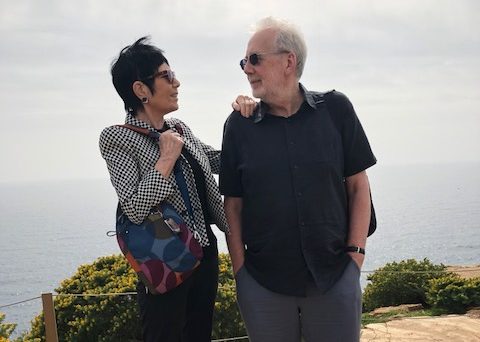

Papageorgiou: Dear Sandra, dear Antony this is your second academic visit to Greece (the first was approximately 10 years ago!) and needless to say how very deeply honored and delighted we all are by your presence. Last Thursday you gave a wonderful talk in our legal philosophy seminar on “Civic Punishment” and many graduate students and colleagues had the opportunity to discuss the paper with both of you. Today we will be doing something slightly different, we will be communicating as a quintet on issues raised by your theory but we will also ask you to comment on aspects of the Greek criminal law system from your own theoretical point of view. Before we start allow me first to phrase a question in the form of an introduction.

Over the last decades you have developed a communicative theory of punishment and criminalization that is arguably the most convincing articulation of a non consequentialist theory in the field criminal law. In fact it is a theory that seems to be steering clear of the metaphysical baggage some older and more recent retributive theories (notably Michael Moore) have not avoided. You understand punishment as an expression of disapprobation (disapproval) for a moral wrong that demands a special kind of apology on the part of the offender addressed towards its victim (and society). You use the expression secular penance. But punishment does not come as a reaction to any moral wrong per se but only to wrongs that are of some public importance and the claim on the part of the victim and society is carried by a special relationship we all have as citizens of the same polity. So the communicative theory of punishment seems to be doing something that deontological theories always aimed at which is to take the dignity of the offender seriously, to respect him as a person and to contain any attempt of turning him into an instrument of prevention. But this particular project has always been troubled by a certain paradox. What is the point of punishing if the sole purpose is retribution of a past wrong? Why make others suffer for wrongs that cannot be made good (and nothing will change in the future)? I think by connecting these claims with our civic duties in a sense you manage to solve this problem. Our civic duties have to be discharged in a sense and especially so when our behavior appears as a form of violation of those duties. And I also see a further bonus. Crime is seen as a special kind of immorality that concerns our common life and not individual behavior.

Duff: The first thing to say is that when I began writing on criminal law I saw punishment as being the central question. My first book was on punishment, and how one can justify it; but that was a mistake. The important thing is to start not with punishment, but with criminal law as a particular kind of institution, and start locating that within the structure of political community: what role should criminal law play in a political community of a particular kind—a polity that is roughly liberal, roughly democratic, roughly republican? What use would the citizens of such a polity have for something like criminal law. Now criminal law is a very particular kind of institution, and on our view the two essential features do not include punishment as such. We start with the substantive law, which defines crimes: these are wrongs that are recognized formally as public wrongs, wrongs that we collectively take an interest in; we censure them, we condemn them, and if you commit these wrongs you are called to account by your fellows. That's why the criminal trial is the second essential dimension of the criminal law. You are called to answer a charge of wrongdoing, and you are held to account if you are proved to have committed the wrong. The wrong is not any kind of moral wrong: it is a wrong that violates what we can call the polity’s civil order—the normative structure of its civic life. The civil order includes, of course, the institutions through which the polity governs itself, and a conception of its aims as political community; it also includes norms that define what counts as good and bad behavior within that community. Criminal law helps both to sustain that order and to constitute it. So the criminal law declares our central values—these are what we count as wrongs that concern us all as citizens; and then it provides for a certain way of dealing with these wrongs. Through this process we take seriously the wrong, and the offender and the victim as members of the polity. By calling the wrongdoer to account we recognize and mark the wrong, which is to do justice to the victim, and we treat the defendant as a responsible citizen by calling them to answer for what they've done. So the criminal trial is a kind of calling to account, which helps to define a certain kind of political structure within we see ourselves and each other as citizens who can answer for their conduct and who take the polity’s values seriously. Note that none of this yet mentions punishment. The value of criminal law lies in its formal definitions of public wrongs and the formal calling to account of those who commit them. That value is significant without yet talking of punishment at all.

So then we ask: if you've got this kind of institution in place—a system of norm defining laws and of calling to account—why would you add on punishment to that institution. What role would that play? That is the way we approach it. Punishment remains problematic, because we can imagine a criminal law without punishment: we can imagine a criminal process that ends with a formal conviction if the accused found guilty; he is then told “You have been proved guilty of this wrong; you should now recognize and apologize for it”.

So you have all that, including the formal verdict which declares the judgment. Why do you then add on punishment of a materially burdensome kind? And then I guess the question is: is it added on in order then to make the law effective as a deterrent, because if all we had was the trial people wouldn’t be deterred… is that the answer? Or is this the right question to ask?

Kioupis: I wanted just to ask you, you said also in the lecture on Thursday and you mentioned it also today, the relationship of the citizen in the civil community… you referred to the term “polity” and you say before coming to the second step to the question “Why punishment?”, we have already some substantive criminal law, if I understand it correctly. How would you define this situation, these terms of civil association, polity, what’s the relationship with the state? Is there substantive criminal law already in the polity? Before the state? Do we need the state to speak about criminal law before speaking of punishment? Or the state must come in a second phase just to guarantee the functioning of the system or the existence of the application of the punishment, or what? Could you say something about that?

Marshall: The quickest answer is to say that, on our way of characterizing it, the state is constituted by the institutions, it is the institutional form or manifestation of a political community, through which the political community realizes, or makes effective, its decisions. Law, of which criminal law is a part, is thus a political institution. It expresses the decisions of the political community regarding the way people should behave, the entitlements they have etc. So it is crucially important to make clear that when citizens answer to the criminal law they are answering not to the state but to their fellow citizens; and the way that this done is through the institutions of the state, which will be such things as courts and so on. The criminal law system, and the state’s function in legislating, are ways of making formal and public the underlying norms and requirements of the polity. The relationship is, however, always first between citizens. So, if you were thinking of the logical structure, then it would be that the polity, understood as that aspect of our public lives together which constitutes our lives as citizens, will come first. Such a characterization, I think, is one which then gives the particular form of the democratic state: you have to have the conception of a political community first and then the particular structures of the state as second in the logical order.

Kioupis: Yes, what would be the main characteristics of this polity? Is it spatial coexistence? Is it sharing some sort of common values? Speaking the same language? Having some sort of… being equal citizens in a way?

Duff: A polity can take so many different forms, but it normally includes spatial coexistence: because we are embodied beings, we normally live together physically.

Kioupis: Yes of course … Is it enough? Just living together?

Duff: No … If you just live side by side in a territory, that’s not enough. There must be some relationship in living together with certain forms of value that we share … some ambitions, some ends that we share. But then what form they take… there’s enormous variety.

Papageorgiou: Would you include in this model pre-modern society? Which has no sense of rights or no sense of democracy? Representative democracy?

