappears at numerous points throughout, wearing a sign/placard with the German word “Trauerarbeit” (work of mourning). A short film projects images from the desolate Waterberg Plateau, where the mass slaughter began in 1904, followed, later, by another film showing the brutal killing of an unsuspecting rhinoceros, evoking the Herero genocide. Made with the poetry of the bare essentials, the tribal woman stands at the centre of the small stage, bending forward, and then leaning her body backwards, perhaps yielding to the pain inside and looking desperately for hope in the sky.

Drawing for Black Box / Chambre Noir (Trauerarbeit), 2005, charcoal, chalk and collage on paper, 50 x 64.5 cm Ι Still from Black Box / Chambre Noir, 2005, animated 35 mm film transferred to video, projected back and front onto model theatre with drawings and mechanical puppets

Against the fall of the crime of violence into oblivion, the crushing of every animal and human right, Kentridge starkly counterposes his images upon the stage of this children’s puppet theatre, speaking in a lοw voice about universal pain, loss of freedom, repression, memory, history. In this laconic mechanical invocation, this shattering curve of the small female body of a puppet, among screens of script enumerating deaths, hides the deepest tenderness, the artist’s greatest love for the victims of the Herero tragedy, for the victims of every act of violence

Kentridge’s art opposes crime with love, and that is why it never accuses. His work in its entirety is an open wound that he tries to heal over and over again, in the same way that he draws his images consecutively on the same sheet of paper. Both analogue and digital, at once contemporary and old-fashioned, his work lives in the new world, yet guided by old values.

Drawing for Second-Hand Reading, 2014, (detail), digital print on Shorter Oxford Dctionary pages, 27.2 x 38.5 cm

With small gestures and fragile materials, Kentridge has long denied grand ideas. He captures the composition of seeing, and decay, revealing the trails of memory on paper. He integrates time into his work, on the walls that he paints, knowing that they will be erased by the years or by people. Kentridge’s art does not seek to be eternal, nor precious, because it loves the poverty of poetry. It is art to carry life forward. And life to carry forward art.

(translated into English by Daphne Kapsali)

All images are taken from William Kentridge’s exceptional website www.kentridge.studio

Cat / Coffee Pot I, 2019, painted steel, 42 x 100 x 22 cm

Drawing for Studio Life, Episode 4 (Coffee Pot), 2020, charcoal, pigment, pastel and pencil on paper, 199 x 107 cm.

Widow of Lampedusa, 2017, woodcut printed from various woodblocks onto sheets of various sizes of paper, 207 x 117 cm, edition of 12

Drawing for Triumphs and Laments (Women Weeping for a Lampedusa Shipwreck II), 2016, Indian ink and torn paper on Hahnemühle paper, 107 x 46.5 cm

Black Box / Chambre Noir, 2005, installed at Johannesburg Art Gallery, September 2007

Still from Black Box / Chambre Noir, 2005, animated 35 mm film transferred to video, projected back and front onto model theatre with drawings and mechanical puppets

Still from Black Box / Chambre Noir, 2005, animated 35 mm film transferred to video, projected back and front onto model theatre with drawings and mechanical puppets

More Sweetly Play the Dance, 2015, 8 channel HD installation, four megaphones, 15 min, edition of 9

More Sweetly Play the Dance, 2015, 8 channel HD installation, four megaphones, 15 min, edition of 9

Il Processione di Riparazioniste, 2017, rusted steel, 15 sculptures, 27-56 x 119-43 x 2 cm, edition of 4

Pasolini, 2015-2019, steel, 304 x 703 x 10 cm

Part of Triumphs and Laments frieze, 2016, Piazza Tevere, Rome, May 2016

Triumhs and Laments, 2016, shadow procession with two marching bands, 32 min

Five Figures for Mayakosvsky (Figure IV), 2022, wood, felt, found object, found paper, coloured pencil, string and watercolour

Opening performance of Triumphs and Laments, Piazza Tevere, Rome, 21 April 2016

![Hang ’Em High (1968) [Κρεμάστε τους ψηλά] <br/>Αυστηρότητα και επιείκεια ως στοιχεία <br/>της θετικής γενικής πρόληψης](https://theartofcrime.gr/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/morozinis_cover_nov21-237x143.jpg)