Duff: Polities are not always democratic. Polity is a very abstract notion of living together as a community, which involves some relation of shared values: really it could be a theocratic community organized to live together under the word of God, in which citizens live to serve God (look at the Constitution of Iran)—the whole point is to live under God and serve his word. So we do not define polity as being essentially democratic or liberal; but if we ask what kind of polity we want, our answer will be a liberal democracy. For an analogy, think of a university: we live together, in part, as academics; we work together, we live in a certain form of life which is structured by what we declare to be our shared values—understanding, knowledge, education and so on. These shared values help to make us an academic community: but we also a sound structure of governance, which requires us to create institutions that are analogous to the state; and we need a code of ethics, which defines what counts as professional misconduct and how one should behave as an academic. But the code covers only a certain part of our lives: it governs, controls, my life as a teacher, not my private life; it governs that particular sphere of activity, academic life—it is a code of academic ethics. The code will define what counts as proper conduct as an academic, and also some mechanism for what is to be done about breaches: when someone commits an academic offence, what is to be done? There will be some process of calling to account for academic misconduct, and there will be some kind of penalty, some kind of sanction. A central point is that having a code of ethics in the first place is a way to taking our values seriously; but we must then also take breaches of those values seriously. Now an academic code is not a code for all our lives; it is a code for our lives as professional colleagues. Analogously, in the state and the polity, the criminal law concerns not every aspect of our lives, but only the life that we live together as citizens.

Marshall: I think that there’s a lurking question, alongside the question you asked just now. One way to put it, in the terms which have become reasonably common among philosophers at any rate, is how thick or how thin is our conception of the polity, how much has to be shared for there to be a polity at all. I think the answer to that is, in one sense, it can be quite thin. At the very minimum, you have to say that if anything is going to constitute a polity, to be a community at all, it has to have some shared conceptions, some shared values, which make sense of it, so that the members can speak intelligibly of a “we”. So now the question is how much “we” must share; how many values and which; how deep those values have to go? This is not something to which we have a particular answer. There are different forms of community constituted by different values. However, at the very limit, there has to be something of that kind, some set of shared norms and values, which are shared - not in the sense that everybody agrees absolutely with them - but that there is an intelligible possibility that they can at least have a disagreement about whether it is like this or like that. I think this relates then the question: “do they have to have a shared language?”. In one way you might say that is fundamental: because in sharing a language they share concepts and values. This is just the basic point drawn from Wittgenstein: without the language there is no community. Still, that is clearly a fairly thin notion. There remains this question for us: “how much diversity can there be?” Are there any concepts/values without which something simply could not count as a community at all? One might think, at this point, that this question is particularly important in the context of multicultural polities. So here we have a problem at the level of political theory. Do we need something like a domain of ‘public reason’ in terms of which the polity defines itself? Should we say that whatever different groups you might have, however multi-cultural the polity is, there must be some domain of discourse that they could all share in; a domain which constitutes the public domain itself? Such theories are, of course, not without their difficulties, but I don’t see how we can avoid, in the end, having some commitment to something of that sort for there to be a genuine polity. Of course people can exist in the same geographical area, living quite peacefully alongside one another and sharing nothing in the way of a general or global conception. Mere cohabitation though will not make them a community. So, I think there is here an important dimension that somehow needs to be more fully spelled out.

Tzannetaki: I think that more is required by your conception of polity, more things to be shared and other preconditions. I am thinking, for example, of Prof. Duff's account of communicative punishment and particularly of his notion of punishment as penance.

Duff: On punishment I think my views have changed somewhat in the past 40 years (thank goodness). I once took a much more moralized view: punishment should aspire to change a person's moral understanding, thus inducing repentance and self-reform; that was the central point of punishment. I now think that that’s misleading, because it treats punishment too much as an exercise in moral relationships, rather than in civic relationships. As I now see it, more clearly than I did then, we must distinguish between what punishment requires of the offender as a matter of civic duty, and what punishment might hope to bring about but doesn’t require. So it is a civic duty required of an offender to make this kind of apologetic reparation. The court says: Here’s what you must do … You must undertake … so many hours of community work or … pay a sum whatever… And that’s the way we hope you‘ll confront your wrongdoing and recognize it. The law requires that you undertake this formal ritual of apology, and we hope this will lead you to reconsider your life, to think about your offense, to repent, to reform and so on, as a matter of personal change: but all that is required is that you undertake this formal public ritual engagement, which then restores your formal standing with your fellows as a citizen. This ties in with forgiveness, which we discussed in the seminar on Thursday. As you pointed out, forgiveness is tricky. Take a crime which involves a personal victim: I defraud a friend or a colleague or relative: there’s a clear moral wrong that I have done, and also a criminal wrong of fraud. In terms of our moral relationship as friends or relatives, you might forgive and you might not. But what I owe the person I wronged, morally, is not just a ritual of apology: that’s not enough, among friends; it matters that I mean what I say. So as to our moral relationship, there must be essentially personal dimension: do I genuinely repent my wrong. A far as the law is concerned, however, what matters is not my relationship to my victim as a friend (that’s not the law’s business), but my relationship to her as a citizen—what I owe to her and my fellow citizens. And here aspects of the normative political perspective become relevant. In a liberal polity, we don’t inquire too closely into our fellows’ souls: what matters is our public engagement with each other, how we behave publicly. But behaving includes certain kinds of ritual behavior, such as rituals of apology and so on. The law requires that I undertake the appropriate ritual of punishment: that’s how I pay my civic debt to my fellows. They don’t ask, “Do you mean it?”: what matters is the ritual. I think that in my earlier work I did not emphasize that aspect enough, which took me too much into the realm of personal relationships. As I see it now, punishment comes in because something, a debt, is owed, beyond being convicted: I have incurred a moral debt, a civic debt to my fellows; and here’s how I can discharge that debt, by making this symbolic reparation, by undertaking punishment. Thus undertaking matters more than undergoing: I undertake the punishment in order thereby to apologize; but this is essentially a matter of ritual.

Papageorgiou: May I…? I have read very early on your papers and I think this turn over the years is very interesting and very constructive for your old theory … but still one acting in bad faith might raise the following question to you: all right, it’s not a moral education theory about punishment, it’s not about making the offender a morally better person, but is it perhaps a political education? A theory of punishment? By connecting the claim to punishment to discarded unheeded civic duty, can we say that the offender as a citizen is necessarily induced or inducted to a procedure that will see to his political reform? Couldn’t that be very problematic in a non-liberal, non-democratic environment? I mean, I was reading recently an incredible book, which you probably have read in the past, “Darkness at noon” by Arthur Koestler… There are incredible dialogues there… exactly about that … it’s in the context of a stalinist dictatorship … it’s about political re-education to a certain extent… it’s a politization of penance, actually…

Duff: Well, yes and no…

Papageorgiou: it’s a provocative… I don’t believe that you are exposed to that critique… but it’s just to provoke you…

Duff: The criminal law reflects a set of political values. And the law says to someone who is convicted of a crime: “Look here, you violated this important value, which is our value and should be your value”. And the punishment is certainly intended to reinforce that message: here’s what you must do to make reparation for your wrong, where the wrong is defined by the law. And certainly the hope is that in being punished you will also come to recommit yourself to those values. That’s the hope: but all that is required is that you now behave in the future in the way the law requires. Of course you’re right that what those values are will depend on the nature of the polity, and a polity which has illiberal values will then enforce those on its citizens; but what is crucial to any liberal system of punishment is that it gives the offender the moral space to resist the message. You tell me I have done wrong: I hear what you say, I undertake punishment, I do as required, I go through the ritual; but I retain my own beliefs, I’m not going to be coerced, and that’s an important aspect of liberal punishment—whereas if you’re a totalitarian, you’ll try to find some method which will bring about a change in the person's soul, and that’s what’s frightening.

Tzannetaki: What does the hard treatment element of punishment add to that message?

Duff: It’s a way of showing that and how this is a serious matter: you can’t just carry on normal life as if nothing has happened, because you did this thing. Think of a person who comes to recognize for herself that she’s done a serious civic wrong: I committed a fraud, and thought at the time “this is wonderful, I can get this money; but then I come to see it was wrong. I can’t just say, “oh well, that was wrong, I won’t do it again”, and then carry on: to take it seriously involves some way of responding to what I have done, and it’s a feature of our human social lives that we find material ways of representing what’s serious. So I undertake some burden to make clear that I mean my apology: I do something for you. Analogously, we typically find material ways of expressing gratitude: If you’ve done me a great service, and I am grateful, I don’t just say “thank you very much”; I give you a present, or take you to dinner—I do something material to show that it’s important. So too with the wrong: if I am to show you that I recognize my wrong, this will take some material form; that’s how we show each other that we are serious.

Tzannetaki: So, the material form punishment takes has an important symbolic function.

Kioupis: You are speaking of a ritual as a reaction to the public wrong committed by the offender it’s a form of recognition by the offender of his wrongdoing … this has to take a certain form, so that it’s serious recognition, it is something that matters and has usually material forms […] Very interesting. I have read an article of yours regarding the relationship between restorative justice and retribution… For me it was a very important article in the sense that it dismisses the current view that these two concepts are opposite to each other. You show that there is a relationship between them I would like to ask: If we understand punishment as a way of formal ritual recognition of the offenders' wrongdoing, how do we define this retribution and this restoration process? You say crime is public wrong, it's not just a relationship between you and me, it relates to the whole of the community, so this public, formal recognition has to take a public form through the trial. And that means that the restoration of the damage done cannot just be a material thing happening between the offender and the victim. What would you see as a necessary additional element, as the retributive element of the punishment? Does it depend on the type of the offense? On the gravity of the offense? It is always there? Can we still speak of Punishment when there is just a material reparation or is it just civil law thing? Perhaps these are too many questions…

Duff: If all I do is repair the particular harm I caused— I restore your property, or repair whatever damage I did — that does not seem to address the wrong. If I just caused that harm inadvertently or innocently, I still should try to make it good: but to address the wrong I need to do more than merely repair the harm, though of course the repair itself can have a spiritual quality of apology. We’re dealing here with conventional meanings, what we take to be a proper expression of an apology. The Community Service Order is a very nice example of this: if I’ve been convicted of vandalism, and my sentence is to go and spend some hours repairing other damaged property, that’s a very appropriate kind of punishment; I show my awareness of the wrong I did, and thus also repay it. This provides an appropriate relationship between punishment and crime. So we have conventional methods of representing the wrong and the apology for it. I agree that to a degree, while it is not quite arbitrary, it is a matter of social convention as to what the sentence, what I am undertaking in this way, actually means; so there is no a priori answer to the question of which modes of punishment are appropriate. Of course we also hope to evolve towards more humane modes of punishment: we abandon flogging, we abandon torture and corporal punishment, because they they’re very expressive, they express a terrible message—one of humiliation, in the case of physical punishment, or dismissal in the case of capital punishment. Punishments must be ways in which citizens can address each other, so we can rule out some kinds of punishment as being inconsistent with civic recognition. Still we can think of three kinds of punishment. First, the paradigm of community service, where I do some work for the community to make up for the damage I caused. Second, the paradigm of probation, where I recognize that I did wrong, which raised a question about my civic standing: so I should be monitored for a certain period, I should meet my probation officer, maybe I am in some kind of program; I recognize that I need to reform my civic life. Third, imprisonment, which is problematic: roughly the thought is, given what I’ve done, this terrible wrong, I cannot live with you as if nothing happened, not even by doing some community work; we can’t live together in that way, at least for the time being; I need to have some period of seclusion, to mark the rift my crime caused between me and my fellows. I think we can make sense of imprisonment in those terms, —we could think of it as marking a recognition of a temporary rift. So in the end, by way of probation or community work or imprisonment, in the end this restores our relationship, by undertaking the punishment as retribution: but again that’s a very formal restoration, not personal but civic; and that’s important.

Kioupis: I think that’s very interesting, because normally among criminal lawyers, criminologists there’s a loose talk of restoration, in a sense, in a very simplistic way, just repairing the material damage done… which is of course not the core of the criminal case, could I just add another question… about what I also found very interesting on Thursday was that shift from the traditional view that we do something to the offender, by punishing him, while you stress that the offender by participating in a polity, accepting, apologizing, participating in this formal ritual, has an active role to play… would you like to elaborate a little bit on this … because I think it’s a very original idea… and it goes against the intuitions of many people … or the traditional thinking of criminal law. Would you like to comment a little bit on this?

Duff: This takes us back to our starting point. We start out with the question of what role criminal law, understood as substantive law and the criminal trial, can play in a polity. And so we must start with the polity itself: what kind of polity do you want to live in? A polity whose citizens can see it as theirs: In a true democracy is it our polity, it is our law. We have then an active role to play in making the law, in sustaining it, and in applying it. What is interesting is that often in legal theory, including criminal law theory… the law is seen as the creature of officials. The law is made by officials, administered by officials, and we as citizens are required to obey it or disobey it; we’re just passive. But that’s not a democratic polity. That’s why the notion of a common law is very important: a common law is our law, reflecting our shared values, and we have an active role to play in that law. If you start with that thought as being important, and the thought that offenders don’t cease to be citizens by breaking the law, then as citizens who do wrong they are still citizens, they still have duties to play their part in the civic enterprise; that is to say, it’s important to recognize an offender still as a fellow. They still have an active role to play, they are still engaged as active participants in the enterprise of the criminal law, and by committing their offence, they incur new duties, of a civic kind—a duty, I think, ideally to redress their crime if they’re guilty, and a duty to make reparations to their fellows.

Marshall: We should here go back to your first question about the relation between retributivism and restorative justice. I think that one thing the restorative justice idea and the restorative justice procedures emphasize, and which is useful in understanding the position that Antony is characterizing, is that restorative justice requires something not just of the offender, but of the victims and the rest of the community. This one of the really important things I think about the restorative justice movement. Similarly, on Antony’s view, the offender has to take an active part in their own punishment as it were, but that this person is restored to the community requires that the community recognizes that, and behaves and reacts accordingly. This then makes the whole idea of someone’s having the civic status of being an ‘ex-offender’ (as seems to be the case in. our jurisdictions) really puzzling – as if being an ex–offender is a civic role you go on having in perpetuity after completing your punishment. For a genuine restoration to civic status that would make no sense at all.

Tzannetaki: I think, Prof. Marshall that this could take us to the question of the general conditions on which the legitimacy of communicative punishment depends. These, Prof. Duff, you analyze wonderfully in your contribution to the book “Punishment and Political Theory”. Could you elaborate a bit on the condition of the “moral standing” of the state as well as on the importance of “the accent”, “the voice”, as you phrase it, of penal communication?

Duff: Yes—if you see the criminal process as one of calling a supposed wrongdoer to account, we need to ask who is calling, and by what right we call the person to answer to us. We need to look at our relationship with him until now: is he really treated as a citizen—does he get, and has he received, the recognition that citizens deserve from each other? If not, then our standing to call him to account is undermined; that’s a very important part of the picture But also that feeds through into punishment: if you are to punish a person as a citizen, then it matters both how he is punished, and also how he is then received back after the punishment. There’s a wonderful article by Shadd Maruna talking about having a ritual of re-entry. As things are now in Britain, in England, you serve your prison term, then you are released at the end of it perhaps not quite in an underhand way, but in a very quiet way: when you leave the prison, if you’re lucky you are met by a friend or family, if you are unlucky you are on your own; you almost sneak back into society, and you face the various kinds of disadvantage which attend being an ex-prisoner—it’s hard to get work or to get a home, So you are not welcome back: you sneak back as it were. Imagine instead this ritual of re-entry: you are welcomed back from prison publicly by your fellows, and that makes clear the point that if we take punishment seriously as this kind of civic debt, the debtor has paid the debt, and the creditor must receive the debt, and mark the debt as being paid; you have paid your debt and now all is well. And that is what’s missing very often.

Tzannetaki: Clearly one of the strengths (as well as challenges)of your communicative account of punishment is that it seeks to make punishment justifiable to those on whom it is being imposed; that it takes the punished person's point of view and the legitimacy of punishment from her perspective seriously into account. This refers, of course, to a great extent to the question of how one is punished, with regard to both, the mode and the amount (i.e. severity) of punishment. You discuss extensively and convincingly the issue of the mode of punishment but its appropriate severity remains, I think, an open question. And this is an important question given also the excessive prison sentences of some countries, USA par excellence. You do say, of course, that punishment should be used sparingly and only as a last resort. Your general liberal- communitarian political theory tends to greatly limit, if not almost preclude, harsh punishments. One would, moreover, assume that excessive sentences should be avoided so as not to undermine, as von Hirsch puts it, the moral message and the preconditions of the communicative function of punishment. Could however, in your view, the right amount of punishment- and I am referring here primarily to the overall, the net severity of the prescribed punishments- be defined more tightly? Given your communitarian approach would you perhaps say that it is the feelings and the standards of the community that should serve as the yardstick for deciding the right amount of punishment?

Duff: There are two questions: One question is, of substance, how do we fix the right amount of punishment? And then there is the procedural question: who decides the right amount of punishment? Do we involve the community through some kind of political process; or is it done by professional judges? So these are two different issues. On the first, I think, there is no a priori answer; we are here very much in the realm of convention: what is enough to make the message clear, to count the reparation; and there is no fixed answer to that. One hopes that…

Tzannetaki: On what does it depend? It is contingent, right?

Duff: Yes. What do we see as being enough to take that crime seriously? And we hope that … one way to go about that is to follow von Hirsch and adopt a decremental strategy: we start at where we are, and ask: could we reduce the punishment?

Tzannetaki: According to von Hirsch's proposal in “Doing Justice” the ideal towards which a decremental strategy should aim would be three years confinement for serious crime, with the exception of homicide for which five years would be the normal limit. Only homicides of the most heinous nature could receive longer sentences than that.

Duff: Yes and at some point we say: “That’s not enough; that can’t be enough to mark the seriousness of the crime”. What that point is we have to find out gradually—find out how far we can go before we must say that isn’t enough. I’m not sure there’s any other way than that to do it. We need to be clear ourselves about what punishment does to the person—what it is to be imprisoned, for instance. That’s important, but it’s often missing in public reactions. Given that, can we believe that that amount of punishment is enough to do justice to the crime, to mark the crime? And again I can’t think of any plain objective answer to that: it’s not written in the sky somewhere that this fits that. We say… here’s what we collectively can accept as enough.

Tzannetaki: But then we will tend to stick to the existing conventions whilst the idea behind the decremental strategy is that we try to gradually change these conventions.

Duff: We must start where we are: we can’t say “Here is the ideal pattern, let’s try to move towards that”; that is not available.

Papageorgiou: There is no platonic theory of punishment…

Duff: Punishment is harsh and painful: so let’s try to reduce it, that’s the decremental strategy. So we start from where we are, and see how far we can moderate—see how far we can reduce how many offences are met by imprisonment for a start, or how long prison terms are.

Tzannetaki: So parsimony would be a criterion. But with regard to what aims?

Duff: You don’t punish more than you have to, to serve the aim of the punishment. If the aim is deterrence, then that’s the question. If the aim is an adequate expression of recognition of the crime—that’s still parsimony in relation to that aim. This leads to the second question about procedure: how to go about deciding this? And this comes back to questions in political theory. On one view of democracy, this should be a collective enterprise: we collectively decide, either in relation to particular crimes or in general, through public debate about what we think is appropriate; and that prospect scares many people.

Tzannetaki: It is indeed scary, very much so.

Duff: And one answer is that we need to rely on experts: they will tell us what to do. I am very torn on this, because I can see the attraction of a genuinely participatory democratic process, which will include determining levels and modes of punishment: if we are serious about being a democratic polity, then this must be part of our political deliberation. But yet as we are now, we find it dangerous to go straight down that route. We need to work towards a position in which we could have that kind of public participation … except that … sorry, one more thing. One important distinction between criminal law and some modes of restorative justice is that criminal law is formal, controlled, organized. In restorative justice you have a meeting with the offender and all those who are involved, and everything comes in, with no formal constraint on what can happen, what can be said, what can be dealt with; and that’s one of the ways in which it’s frightening—everything might come out. But a criminal trial is focused on just this particular thing, on this particular charge: did you do this? It’s limited, constrained. So too with punishment: it is constrained; we’re dealing with a particular defined civic wrong. That’s why it matters that the law formally protects people against the unconstrained encroachments of some kinds of restorative justice, and that’s why sentencing must be in that way formal too: sentencing must do justice to offenders, and so the courts need that kind of formal control. That is why we can’t go straight to the community to determine the punishment: a better answer might be to say that we should try a decremental strateg and see how far we can push it.

Marshall: It does seem to me that the “how much is enough” question always looks as if it’s a quantitative question. But the more you press on the argument the more it seems not quantitative so much as qualitative. It always seems to come down to this question: “what is it we take seriously and how seriously do we take it?” But there will be disagreement, sometimes very deep disagreement, in any polity about which things are more serious than others; about what is the most serious kind of wrong that you can do. There is going to be argument about it, and it is something that has to be discussed. Indeed, one might say it should be discussed more, and with more seriousness, that it often is, both by citizens and in the legislature. A good example of this is something like drugs crime: if you have any kind of criminal law with respect to drugs, the question is “why do we think drug taking is so wrong, why does this seem serious to us?”. People will disagree about it and what we take seriously is a question of political morality. Then we must ask what counts as taking it seriously. Again I don’t think that the way we should look at it is as a quantitative matter, how much of this is imposed, but what it is that is imposed.

Duff: Sometimes it comes to that. Popular culture matters so much. I was struck by the Breivik case in Norway. He killed 70 people, but there’s an impressive side to the response: there was shock and horror, but also a very sober kind of public reaction. He went on trial and the trial was a serious enterprise, and he was heard, and so on; and he was sentenced to 20 years, which is the maximum that you get in Norway; and in prison he had 3 cells—a bedroom and a study, and an exercise room. Now there’s a serious discussion in Norway about whether 20 years was really enough, or whether they should extend it somehow: there’s a very serious, sober discussion about whether there should still be this maximum sentence for any crime at all, or whether some crimes need more. But imagine that in England or in America, someone got 20 years for that kind of crime: the popular press would go mad, especially if he had three cells to himself and a television: there would be hysteria at the thought that a person could get so light a punishment for such a terrible crime; the popular culture, the political culture is so different.

Tzannetaki: You will allow me to insist on what I see as an important question even though we have already repeatedly touched upon. As a communitarian do you think that we should or that we shouldn't evaluate these different conventions differently? I mean there are academics like Ian Loader, amongst others, who take a clear stance in favor of penal parsimony and penal moderation and try to further these. Is this compatible with a communitarian political philosophy or would the latter rather dictate a heightened sensitivity vis a vis what people in each country and each community presently regard as the appropriate level of punishment?

Duff: It’s difficult because although I want to be able to say “That’s how people should feel”, that implies some external standard. I’m sure that we should be moved by the thought that imprisonment of any kind is harsh, burdensome, and problematic morally; even if it is in three cells, it’s still problematic. So we should see that—the loss of liberty—as itself a serious punishment; and we should, if we have any humanity ask ourselves (and this is where we get back to parsimony, of the kind that I want): how much do we have to do in order to take the crime seriously? I can’t myself see that the answer is that we have to imprison them for 60, 70, 80, 90 years. If I try to think about Breivik, it’s tricky, because it’s unclear what we are to make of his standing as an agent. I’m torn two ways. On the one hand, what would it be to recognize that you have committed this kind of terrible crime, as the crime that it is: how could you live in that recognition, how could you live recognizing that you have murdered 80 people; could you get back to normal life at all? I think it’s revealing to put the matter in this first personal way. First you have to repent, but you might think “I can never get back into normal society, I must live a life of seclusion”. But on the other hand, if you look at it from the second or third person perspective—what do we say to the person who committed the wrong—surely there must be a way there; or are we to say that some crimes are such that there’s no way back from them, no way back into the community? Or should we say that for any crime, however serious, there must be a way back—in which case there must be a limit to their punishment?

Kioupis: You mentioned the example of Norway: maximum imprisonment 20 years … in England or the United States, in Greece we have nominal punishments: someone is sentenced to 3 times life imprisonment but is released after 16 or 20 years… So there is the problem of a nominally very high sentence, which practically doesn’t mean anything more than 16 or 20 years. Scandinavians are more sincere than we are. They don't like to play this symbolic game like we do … Apart from certain exceptional cases in Greece there are hideous murderers or rapists who are … convicted to life sentences or 40 years and are out of prison after 15 or 20 years … I 'd like to come back to a very important distinction you made between the qualitative and the quantitative element … nowadays we criticize quite rightly our criminal system… but we have another phenomenon… for a crime you may be sentenced to imprisonment of five or six years, which is very harsh punishment but at the same time you may be sanctioned outside of criminal punishment socially, politically, professionally to almost something resembling physical destruction, you may be destroyed in one day, thrown away from your job, put away from the whole of society… at the end you might get a very light punishment. It's not a matter of quantity always, 5 years in prison, the social extinction in one day which comes more, but I’d like to use in this example of qualitative element to discuss you project of “trial on trial”. Sometimes we say the structure of the trial, what role does it play in the criminal system one problem in Greece is the following: sometimes this harsh treatment does not so much take the form of punishment in the form of a sentence imposed by the court, but the punishment is the procedure itself. You get to be accused, deprived of rights, you have perhaps no access to bank accounts, you stay in prison though you are not convicted, criminal procedure lasts for years and years, you have to pay a lot in costs and you have all the negative publicity through the media and the society, and perhaps at the end you are either not guilty, you are an innocent person at the end, or you get some sort of punishment, which is of no importance to you in comparison to what you have suffered. Would you like to say something about your project, about this normative picture of the trial? Because I just read some parts of it and I find it very interesting you stress this shift from the traditional mode of trial, sometimes now you get plea bargaining, some sort of trial through documents. Anything you would like to say on this topic?

Duff: There are three major points in what you were saying. One is the further effects of conviction: you are convicted, you receive a sentence; but you also find that you have a criminal record, and you find that you face further formal and informal consequences. Formally, in America sometimes you find that you can’t get public housing, you can’t get education and so on; and there are also informal social consequences: these are the effects of conviction—that’s one set of issues. Another point concerns the pre-trial procedures, which include detention in prison awaiting trial, and the kinds of constraint. In fact I happened to check on the Greek prison population this morning: it seems that Greece imprisons fewer people than we do…

But of all those who are in prison, almost 30% are there awaiting trial or on remand, not sentenced: that’s quite a high proportion. That’s very problematic. I think what happens in fact is, (I’m again talking about England, Britain and the United States) once you are formally charged with an offense formally then often you are assumed to be guilty: so while awaiting trial you can be locked up because you are assumed to be dangerous. In England the conditions for being given bail, being released pending your trial used to depend on whether you were likely to abscond and escape your trial, whether you were likely to interfere with witnesses, and—as it was often put, were you likely to commit further offences while on bail: but this assumes that you are guilty, and the presumption of innocence seems to have vanished. But that’s deeply problematic—to treat people awaiting trial as if they were guilty: we need to think far more carefully about these aspects of pre-trial procedure. The third thing is, if the trial is process of calling people to formal account we must enable them to take part in that process: they must get the support they need , including the support of a lawyer, to play their role in the process. If we have duties, we have a right to be enabled to discharge our duties. If I have a duty to answer, I must be able, and enabled, to answer: this means that I must not be subject to assumptions of guilt, I must get the support I need, and the process itself must be such that I can take part in it. These are all ways in which our current procedures fail dismally to do justice to offenders.

Marshall: I think one of the things you mentioned, which seems to undermine the just trial, has to do with increased publicity, which is particularly noticeable in our jurisdictions and yours as well. By which I mean, for example, the ease with which the mere fact that someone is charged with an offense becomes widely known, even before any public procedures are engaged. Now of course it has to be right that these are public matters, the process has to be open and not private, not secret, but the nature of the publicity which we now see puts huge pressure on the presumption of innocence for example. This is something which is very contentious in Britain and now discussed more openly and publicly by lawyers and others. They now do raise a concern about the ways in which the presumption of innocence, which we might always have assumed to be a fundamental principle, is being seriously undermined. And I think this is one of the areas which some of our conceptions of the just trial (in the Trial on Trial book) do bring into focus. We, the citizens, have to have a proper understanding of these fundamental commitments of our own polity and its values. What something like the presumption of innocence means and how fundamental it is, is something that needs to be part of public education. What public discussion there is shows that people, including many politicians and public commentators, are really not clear about what it must mean and about whether there ought to be any such principle. I think this is really important to realize about public discussion. There is a lot of pressure on the courts that can give rise to the erosion of important procedural protections. So, now there is increasing demand for anonymity, for victims or accused persons particularly in rape cases. And this is very hotly contested, so there are here really important questions about what a just trial is, some of which we discussed in the Trial on Trial book. In the light of the discussion we are having now, much of what actually happens in trials is completely unjust; in Britain, certainly, the accused person in the court can sometimes appear to have taken no part at all in the proceedings. They sit in the dock and are talked about by lawyers, but have no idea themselves about what is going on. They do not understand the proceedings, and appear to be seriously detached. Indeed, sometimes you wonder why they need to be there, why they are sitting there at all, because everybody is talking around them. Now that is a deficiency which can be easily addressed, it’s not something that is so difficult to counter, and it should be remedied if we are to make any sense of the idea of being called to answer to your fellow citizens for what you have done.

Tzannetaki: But again all this varies from culture to culture. The Scandinavians, for example, and their media, are apparently much more constrained in how they portray crimes and criminals.

Marshall: I think this is an important feature of the argument in the discussion we had immediately prior to this. It’s not that Scandinavian countries happen to have such a different system from us. Our systems, the values that underpin them, are not at all different from theirs. It is rather that our system has become distorted: we have a lot of pressures on our system which come from a lack of funding, a lack of resources and so on, which are making the system ineffective.

Tzannetaki: Very interesting data actually exists on the influence of different socio- economic, cultural and institutional contingencies on the severity/ leniency continuum of the penal system of various countries, as indicated at least by their imprisonment rates. Large scale statistical correlations between such contingencies and prison rates have highlighted the importance of factors such as economic inequality, welfare provision, people's trust in institutions, a consensual political culture and so on. And there is also very solid theoretical work on, for example, the institutional requirements of Penal moderation, the influence of political- economic structures or of the differing characteristics of what Garland terms "the Penal State".

Papageorgiou: These factors go with more severity …

Marshall: I was thinking not so much about the level of punishment, but the institutional structures and the way the trial systems work. I think that the deficiencies in this, in some trials as we currently have them in the UK, a lot of trials are failing in exactly the ways we were talking about. Take the way people are held on remand for long periods of time for example: I don’t think that is because we are committed to a different set of values, or interpret values differently. We can talk to people in these other jurisdictions about shared conceptions of the presumption of innocence and ask how it works and whether it fails there also. We can learn then from these other jurisdictions because we share conceptions with them.

Duff: We’re told that in Norway they do genuinely see offenders as citizens who have offended [S. Marshall: “that could be true!”], whereas in England and America we see that defendants are already being seen as guilty; that’s partly why we don’t have adequate funding to give them support they need. So there are differences at least in how we actually understand and live the values. This also goes with the point that a more effective welfare state itself reflects an inclusivist ambition—it shows that we are serious about these values; whereas an ineffective welfare state shows that we are not serious about this kind of inclusiveness. So there may be deep differences in how we connect to the values we profess.

Tzannetaki: It is worth mentioning here the political will of countries which decided to drastically lower their prison rates-Finland being the prime example, which more than halved its prison rates over a period of decades, starting from the early '60's, in a process of reorienting its Penal policy to the values of the group of Nordic and Scandinavian countries to which its people felt they belonged.

Marshall: In relation to the earlier discussion, I think the question then about what ought to be the level of punishment, how that should be decided in any community, depends on who you are and what question you are asking. It seems to me in the United States for example, the question about whether they have prison rates that are too high, whether their sentences are too long and too harsh, is an internal question which they can and do ask themselves. I don’t think there is some platonic answer to it, and you can see this is a genuine question for them and wonder what makes sense for them and of course you can in that way discuss it. You can imagine a community in which they have what look to us like very high levels of punishment, but where there would be no potential for anyone to ask the question because it would not make any sense. About that then we would just have to say this is how they do things.

But then within the US they do have discussions, and we can ask whether it make sense to raise the question about whether life without parole is disproportionate. And this does seem a rather weak way describing it. So it is possible to argue intelligibly that this is just something which is totally unacceptable, not just that it is ‘too much’. What I mean by saying that is that this is an internal questions—that you can find resources within the US constitution, within the values that they take to make up their own polity, that provide the grounds for answering it. Of course, they may persist with the practice even if it is by their own standards unjust, and then the question of why they persist becomes a sociological one.

Tzannetaki: one last question…

Papageorgiou: Last? I have at least ten!

Tzannetaki: What are, in your view, the necessary conditions (political, cultural or even religious) for your notion of communicative punishment to be applicable and work according to its spirit? I am thinking, for example, that cultural variables, such as the level of people's directness in their communication, their readiness to undertake responsibility for their actions and face the consequences of these, or even the relative importance of the element of pride in how we want to portray ourselves to others might all be relevant and yet very different between the people of a northern protestant country, a southern catholic or orthodox country or a middle east muslim one. Could we thus say that it is the variation of one factor, e.g. cultural, which can influence in very different ways the applicability and "effectiveness" of communicative punishment?

Duff: So if you start from the inside, and ask what attitudes are needed for punishment to be, to become, that kind of exercise in respectful communication: well, you need first of all to be able to see the person to be punished as a fellow citizen—that’s what you need to achieve, but that inclusive kind of respect is not seen very often. Again this is difficult, as we saw on Thursday: can we have an entirely unconditional respect for others as fellow citizen, whatever they do; or whether in the end a person might do such terrible things that we can’t take that view. But putting that question aside for the moment, the vast majority of offenders and offences are such that we can still see the offenders as genuine fellow citizens; so we must ask: can we do this to a fellow? I once heard it said that a prison officer should ask: could you accept your son or your brother being in this kind of prison? If you couldn’t, that shows there’s something wrong with it. We should ask something similar. These are our fellow citizens: so can we do this to them, while still seeing them as our fellows? If that is a serious attitude, punishment might become what it needs to become. But the question then is: what needs to be in place before that, if we are to have this view of each other as genuine fellows. What kinds of political structure make that possible, or harder; what kinds of cultural structures make it possible? And there I get lost: I don’t that kind of expertise.

Tzannetaki: These are probably the same factors that lead to less severe punishment. And probably also to an easier endorsement of the idea of restorative justice.

Duff: Yes, Certainly it would go with certain kinds of welfare. If we owe each other equal concern and respect, concern has to do with support welfare, and education. So it’s no coincidence that countries with well established, well accepted, welfare systems also tend to more moderate punishments, because within such welfare systems we see that we have this kind of connection to each other and this kind of debt: that seems to me entirely plausible. This ties in with work that Nicola Lacey and David Soskice are doing on different kinds of capitalism and how they connect to penal policies …

Marshall: … They are looking into political economy in relation to structures of punishment.

Duff: The more unconstrained free market capitalism you have, the more you tend towards penal severity; and that seems entirely plausible, if you think about the set of attitudes and values that go with capitalism, how you see each other, as compared to more controlled welfarist systems …

Papageorgiou: Especially, totalitarian capitalist systems … There seems to be more than one types of offenders that would not easily come under this expectation of having an active offender. So nicely told on Thursday. An offender that would not even care to be included in some kind of open humanist, humane kind of moral dialog with the citizenry, with the polity, with the citizens and their victims. White collar criminals I am prepared to pay whatever it is to be paid in money or in prison term and get rid of it as fast as possible, but I do not want to get into any kind of dialog about my … and penance… concerning my relations. You also have political offenders who acted… I mean terrorists … who are extremely… we have in Greece cases like that, most cases of convicted terrorists are like that, who clearly say I don’t repent I don’t recognize the state… you also have another third kind of offender I recall here the case of somebody who was writing beautiful lyrics for popular music… Akis Panou, who actually killed his son-in-law because he mistreated his daughter. And this guy, who actually died in jail, never repented his crime … he followed his code of honor so to speak… that was it; he served his term but he never repented his crime and never tried even to get some kind of understanding … So you have these three different situations. What do you do with them? How should a democratic society, a democratic polity deal with these people? Especially the most difficult case, the political …. those who are accused of crimes committed by some kind of, because of some kind of radical ideology.

Duff: In that case there is a question about how far we remain within criminal law as opposed to the laws of war. If they define themselves as enemies of the state, then that’s what they are: they’re engaged in a war, and we have a different normative structure within which they can be understood and addressed. In a way then they might be an easier case, since we don’t have to deal with them within the framework of criminal law.

Papageorgiou: They don’t have constitutional rights then! This is another thing…

Duff: Until they are convicted, they are presumed innocent: so they have all their rights. But if they are convicted of this kind of crime, if they avow that they don’t recognize the state and are waging war against it then we are within the laws of war—where you have of course rights of various kind. This is one way to approach the terrorist case. As for the other two cases, remember the three ways of seeing your punishment that we discussed on Thursday: as a burden that you can’t avoid, as a matter of dutiful obedience, or as an active that you should undertake as a citizen. We should aspire to a system in which we can say that civically you should see your punishment in the third way, as an active citizen. But we should not demand that attitude as a matter of legal duty. If a person said “OK, I just want to make this as painless as possible, to get rid of it and get back to my ordinary life”, we should be disappointed civically, but they’ve not failed to do what the law requires of them. That’s one reason why fines are often not a good mode of punishment, because it’s too easy to pay the fine and say “That’s it”. Again, we require that they undertake the punishment, but we don’t require that they mean, it or that they in fact repent. As for the father who killed his son-in-law, you might also compare fathers who kill their daughters because they marry the wrong person: they still believe that they were justified, and we should not try to coerce them into abandoning their beliefs. We try to make it very clear that what they did was certainly wrong, a profound moral wrong, and say that here’s what they must undertake as punishment for it: but in the end they must be left the space, the room, to retain their own beliefs. All we can demand is that they act as the law requires.

Kioupis: May I interrupt… I d' like move to another sort of questions… to help our readers to get to know you as persons. For example, your experiences as professors, as scholars, your thoughts about the relationship between theory and praxis etc.

Duff: We both taught philosophy for almost 40 years in a small department of philosophy in Scotland, and after that, we spent five years going part-time to America to a law school there, teaching a very different kind of student: this was a very different experience. In general, I suppose our ambition is always to get our students to think, to engage. The theory and praxis question is quite hard in Scotland, in England, in Britain. For it is hard to get that connection going directly between philosophers and the political world, because governors tend to mistrust what they call “intellectuals”. Perhaps the most we could contribute as philosophers is by teaching our students, who will then go out into the world themselves and will become lawyers, business people, politicians and so on: they will then take with them a certain kind of critical attitude towards what they are doing—they will think about it critically, take a critical perspective. If we can induce them to do that, that’s a large part of the point of teaching political, moral, legal philosophy: to get students to understand what the issues are here, and so help them to form their own lives as they go on. Some of us engage more actively, we talk to commissions, or committees, about matters of political and legal ethics and so on. But that tends to be for most of us less effective, because you are just one small voice among many that they hear, and often not talking in terms that they want to hear. We have more chance of making a difference to our students, or sometimes through writings that are read by particular people, and they then go on and think further…

Kioupis: Was there a significant difference comparing the experience in Scotland with USA, the American university?

Duff: It was very different. In Scotland we were teaching mainly undergraduate students of philosophy, who come in at age seventeen or eighteen; often in first year classes they weren’t quite sure why they were there at all, but then some would go on to become honors students in philosophy. In America I was teaching law students or graduate students who had already done a first degree, and I was teaching small optional seminars: so the students were very committed to the enterprise, they volunteered for the class; and the students were much more advanced, more certain of what they were doing and why they were doing it. (They were also paying much more money, and thus more concerned about getting something back for it. I found the American students very impressive in their commitment to the law; some of them were doing a lot of interesting pro bono work outside the classroom. With undergraduate students, it was more a matter of helping them to find their intellectual feet. The best, the most pleasing students to teach were those who came in rather uncertain, not very clever, not very bright, and you saw them over three or four years becoming more certain and more confident, and getting a decent degree. There we could feel that we did make some difference. That was very exciting. Very good students would do it anyway, regardless of us; the very bad students, whom we couldn’t engage, they were our failures; but with the students whom we could see improving, and whom we could believe we were in certain ways helping—that’s the exciting part of teaching.

Marshall: We taught in a philosophy department, we didn’t have a great many PhD students, so we were primarily teaching courses with undergraduate students. Undergraduate students come to university pretty much at 18 years old, though some could be a bit younger, 17 maybe or occasionally 16. At any rate, they all come to philosophy without having done any philosophy at all, so teaching philosophy is different from teaching mathematics or history where they have experience of these subjects. We were always in one sense dealing with a tabula rasa (this is may also be true for law, of course). Many students come to the subject having no idea about it at all. Also, because of the structure of the degree programs in our university, most of the students in the first year would not necessarily be continuing to do a degree of philosophy, philosophy was just one subject among many, so in teaching you have to be aware of the fact that you should not be speaking as if you were training up 250 professional philosophers. The aim is to enable everyone to get something out of doing a philosophy course, recognizing that this is not going be the most important thing in their lives. Actually, I think it’s a really important thing for any teacher in the university to understand: philosophy might mean everything in the world to you, but it would be a big mistake and quite wrong to assume that it has that status for everyone you are teaching; but you have to enable them to come to an understanding and to getting something out of it, to see something worthwhile in what they are learning. So it doesn’t mean you mustn’t have high expectations of them, but just to limit those expectations, and to make sure that they are reasonable. And I think our experience has been in fact that even though many students are not going on to do something specifically in philosophy, for a good number of them, I’d say, doing some philosophy did make a difference. Not long ago we met someone quite accidentally, on a train, who came up and said “Remember me? I was in your philosophy class as a first year student”. I think she had become a school teacher, and she said “it was one of the most interesting things I did in my first year”. And I was pleased by that: it helped her in some ways and she enjoyed it, and I think that’s as much as you should demand. Αthough I have to say, students don’t always years later remember your classes for what you would necessarily expect them to remember it for; sometimes, not always, they remember it, not for your fine lectures, but for quite incidental things. I remember a student once who came and said: “The philosophy class I did was one of the most interesting things, I will never forget the lectures in the first year”. Now, the class she never forgot was one of the classes on a course on moral philosophy and moral theory, and we discussed the case of shipwrecked sailors eating the cabin boy, the famous case of Dudley and Stephens. She said: “I’ve never forgotten that”. I think she practically forgot everything about moral theory but she never forgot discussing cannibalism.

Kioupis: What would you advise a young student who wants to study criminal law and later perhaps philosophy of criminal law? Another perhaps naive question. Would you advise him to read one specific book, which is essential? Any other helpful advice? What made you, you as a person, decide to study and to work in this field for many years?

Duff: I don’t believe in the one book theory

Kioupis: I don’t believe either, but I had to ask.

Duff: Personally I came very to it very gradually: while I was a student in Oxford, I went to some seminars given by H.L.A. Hart and Rupert Cross, and they seemed rather interesting. I enjoyed talking about the cases, they seemed quite fun; and then I kept on reading bits of law here and there and I enjoyed reading cases—I often found it easier reading cases than reading philosophy books. So there was only a gradual drifting into law: there was no epiphany, no road to Damascus, no one book which said … I never studied law…

Papageorgiou: You know that Hart never studied law either!

Duff: To a student I would say, read some cases, read some real law before you start reading these theories: it’s important to engage with law as it is, and the cases are important. And then, I couldn’t say you should read this or that one book, but I would certainly think about the cases, read a few articles, and find what engages you critically; think critically about the cases. People find different ways in: I would just say, read rather widely, and that means reading articles or books, and find what engages you and can help you to start thinking for yourself.

Marshall: Well, I don’t want to try to correct your memory of your own philosophical development but, as I recall, when you first came to Stirling you were teaching moral philosophy, philosophy of action, and an influential book would have been Anscombe's Intention. If you think about law and intention it is in criminal law cases in particular that you see these actual philosophical ideas and notions having a life and functioning in what is really the most fascinating of institutions.

Duff: That’s true … It was purely by chance that in the 1970’s I worked on philosophy of action, and also at that time the English Law Commission released some reports on criminal law, and on the role of intention and things like that: that seemed very interesting, so I wrote some articles on those issues, trying to bring philosophy to bear on legal thinking. But it was purely by chance that I happened to read these reports, and they seemed to connect with what I was doing; so again it was a fortuitous career…

Papageorgiou: A slightly different question. I was reading “Crime and punishment” again. “Crime and punishment” is so full of theories. Second half of 19thcentury human psyche, crime, punishment, all the socialist theories in Russia about society and the human psyche about religion and about crime and about punishment ... Do you think works of art that have to do with crime and punishment whether they are … a trove of interesting moral insights about the phenomenon you have been studying philosophically?)

Duff: yes!

Marshall: I would say that it is impossible to do moral philosophy if you don’t read novels. That is where you find moral life, and Crime and Punishment should for a moral philosopher really just be one of the basics. I think it’s very influential.

Papageorgiou: So, back to Rascolnicoff then …

Marshall: But don’t forget Plato and Aristotle, without Plato and Aristotle, we philosophers are just a footnote.

Duff: I also think it’s very important for those doing any kind of legal theory that they don’t become too specialized. Part of what’s changed in the last forty years or so is that there’s more connection between legal theory and philosophy and sociology: there’s much more interconnection between disciplines, so that if you’re going to do law you must also do philosophy, and vice versa. This kind of breaking down of barriers between disciplines is very important: that’s part of what has changed in the last 40 years—more intertwining of disciplines, more mutual engagement.

Tzannetaki: As we come to the closure of this very stimulating discussion I'd like to read to you a short quote from Prof. Duff which would allow us to conclude in an optimistic tone with regard to the prospects of communicative punishment. "Once", writes Prof. Duff, "we grasp the fact that the criminal justice system is less a monolithic and unitary institution than a set of diverse and partly autonomous sub- systems, we will also see that there may be room, in some contexts, for at least modest efforts at a communicative penalty. "This minimalist version of communicative punishment is, I believe, realistic here and now in specific local contexts where the preconditions of communicative punishment already exist or can easily be secured. Such a small scale, selective application of ideas, practices and values may then have the potential to spread further with time. Isn't this also the recent history of restorative justice?

Duff: Yes, I’m torn. There’s the grand theory side of things—a theory of criminal law in all its coherent structured glory, the Platonic form of criminal: but we have to ask whether we can try to make any of that actual. On the one hand, we can in some small ways try to make punishment work like this. At the same time, however, this takes us back to the matter of preconditions: if we think that the preconditions of punishment are radically lacking, then it’s not clear what we can partially do without first addressing the pre-conditions, before we try to reform punishment.

Tzannetaki: Perhaps at a very local level… you could have the pre-conditions…

Duff: Maybe, yes, I hope that’s true. If I take the large view it would be very pessimistic: you see the horrors of the system, and the horrors are salient. But you’re right that if you look more locally it is more likely that in a particular area, in a particular court or a particular set of probation officers, they are doing that kind of work. We shouldn’t forget that possibility—that in that way we could find the beginnings of …

Tzannetaki: And then it gradually expands… that’s the optimistic scenario……

Duff: Except there’s one more thing: that an important dimension needs to be the two way process of communication. It’s not just that we must communicate somehow with the offender, that they are called to answer to us: we must also answer to them, they must be able to challenge us; and that isn’t very prominent even in those locally productive, hopeful areas—it’s still a bit one-way. We demand an answer from the wrongdoers: but they must be able to stand up and say “But don’t forget how we’ve been treated, don’t forget what you owe to us”. I think it’s important to emphasize that answering is a two-way process: you answer to me, and I answer to you. If we could see that in these more local areas, then that would really be hopeful.

Kioupis: When is your next book about to be published?

Α. Duff & S. Marshal: This year ... in May…

Kioupis: It’s almost ready… What’s it about?

Duff: I get the proofs this month. It’s called “The realm of criminal law”, and began for a project we did on criminalization. We thought we would produce a theory of criminalization: here are the principles that should guide decisions about criminalization. That was our ambition, but of course we failed to do that. So then I began to think more seriously about what role criminal law should play in a political community: I give an account of criminal law, and of a particular kind of political community, and of the “civil order” of such a community; and I show how criminal law serves both to sustain and to constitute that order. This is meant to make more sense of the idea of crimes as public wrongs: it’s really an attempt to make clearer, and to develop in more detail, the kind of account we’ve been working on for some years. When I started the book, I thought that this would be the definitive account: this will be it! But of course: it’s one more effort to make things a bit clearer, and there’s plenty of work left to do.

Marshall: Thank God! There’s work to be done…

Kioupis: Thanks Konstantinos for inviting professor Duff and professor Marshall…

Duff: Thank you it’s been a really enjoyable discussion… We really enjoyed the discussion on Thursday in the legal philosophy seminar. The questions and comments were very insightful we thought and very helpful; we really enjoyed ourselves.

Kioupis: Recently I have had the chance to read some of your articles... I discovered that you have written a book about criminal attempts… I am teaching general part of criminal law… I have now a task to read your book…

Marshall: … We just got started! There’s so much more to talk about!

Tzannetaki: This has been a communicative process, not simply an interview.

Papageorgiou: A communicative process… of a communicative theory!